Progress for 0 ad

Progress for 1 ad

Progress for 2 ad

Progress for 3 ad

When business payments are masked as personal transfers, it becomes harder for policymakers and financial institutions to recognize the real scale of commercial activity. It distorts economic indicators, stunts the development of tailored financial products for small businesses, and ultimately slows down efforts to build a more inclusive digital economy.

What appears today as a statistical oversight could soon turn into a structural problem and a missed opportunity to formalize, finance, and grow the very businesses driving Ethiopia’s digital transformation.

I live on the 9th floor of a condominium that has no elevator. Before you start feeling bad for me, the building actually has 18 floors, and several people have made these higher levels their home.

To be honest, life here is not particularly difficult. Going out and returning just requires a bit more planning because you do not want to forget anything important. Moreover, the delivery service from a small shop on the ground floor has made life convenient. For just 20 birr per order, I can have items delivered right to my doorstep.

This win-win situation, where I enjoy convenience and a hardworking individual earns well-deserved money, has been going on for almost a year now. Throughout this time, I would estimate that 95 percent of my payments have been made digitally.

This means hundreds of low-value, frequent digital payments amounting to thousands of birr. However, all these transactions were made to the shop owner's personal bank account. These payments, along with millions of others made by Ethiopians, are aggregated and reported as transactions between two individuals (peer-to-peer (P2P) transactions) in quarterly and annual reports.

I often find this a major challenge, as do many people working in or interested in the digital financial services (DFS) sector. Despite the fact that people are clearly making payments online for products and services daily, a reality we all witness, these figures can’t be mapped in digital transaction reports.

Similarly, countless small businesses have taken over social media, selling their products through platforms like TikTok and Telegram. In these informal markets, as well, transactions mostly happen online, and yet, these money flows mostly happen in P2P channels.

Are these invisible business transactions over P2P channels a missed opportunity for Ethiopia? Could they grow into a major problem? The answer is a clear YES.

When business payments are masked as personal transfers, it becomes harder for policymakers and financial institutions to recognize the real scale of commercial activity. It distorts economic indicators, stunts the development of tailored financial products for small businesses, and ultimately slows down efforts to build a more inclusive digital economy.

With a projected nominal GDP of $117 billion in 2025, making it the second-largest economy in East Africa, and over 2.5 million registered businesses, it would be wise to ask where these transactions are happening and what it takes to finally bring them to light.

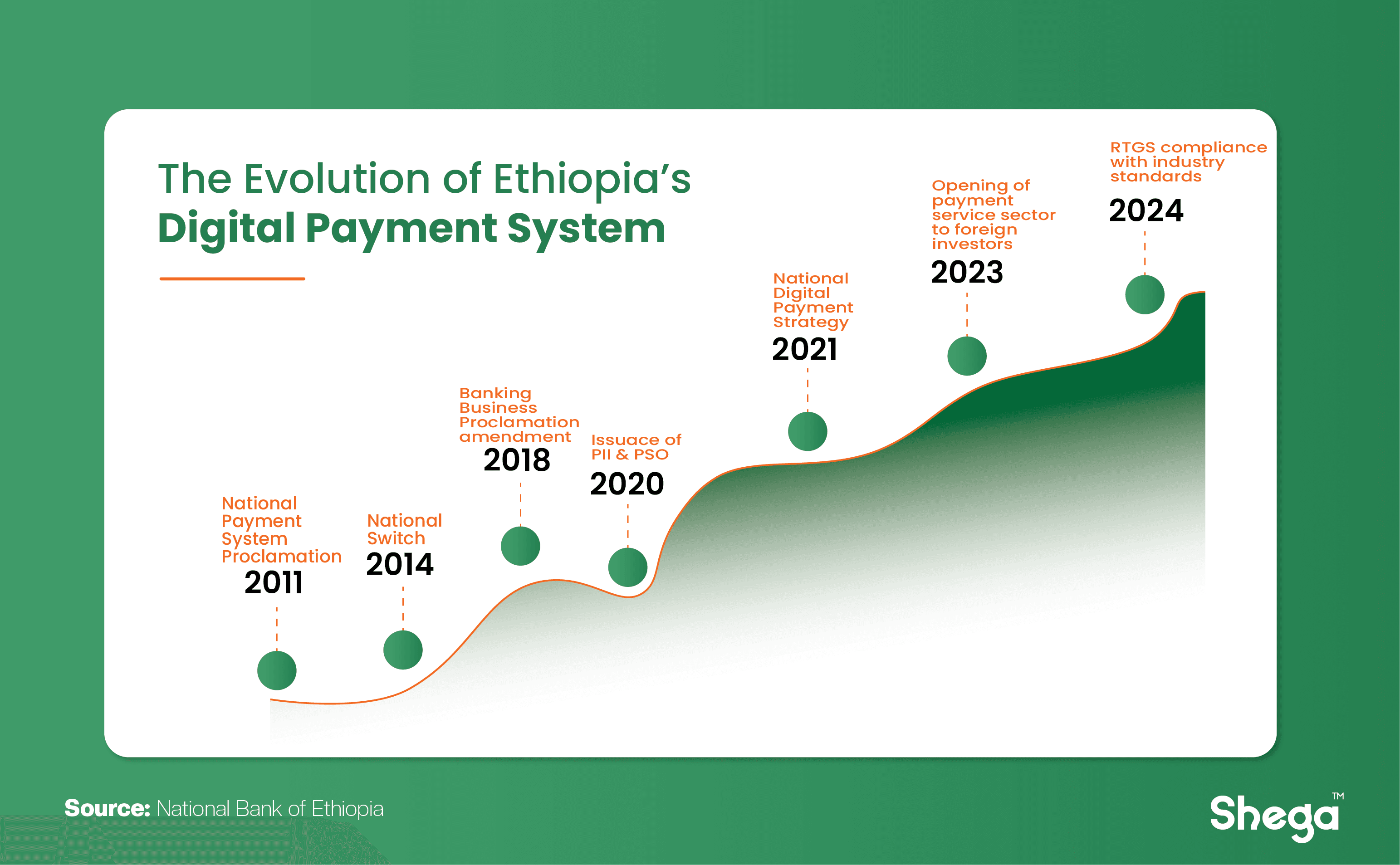

Ethiopia’s shift toward digital payments has been a decade-long journey marked by deliberate policy, infrastructure, and regulatory reforms. It began with the 2011 National Payment System Proclamation, which legally recognized electronic payments, followed by the launch of the Ethiopian Automated Transfer System (EATS), enabling real-time interbank settlements.

In 2014, the creation of the National Switch enhanced interoperability across payment channels. The 2019 amendment to the Banking Business Proclamation welcomed non-bank DFS providers, with licensing directives introduced in 2020. The National Digital Payments Strategy (2021–2024) elevated digital payments as a national priority, and in 2023–2024, legal reforms allowed foreign investment in the sector.

The country’s commitment to modern financial infrastructure is paying off. A new report by the Center for Financial Inclusion at Accion, while ranking Addis Ababa lowest among five global cities, highlights a growing trend of digital adoption among small businesses in the city. The report, which surveyed over 800 enterprises in Ethiopia’s capital, found that 49% of them reported using digital tools, with 11% of respondents indicating they used more than one platform.

Similarly, a report by Visa titled “Value of Acceptance: Understanding the Digital Payment Landscape in Ethiopia” provides further insight into the rapid uptake of digital payments among Ethiopian Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). The study surveyed SME owners and managers across various sectors and business sizes.

While 43% of SMEs still express a preference for cash, over 80% of surveyed businesses have adopted digital payments within the last two years. Furthermore, 64% of these SMEs plan to invest further in digital payment technologies, signaling strong confidence.

This trend is clearly mirrored in the country’s transaction figures. At the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia, the nation’s largest bank, digital channels now account for 80% of all transactions. The number of digital accounts across various platforms grew to over 200 million nationwide in the past fiscal year, while digital transactions reached 9.7 trillion birr, representing a 129% increase.

But how many of these transactions are payments for goods and services? The data remains vague. What is currently available are aggregated figures for transaction types such as ATM withdrawals, mobile banking, internet banking, agent banking, point-of-sale (PoS) transactions, and mobile wallet transfers. A significant portion of business transactions, like the one between me and the shop owner, are buried within these categories, often masquerading as simple mobile banking and wallet transfers.

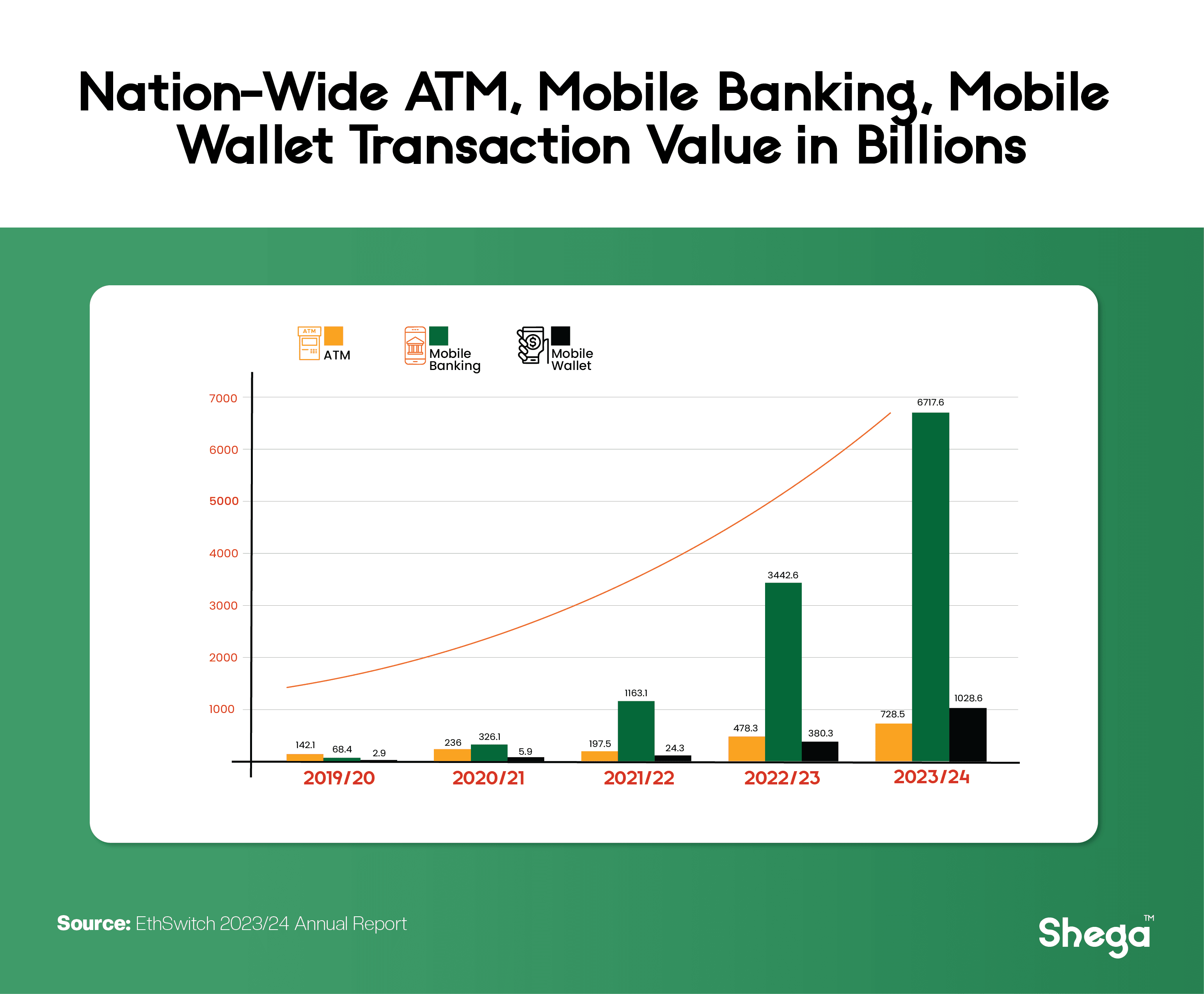

Data from the National Bank of Ethiopia shows that mobile banking transactions saw nearly 10,000% growth between 2019 and 2024. By the end of the last fiscal year, 1.1 billion mobile banking transactions had been recorded, totaling 6.7 trillion birr in value.

EthSwitch, the national switch operator, has played a major role in this expansion, steadily enhancing interoperability for P2P transfers. In fact, in the 2023/24 fiscal year, interoperable P2P transaction volumes surpassed interoperable ATM transactions for the first time.

Mobile money has followed a similarly explosive trajectory. Between 2019 and 2024, the value of mobile money transactions surged by 34,631%. By the end of the most recent fiscal year, 764.88 million mobile money transactions were conducted, amounting to a total value of 1.03 trillion birr.

Unlike other digital transaction types, PoS transactions—usually conducted directly between consumers and businesses—can be more clearly classified as payments. In the 2023/24 fiscal year, 10 million PoS transactions took place nationwide, amounting to 24.2 billion birr.

Other clearly identifiable digital payments include fuel purchases, which totaled 170 billion birr in the first nine months of this fiscal year, transactions through online payment gateways, and person-to-government (P2G) payments such as utility bills, taxes, and fines. Ethiopia is also increasingly leveraging electronic transfers for its social assistance programs, further highlighting the growing role of e-payments in the country’s financial ecosystem.

However, beyond these categories, digital payments in Ethiopia remain largely unidentifiable. This is a serious concern. What appears today as statistical oversight could evolve into a structural weakness. As digital finance expands, better visibility into what counts as payment is essential, not just for regulators and policymakers but also for the businesses and individuals building the country’s digital economy.

When digital payments occur over P2P channels, the payee or the customer loses several important rights and protections that would otherwise be available in a formal business transaction (B2B or B2C).

Ethiopia’s Electronic Transaction Proclamation (2020) established key provisions for e-commerce, including legal recognition of electronic receipts and digital communications as valid evidence. Though implementation still lags behind, the framework was designed to enhance consumer protection in digital commerce, particularly in cases of disputes, fraud, or faulty service delivery.

When customers pay businesses through personal P2P channels, they do not receive formal e-receipts. These digital receipts, which can only be generated by registered merchant accounts, serve as verifiable proof of purchase and are essential for dispute resolution, warranty claims, and returns. Without them, consumers have no official record that a transaction was tied to a commercial exchange.

This lack of protection and transparency in digital transactions erodes customer confidence in digital commerce overall. If consumers repeatedly face poor service, undelivered goods, or scam transactions without the ability to seek recourse, they may revert to cash-based or in-person purchases

In addition, in a mature payment ecosystem, reward arrangements, loyalty points, and targeted offers are built around business transactions. Ethiopian customers who pay over P2P channels miss out on these added values, which could otherwise incentivize repeat purchases, offer cashback, or help track personal spending.

In theory, using digital payments would allow businesses to track sales accurately, improve cash flow management, and accumulate a financial history that unlocks credit. However, this potential is lost if all transactions are lumped under P2P transfers.

Operating primarily through P2P payments restricts small businesses’ ability to access loans, insurance, and other tailored financial products. Because these transactions are recorded as personal transfers, they do not generate the kind of financial statements or categorized cash-flow data that banks and other financial institutions require to evaluate a business or its credit score.

One Ethiopian vendor told Shega that he readily takes small loans from a mobile money service when short on cash, highlighting how these loans are viewed as personal emergency credit, not structured business financing. Indeed, the current digital credit offerings in Ethiopia are mostly personal micro-loans rather than SME-oriented credit lines. The overall result is a vicious cycle: lacking formal records keeps businesses informal and credit-starved, which in turn prevents growth that would encourage formalization.

DFS providers can’t serve what they can’t see. P2P payments typically record only the sender, receiver, and amount – they do not capture merchant category, purpose of payment, or product details. At best, they might see periodic cash deposits or transfers into a formal account, but not the granular detail of daily sales.

This means DFS providers lose data on cash flow stability, peak sales periods, customer base size, and overall turnover of these businesses. Such data could have been used to offer collateral-free loans, overdraft facilities, or cross-sell services (like insurance or asset financing). Instead, the service providers must treat these entrepreneurs as if they have patchy or nonexistent financial activity.

The prevalence of business-through-P2P transactions doesn’t just affect individual firms and banks – it has macro-level implications for Ethiopia’s economic development and financial inclusion goals.

When commercial transactions go unregistered as such, it enables underreporting of income and sales. Ethiopia already struggles with a low tax base – the tax-to-GDP ratio fell to about 11% in 2021 (from 19% in 2002), one of the lowest in Africa. Widespread informal trading (including digital informality) is one of the key drivers of this gap. P2P payments make it feasible for a shop to have a significant turnover that never shows up in income tax filings.

In addition, accurate data is the bedrock of effective policy design. If policymakers cannot gauge the true level of MSME activity, it becomes harder to design targeted support programs. The lack of visibility into transactions could lead to underestimating their contribution and needs. As a result, programs for SME development might be under-resourced or misaligned.

Furthermore, unrecorded business transactions contribute to the underestimation of the digital economy’s scale and the exclusion of critical data that inform national indicators such as GDP and employment statistics, ultimately distorting economic analysis and policy responses.

ATMs are automatically excluded when discussing digital payments for goods and services. Meanwhile, despite their strategic positioning, PoS devices have either become a technology that Ethiopia has leapfrogged or one that the country has yet to fully embrace.

The number of PoS devices in Ethiopia grew only modestly, from 9,780 in 2020 to 14,030 in 2024. This figure lags significantly behind continental peers. For comparison, Nigeria had deployed 3.04 million PoS machines as of July 2024.

In Nigeria, fintech companies focusing on business services have made substantial progress, with some even achieving unicorn status. Moniepoint, which identifies itself as Nigeria's largest merchant acquirer, serves over 10 million businesses and individuals in Nigeria, processing over 800 million monthly transactions.

Ethiopia’s ascent to these numbers won’t be any time soon, if ever. Therefore, efforts to increase digital payments should prioritize strengthening existing use cases and strongholds. Specifically, the focus should shift toward converting current peer-to-peer mobile banking and wallet transactions into merchant-based payments.

Efficiency and cost-effectiveness are among the key justifications cited by the Ethiopian government in its push to transform the country into a cash-lite society.

There is no doubt that shifting from cash to digital payments results in significant long-term savings for governments. However, the same cannot be said for DFS users in Ethiopia. Ethiopians have recently been grappling with additional costs on digital transactions, including a 15% VAT.

While this is a broader issue that warrants a deeper policy discussion, regulators and DFS providers should at least implement lower transaction fees for merchant payments.

Globally, merchant account fees are generally higher due to added services such as fraud protection, chargeback handling, detailed reporting, and multi-currency processing. For example, credit card processing fees typically range from 1.5% to 3.5% per transaction

However, Ethiopia has compelling reasons to diverge from global norms. In a context where users are increasingly price-sensitive when it comes to transaction fees, lowering fees for merchant accounts could serve as a strong incentive. This could encourage both businesses and consumers to adopt merchant channels over peer-to-peer alternatives.

Imposing cash limits and creating tax incentives for electronic taxable transactions are among the key recommendations outlined in Ethiopia's National Digital Payment Strategy to promote the adoption of digital payments.

Unsurprisingly, the latter—tax incentives—has been the most overlooked. Conflicting national priorities are pushing businesses away from using merchant accounts and creating barriers to future adoption.

Ethiopia’s recent $3.4 billion Extended Credit Facility arrangement with the IMF includes provisions for increased revenue mobilization, which has translated into a heavier tax burden on businesses. The government is already seeing results. The Ministry of Revenue collected 649 billion birr in the first nine months of the current fiscal year, marking a 74 percent increase.

However, many traders report that they are struggling to keep up with the mounting tax pressures. Some business owners, particularly small retailers, have already reverted to informal trading because they fear the formal system may ultimately overwhelm them. A number of reported tax complications and unfair assessments stem from tax officials automatically labeling P2P transactions made to business owners’ personal accounts as business income.

In this environment, the benefits of Ethiopia’s digital payment initiatives, like the recently rolled out standardized QR codes are likely to face widespread resistance.

Introducing tax incentives for electronic taxable transactions, such as reduced tax rates or tax refunds for digitally traceable payments, could encourage formalization and adoption. This could also help in reducing the size of the shadow economy over time.

In the early years of mobile money, Kenyan merchants widely accepted payments through personal M-Pesa accounts, creating similar challenges to those now seen in Ethiopia. In response, Safaricom launched Lipa na M-Pesa, a merchant-focused solution offering registered tills, business dashboards, and access to financial products like Boost Na Biashara, a credit facility designed specifically for small enterprises. Today, Lipa na M-Pesa transactions constitute a substantial and growing share of Kenya’s digital payments.

Similarly, merchant accounts should not just be payment tools in Ethiopia, they should be gateways to broader financial inclusion. By integrating payments, financial history, and lending into a single merchant ecosystem, DFS providers can create a self-reinforcing loop of formalization. Businesses start transacting more transparently, build verifiable financial records, and gradually qualify for more sophisticated products. Meanwhile, providers gain access to valuable data that can inform product development.

In this aspect, Ethiopia faces another structural hurdle: a very high degree of economic informality, with most SMEs operating without formal business licenses or tax registration. Expecting these businesses to acquire a business license just to open a merchant account is unrealistic.

But formalization does not always have to start with government registration. DFS providers can take the lead, crafting merchant onboarding pathways that reflect the informal realities of Ethiopian commerce. This means decoupling merchant account creation from formal business registration and offering simplified, digital options for unregistered traders.

For example, Ethio telecom could introduce a lightweight merchant account tier within telebirr that requires only basic personal identification. Over time, this data could form the foundation for customized financial products, such as working capital loans. This loan offering could later be tied to a business license requirement to increase credit limits.

A few months ago, the Merchant Payments Ecosystem Observatory was launched in Ethiopia, a collaborative effort led by FSD Ethiopia and DFS Lab, with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. This long-term initiative is designed to systematically track, analyze, and support the growth of digital payments among merchants across the country.

By producing nationally representative data, the Observatory aims to offer a clear lens into merchant behavior, digital payment adoption trends, and the untapped opportunities for broader financial inclusion.

This kind of data-driven approach is not just timely, it is critical. As digital transactions continue to surge, Ethiopia risks not only losing visibility into its digital payments ecosystem but also forfeiting the many economic and financial benefits that come with it.

If business transactions continue to take place over P2P channels, the country will entrench into a digital economy that will be difficult to fully grasp, support, and grow.

The path forward lies in building merchant accounts that are accessible, low-cost, and fully integrated with financial services. These accounts are not just payment tools; they are the critical bridge between informal digital commerce and a truly inclusive, data-driven financial ecosystem.

Without this bridge, Ethiopia’s digital economy will continue to grow, albeit in the dark.

This article is an output of AKOFADA (Advancing Knowledge on Financial Accessibility and DFS Adoption), a project working to increase knowledge and transparency within Ethiopia’s DFS ecosystem.

👏

😂

❤️

😲

😠

Kaleab Girma

Kaleab Girma, an Addis Ababa-based reporter and researcher, with over six years of experience in the field. He currently serves as Shega's Editor-in-Chief and specializes in reporting on small businesses, innovation, technology, and startups in Ethiopia.

Your Email Address Will Not Be Published. Required Fields Are Marked *