Progress for 0 ad

Progress for 1 ad

Progress for 2 ad

Progress for 3 ad

Munir Shemsu

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Imagine a newly paved road in your neighborhood, replacing a dirt road with smooth asphalt. At first glance, it might just seem like another project, but behind it lies a massive investment of public funds. A month after its completion, you’re still getting used to the ease of travel when, one morning, you wake up to the sound of construction workers digging some parts of the road. The Addis Ababa Water & Sewerage Authority has begun installing new pipelines—something that wasn’t coordinated before the road was built.

As crucial as roads are to urban life, they are just one piece of a much larger infrastructure puzzle. Water, electricity, telecommunications, and other essential services must come together to create a fully functional city. But because there was no unified approach, the newly paved road had to be torn up.

And the roads are still not for everyone. The sidewalks remain inaccessible to the visually impaired, and the installation of tactile paving is necessary before the road truly serves all members of the community. The result? Disintegrated efforts, frictions, half-met ambitions, and excluded communities because key factors were not considered.

Digital systems face a similar challenge. A standalone digital platform is like that asphalt road: useful but incomplete on its own. If digital systems are fragmented, they risk leaving people behind. If they lack interoperability, they become inefficient.

Picture having a National Digital ID, yet the transport bureau refuses to recognize it as proof of identity. Or being forced to open a new bank account simply because a service provider only accepts payments through one specific institution. These inefficiencies create exclusion and, at the very least, unnecessary friction hindering adoption.

Without a broader viewpoint, digital systems risk trapping people in even more bureaucratic red tape, especially when there is low digital literacy and weak data-sharing practices. The challenge becomes even greater when viewed through a geographic angle. If urban residents struggle to access services due to confined technologies that aren’t built on an integrated national infrastructure, the situation is undoubtedly more daunting in rural areas. The ability of different regional bureaus to share data has profound implications for end users in an increasingly digital economy. The consequences of inaccessibility are particularly severe when it comes to payments, taxes, or health services.

Thus, it becomes fundamental to question whether a hyper-localized roll-out of technology in a few urban areas contributes to hindering mass adoption without a robust, reliable substructure. Trust in new technology is also intimately tied to first impressions, especially when it concerns people’s finances. How successful can national targets to increase digital financial access be without a foundational infrastructure that’s scalable, interoperable, and inclusive?

Even though most stakeholders and advocates of digitization state the necessity of a physical network and energy infrastructure to spur the adoption of technology in emerging economies, only a handful point to the nuances of what infrastructure means in the digital age.

As the pace of digital evolution rapidly accelerates, reevaluating existing standards, design principles, legal frameworks, and standards of engagement become increasingly paramount. Digital infrastructure no longer only means physical objects like the number of cell phone towers or the proximity to power stations; it also includes software platforms, service standards, e-signatures, interoperable designs, and application programming interfaces (APIs). Concepts of privacy, digital identity, personal data, and digital regulatory frameworks require imminent reassessments through a digital lens for inclusive impact.

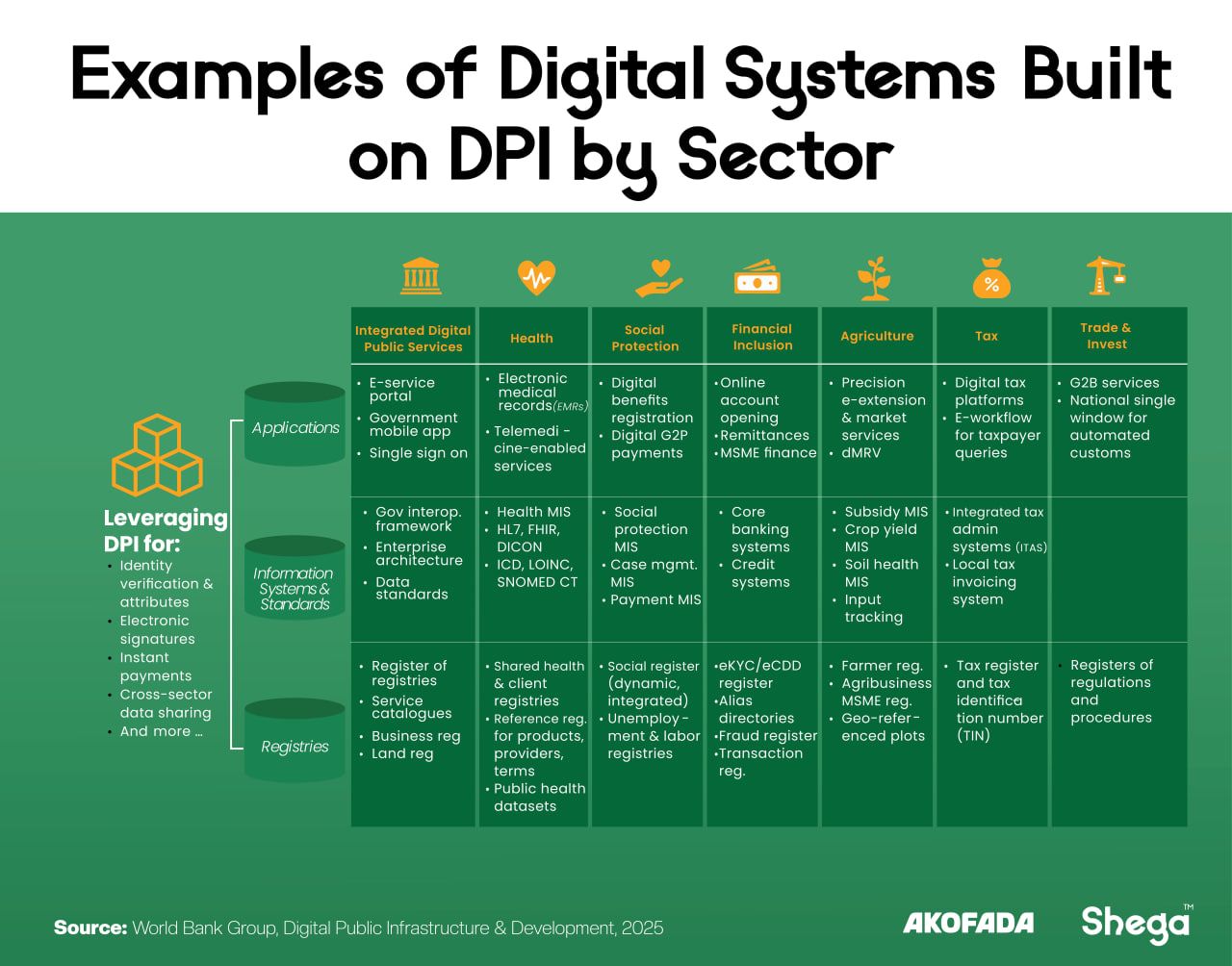

Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) is a new term that emerged in the public sphere, following the G-20's recent consensus on its definition. The description of DPI that was collectively adopted by the group is: “a set of shared digital systems that should be secure and interoperable, built on open standards, and promote access to services for all, with governance and community as core components.”

The World Bank Group (WBG) further complements this definition by describing DPI as foundational digital building blocks for public benefit. Key features of DPI, according to the WBG, include interoperability, openness, minimalism, and modularity—the ability to separate and recombine system components. DPIs focus on reusable, horizontal foundations, signaling a shift away from traditional digitalization approaches that, in many cases, have led to fragmentation and silos.

Themes of openness, inclusivity, and user-centricity are common across most definitions, with digital identity, payments, data sharing, and core government data registries frequently cited as critical components. Examples of DPI include India's Aadhaar system for digital identity, UPI for payments, and the India Stack data exchange framework, as well as Estonia’s X-Road, an open-source government data exchange system.

Despite slight variations in the finer details of DPI definitions, there is broad agreement on their implications, especially for developing economies. Of course, this excludes those few perennial skeptics who harbor reservations about any form of digitization, increased integration, or the expansion of technology.

In the manner that the mass production of cars necessitated standards for road construction and design, and rules of engagement for drivers, the same needs to be followed for technology developed for public use.

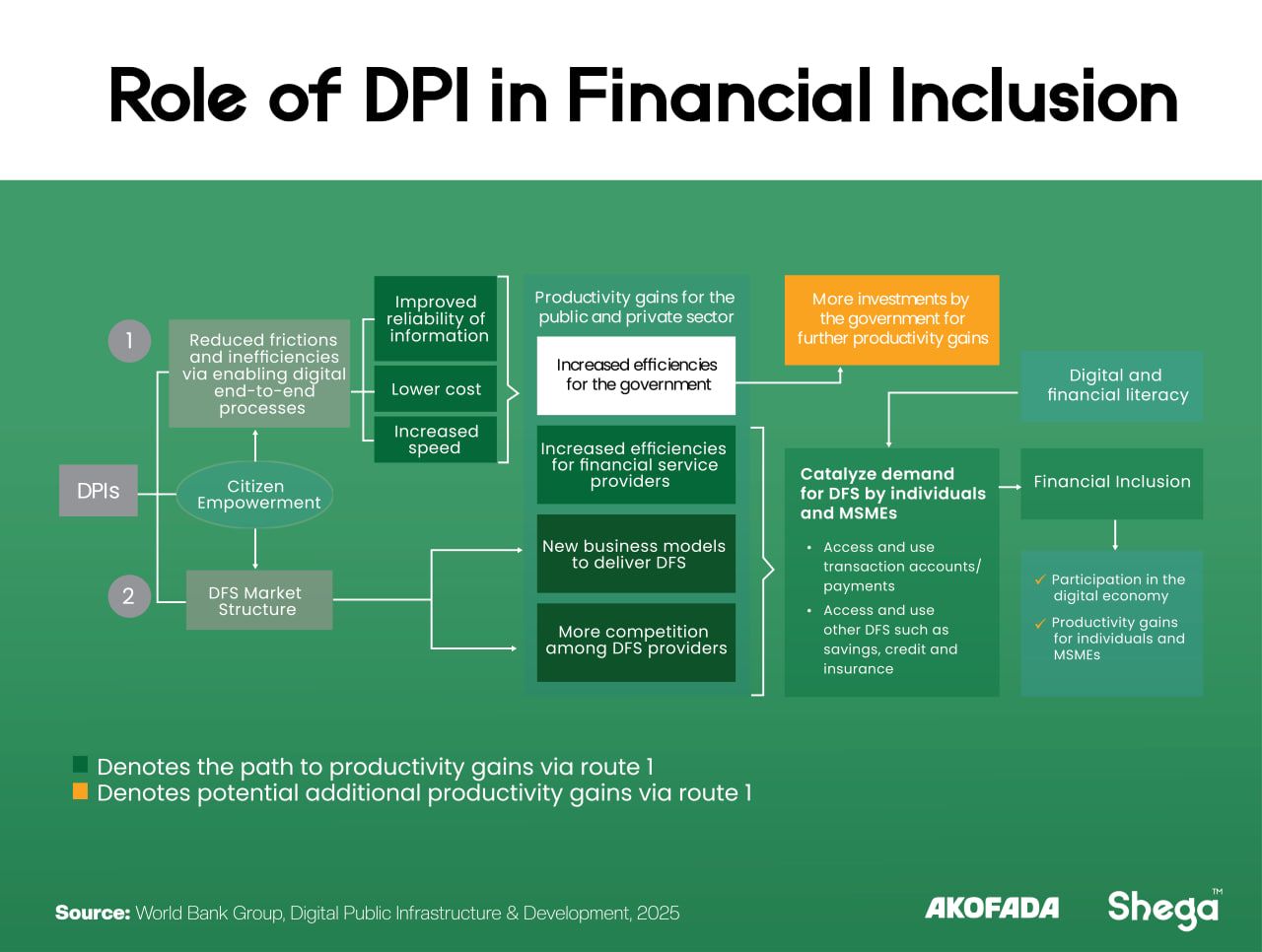

Furthermore, the understanding and development of DPIs are bound to influence the pace and effectiveness of digital financial inclusion, technology adoption, the speed of innovation, pricing models for technology providers, and even governance. A shared infrastructure built upon DFI core principles also lays the groundwork for regional cooperation between countries.

From DPI’s broad spectrum of foundational capabilities, identification is widely considered among priorities of the highest order. Similarly, Ethiopia has a relatively well-developed DPI in this regard. Fayda, a national ID project, looks to register around 90 million citizens. The 12-digit, uniquely identifying number buttressed by biometric data (iris scans and fingerprints) is issued to all eligible residents under the ambitious initiative.

Ethiopia’s Prime Minister has repeatedly underscored the importance of the project to realizing national targets in taxation, financial inclusion, and security. He told Parliament last year that Fayda represented the second-most important national project taken by his administration, preceded only by the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam in importance.

The Fayda project, which gained momentum following a parliamentary green light of the digital ID proclamation in 2023, has registered a little over 13.5 million people currently while eyeing 70 million for the year. Around 52 agencies have been integrated with the program, spearheaded by the PM office, and supported by development partners like the WBG and local commercial banks. The advances have been particularly evident in the capital, Addis Ababa, with everything from a new bank account to tax payments requiring national IDs as a precondition. However, this mandatory requirement for accessing government services has also raised concerns about exclusion.

While Ethiopia’s foundational identity objectives are marching along steadily, other concerns about a legislative backdrop that ensures transparency, personal data protection, and purpose limitation also remain pertinent. For a country with less than six months of experience operating under a fresh piece of personal data protection legislation, tailoring implementation for local administrative levels remains elusive.

A recent paper on digital IDs in East Africa warns of stifled opposition voices and state critics without adequate legal safeguards around the use of data. Furthermore, the lack of robust data security guardrails could invite predatory actors in a country with a relatively underdeveloped cybersecurity infrastructure like Ethiopia. Despite the nexus of challenges, the Fayda project laying down foundational pillars for identity, remains by far the most significant stride in DPI development in Ethiopia.

As Ethiopia prepares to embark on another five-year national digital strategy, perhaps the only other major advancement in national DPI establishment is the infrastructure deployed by the country’s national switch operator, Ethswitch. Operating as a share company that comprises nearly all financial service providers in the country, and spearheaded by the National Bank of Ethiopia, Ethswitch’s initiatives meet several standard features of DPIs.

The national switch operator marking 11 years of operation has had a particularly profound impact in advancing interoperability between financial institutions. Ethswitch enabled nearly 123.2 billion birr worth of interoperable ATM transactions during the last financial year and around 270 billion birr in P2P transfers.

However, it remains behind some continental economic peers in terms of inclusivity, as most transactions are circumscribed to the capital and a few other urban centers. Responsive redress mechanisms, clear limits on transferable amounts, real-time settlement through multiple options, and transparency also endure as areas requiring further growth.

In November of last year, EthSwitch introduced a National Payment Gateway, a product meant to serve as the bedrock of online payments in Ethiopia. The gateway enables customers to make fast, secure, and convenient online payments using various channels and payment methods, such as debit cards, bank accounts, wallets, QR codes, and aliases (phone numbers).

As EthSwitch is the national switch operator, no financial player is excluded. The payment gateway’s use is open to all banks, microfinance institutions, mobile money service providers, and payment processors.

Ethiopia’s interoperable QR payment standard is another part of the nation’s effort to establish a unified and efficient national payment infrastructure. The standard means customers can scan and pay at shops, regardless of their bank or mobile wallet provider. Previously, QR Code transactions were confined to specific bank accounts or wallets, resulting in a fragmented system and hindering wider adoption. Though implementation is lagging behind, the National Bank of Ethiopia has mandated that all payment service providers adopt the Standard for Interoperable QR Code Payments.

Other relatively nascent efforts by the Ethiopian government to develop DPIs include the public key infrastructure (PKI), which enables encrypted third-party verification for digital certificates and electronic verification, the movable collateral registry by the central bank, and a few other digital registries in agriculture and title deeds.

Still, data silos in the public sector, underdeveloped communication channels between regional states, and premature legal frameworks, assail these endeavors.

In August of 2022, the United Nations released a report that warned of increasing encroachments to digital privacy and sovereignty by state and corporate actors. Following a global shock in the wake of revelations about the Pegasus software, which infiltrated journalists, foreign governments, and human rights activists, the Report resurfaces debates around encryption. Now bolstered by artificial intelligence, enriched datasets from data-heavy "smart city" initiatives, and evolving trends within social media platforms, tools designed to serve communities risk becoming instruments of exploitation. An active recognition of these risks should always contour the development of DPIs.

One key concept that has emerged intimately tied to DPIs has to do with the Digital Public Goods Standard (DPGS). The Standard, formulated per the UN Secretary-General’s aspirations for digital cooperation, establishes the baseline requirements that must be met in order to earn recognition as a digital public good (DPG).

Adherence to sustainable development goals, platform independence, respect for applicable privacy laws, and best practice standards are among the key indicators. Openness is a central theme to the DPG objective, with even the Standards being open to contribution on GitHub. DPG status is granted just for a single year, allowing the latest insights from technological developments to be incorporated into the evolving set of standards. Around 192 DPGs have been registered thus far, providing a mix of open-source software, public platforms, data, and portals across the globe.

In Ethiopia, the absence of a robust DPI is particularly impactful in the app development sector for financial services. The lack of transparency in transfer fees, unclear limits on daily transfers, and isolated integration of services within a specific set of companies are evident. Compounded by the dearth of identification, there is also a lack of variability in the set of financial services available through digital tools. Digital insurance services, investment facilities, and tailored tools for farmers are effectively absent. Even though digital financial services have expanded significantly, with 4.1 million digital credit accounts in the last financial year, the lack of disaggregated public data limits the insights that can be extracted for spurring financial inclusion. Furthermore, an aversion to open APIs often ends up stifling innovation from developers operating outside the umbrella of incumbent operators.

Despite consensus on DPI being a recent development, some regard the internet and Global Positioning System (GPS) as early forms of DPI. While the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET), a research project under the US Defense Department, laid down the precursor to the internet in the early 1970s, few can successfully argue that the US military created the Internet. Millions of people over subsequent decades experimenting with ideas in a largely open-source space continue to invent the internet. Businesses, governments, individuals, and development actors, nudged by a diverse set of motives, agree to operate under specific protocols to continuously develop the world’s first DPI.

Naturally, current debates about ownership of the internet are just as pertinent when thinking about the next wave of DPIs. Identifying areas better left to state actors or private businesses could have major consequences in terms of outcomes. For instance, the United States Department of Education’s decision to assign debt collection responsibilities to private sector operators like Mohela led to lawsuits and aggrieved students. While countries like India have experienced unprecedented success in state-led, multi-layer DPI development. Aadhar, a digital identification system, the Unified Payments Interface (UPI), and the Account Aggregator data exchange framework—among other services—have collectively transformed millions of lives in India.

Ethiopia’s recently unveiled digital agriculture roadmap looks to emulate India’s success. If successful, the plans to build a digital stack fitted with APIs, an interoperable data set, and consent mechanisms will be highly consequential for more than 15 million agricultural households in the country. Together with the Fayda national ID and Ethswitch’s payment infrastructure, the scaffolding for impactful DPIs and DPGs could be underway. Complementing these efforts by nurturing robust legal safeguards for data privacy, creating secure data-sharing channels, and adopting an open-source mindset just might be the closest thing to a panacea.

This article is an output of AKOFADA (Advancing Knowledge on Financial Accessibility and DFS Adoption), a project working to increase knowledge and transparency within Ethiopia’s DFS ecosystem.

👏

😂

❤️

😲

😠

Munir Shemsu

Munir S. Mohammed is a journalist, writer, and researcher based in Ethiopia. He has a background in Economics and his interest's span technology, education, finance, and capital markets. Munir is currently the Editor-in-Chief at Shega Media and a contributor to the Shega Insights team.

Your Email Address Will Not Be Published. Required Fields Are Marked *