Progress for 0 ad

Progress for 1 ad

Progress for 2 ad

Progress for 3 ad

Etenat Awol

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Financial inclusion has been a national agenda and a key priority in Ethiopia for some time, with much of the effort focused on mobile money as a tool to bridge the gap. In recent years, this focus has led to the opening of millions of mobile money accounts, offering encouraging signs that the financial inclusion gap may be starting to narrow.

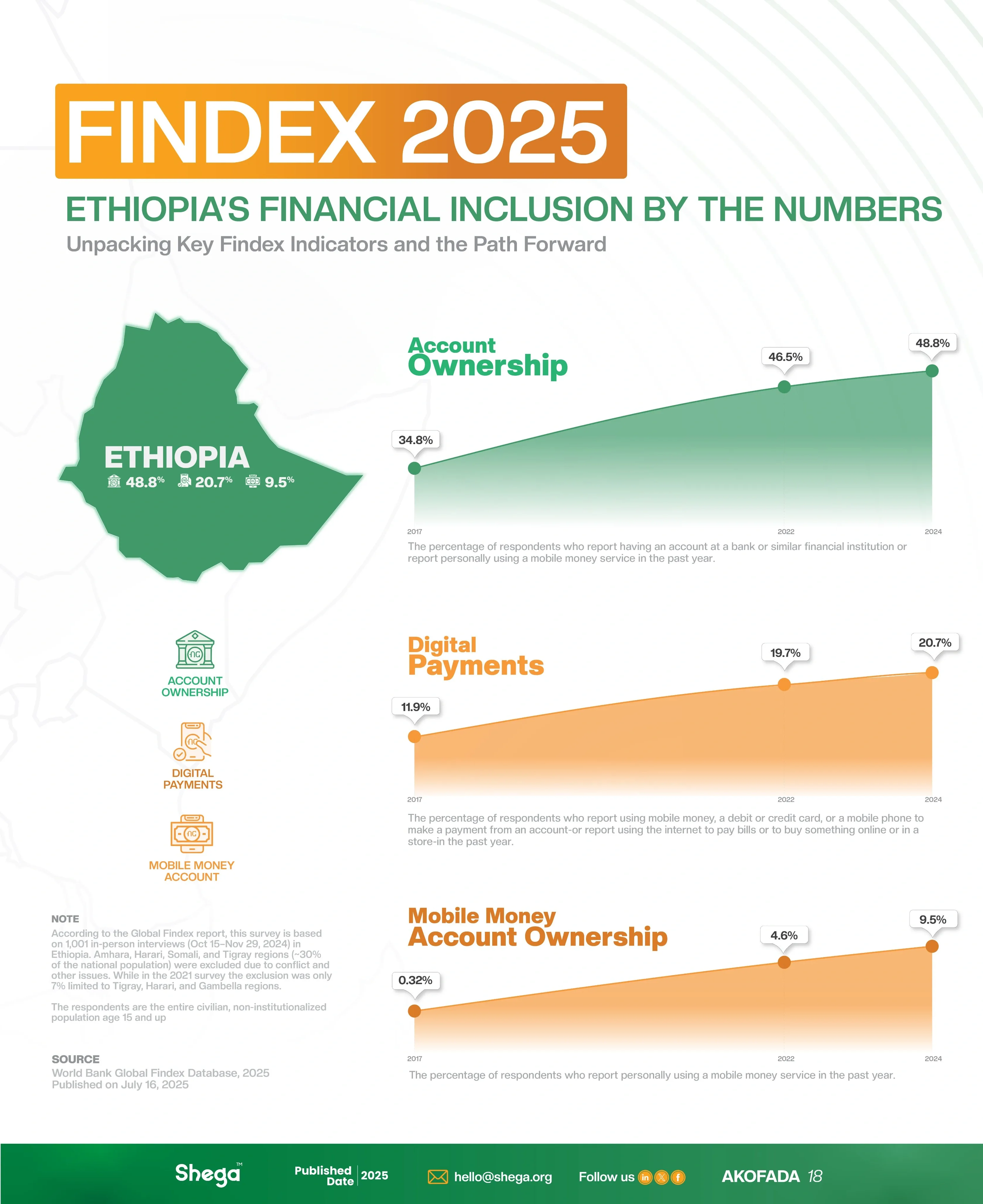

Yet, the latest 2025 Global Findex reveals that only 49 percent of Ethiopian adults own an account. Financial literacy, limited smartphone access, and physical distance still exclude millions from digital tools that many in urban areas now take for granted.

Ethiopia’s digital finance journey is undeniably one of progress, of platforms built, systems launched, and new habits formed. But it is also a story of persistent gaps. Gaps between who gets to participate and who gets left out. Between what the technology promises and what the infrastructure delivers. Between counting accounts and achieving meaningful inclusion.

This article is an output of AKOFADA (Advancing Knowledge on Financial Accessibility and DFS Adoption), a project working to increase knowledge and transparency within Ethiopia’s DFS ecosystem.

For the past three years, Ethiopia’s financial inclusion data has been primarily sourced from the Findex 2022 report, a widely recognized database on how adults across the globe access and use financial services. The Global Findex, launched by the World Bank in 2011, is based on nationally representative surveys involving around 145,000 adults across 141 economies, covering over 97% of the world’s adult population. It is an essential resource for anyone tracking trends in financial technology.

In Ethiopia, local stakeholders and several organizations such as the UNCDF have relied on the 2022 Findex data, which found that only 46% of Ethiopians had a bank account. This figure has been used in reports, studies, and speeches to convey key messages and support program launches. The National Bank of Ethiopia also relied on this data, more importantly, using it in the country’s National Financial Inclusion Strategy to evaluate the landscape at that time and define future goals.

Despite its importance, Ethiopian researchers and policymakers have faced a challenge in recent years. There was a strong belief that the 2022 report reflected a period that no longer aligns with current developments. Since then, the country has undergone rapid changes in digital financial services. As of June 2022, there were 94.7 million digital accounts in Ethiopia. By March 2025, these figures had surged to 222.1 million.

There was a growing sense that Ethiopia was closing the financial inclusion gap. However, the key question remained: by how much? Figures released by the National Bank and other institutions mostly indicated the number of accounts, without revealing how many individuals actually owned them or how many were actively used. Because of this, many in the field sought to place these numbers in the right context when referencing financial inclusion.

When the news broke last week that Findex would release its latest figures, anticipation was high. Many in the sector were eager to see whether the data would reflect the transformative digital shift Ethiopia had undergone. The 2025 Global Findex Database was released on Wednesday.

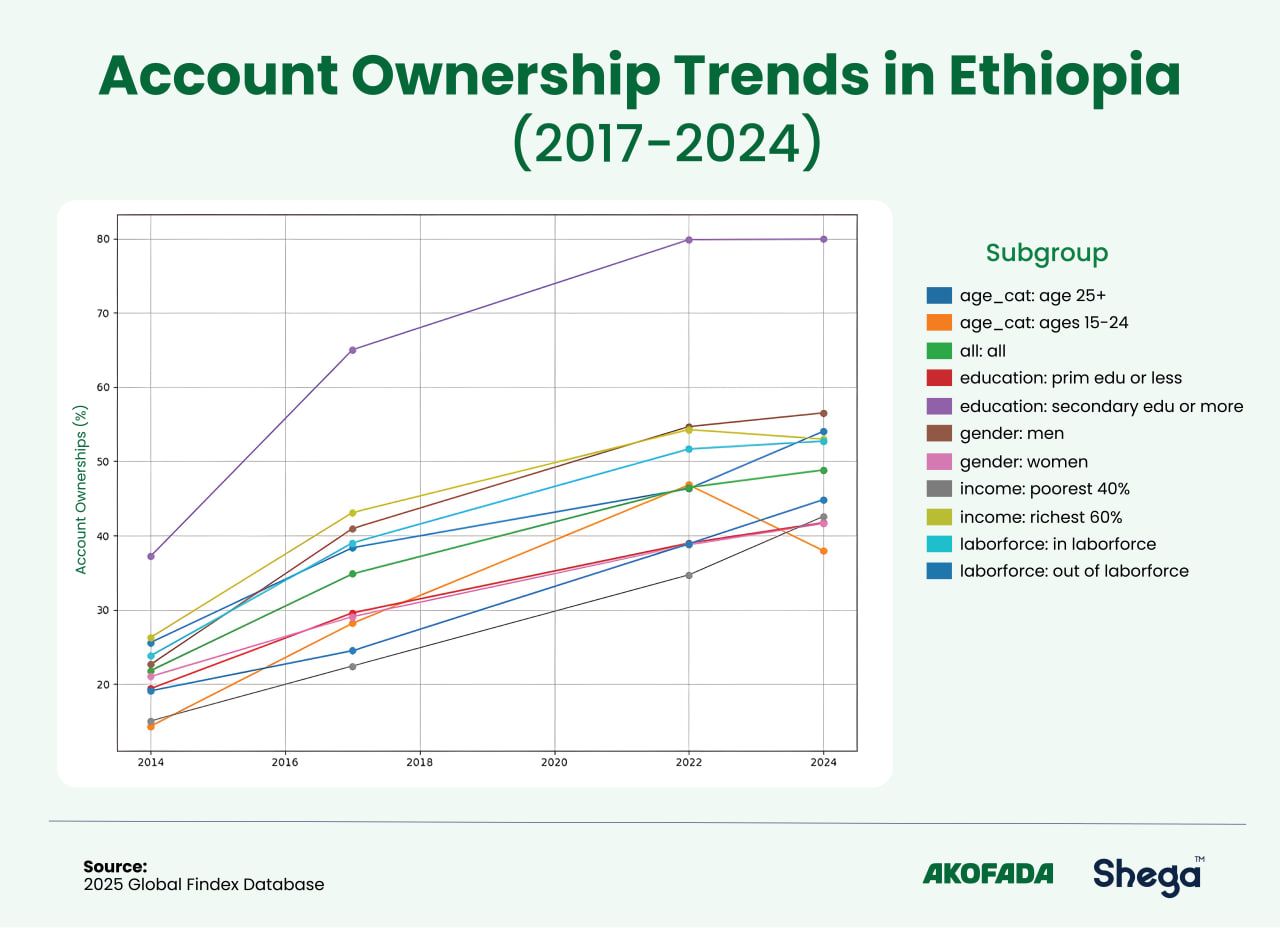

However, the figures are a far cry from the transformative change many had hoped. The report showed that account ownership in Ethiopia had only increased slightly, from 46% in 2021 to 49% in 2024. While the overall rise from 22% in 2011 to 49% today is significant, the pace has clearly slowed, and millions of Ethiopians still remain financially excluded.

The 2025 edition, based on surveys conducted the prior year, reveals a continued upward trajectory with 79% of adults globally now owning a financial account, up from 74 % in 2021 and just 51 % in 2011. In low- and middle-income countries, account ownership rose from 69% in 2021 to 75% in 2024. This year’s report also highlights an era in which nearly eight out of ten adults globally now have an account with a bank, another financial institution, or a regulated mobile money service.

In Ethiopia, the survey was conducted face-to-face with 1,001 adults between October 15 and November 29, 2024. The Amhara region, Tigray, Harari, and Somali regions were excluded from the survey due to a differing set of hurdles, according to the report. Despite these excluded regions collectively representing nearly 30% of Ethiopia's population, the report highlights considerable transformation in financial infrastructure, policy, and market dynamics

When the previous Findex database was published, only 46% of Ethiopian adults had a financial account. There was also a marked gender gap, with 56% of men owning accounts compared to only 36% of women. Mobile money accounts were at 4.7% and digital payments were used by fewer than one in four adults. While 45% of adults had mobile phones, the figures were six percent lower among the unbanked majority.

One of the most significant milestones over the past few years has been the rise in mobile money users in Ethiopia, with the number reaching 107.5 million as of June 2024.

At the beginning of this year, telebirr had reported reaching a massive customer base of around 54 million, a staggering rise from 21 million in its first year. Additionally, between September 2024 and February 2025 in just six months, Telebirr processed transactions totaling 1.01 trillion Birr, nearly matching the cumulative transaction volume of the previous three years.

Ethio Telecom has also expanded telebirr’s functionality beyond simple P2P transfers, adding features such as utility bill payments, government service fees, merchant payments, microloans, and even integration with diaspora remittance platforms.

The historic entry of Safaricom Ethiopia in 2022 is also another massive development that happened since the previous Findex Survey took place. Backed by a consortium that included Vodafone Group and Sumitomo Corporation, it was awarded the country’s first private telecom license for $850 million, the single largest foreign direct investment in Ethiopia’s history at the time. This marked the end of Ethio telecom’s monopoly and opened the door to more competition and innovation in both connectivity and mobile financial services.

Shortly after launching network services, Safaricom introduced M-PESA in Ethiopia in August 2023, after obtaining a mobile money license from the National Bank of Ethiopia, something unthinkable for foreign operators in the years prior. M-PESA’s entry brought with it over 15 years of operational experience from Kenya, instantly raising the competitive stakes in mobile money services. Safaricom is now averaging 30K new customers daily, while its subscriber base has grown to 10 million users.

Ethiopia’s regulatory openness has been partly guided over the past few years by the central bank’s National Digital Payments Strategy (2021-2024). As part of the broader Digital Ethiopia roadmap, it prioritizes financial inclusion, interoperability, infrastructure investment, and regulatory openness to non-bank actors.

And yet, despite all these advancements, around 39.9 million adults in Ethiopia still do not have an account. While millions of new mobile money accounts have been created in recent years, the Findex report suggests that this surge has had little impact on overall financial inclusion. The data implies that many of these accounts were opened by individuals who already had bank accounts, not by first-time account holders.

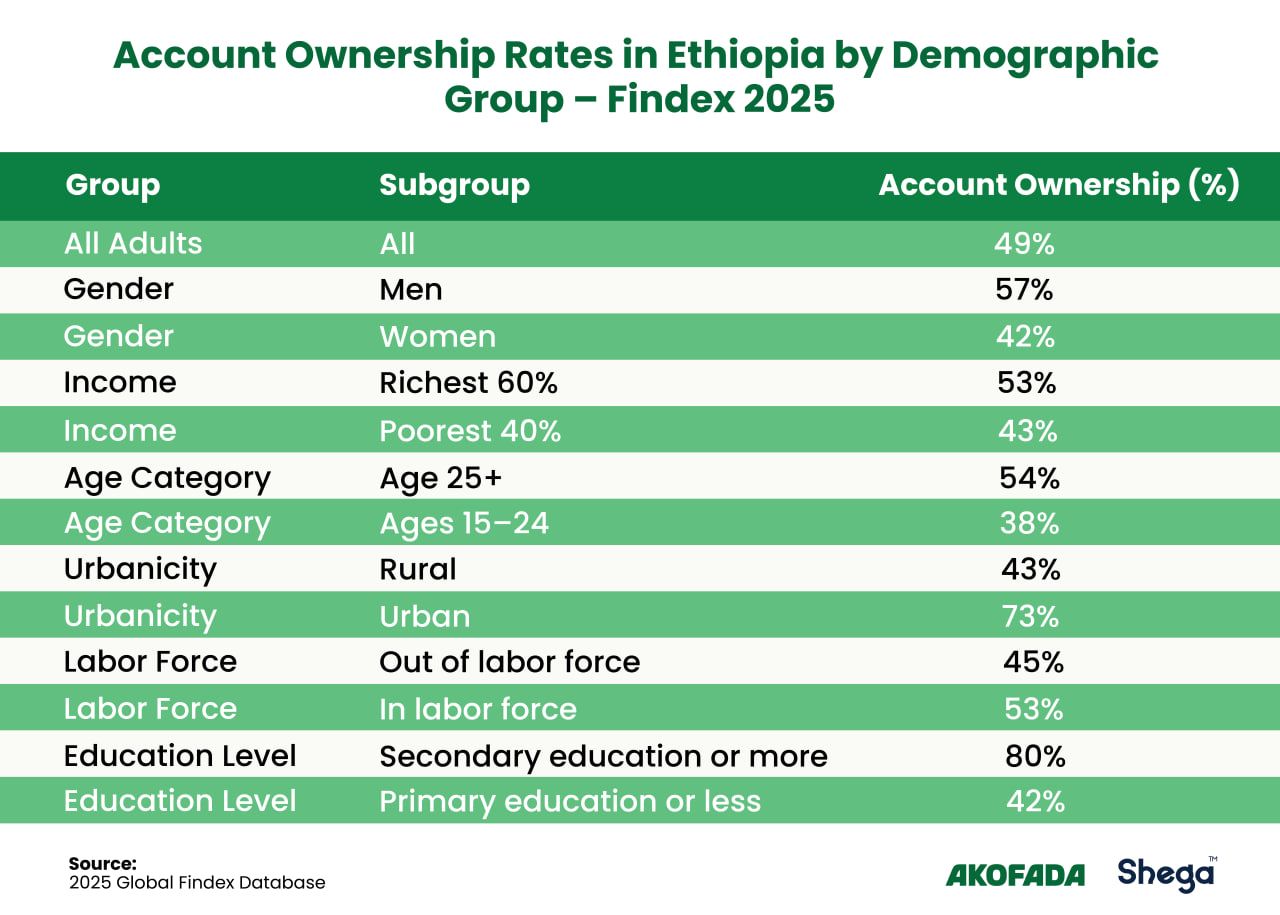

While the national increase in account ownership was modest, two population segments in Ethiopia saw more substantial gains in account ownership, reaching levels nearly on par with the global average for their respective groups. Among individuals with secondary education, account ownership reached 80%, while in urban areas, the figure stood at 73%.

At the other end of the spectrum, the divide remains stark for women, rural communities, and the poorest households. The reasons are all too familiar: not enough money to open or maintain an account, no nearby agent, or a lack of official ID (though this might be less of an issue going forward with the Fayda digital ID).

Nearly a third of adults do not use the internet, and basic mobile phones still dominate in many areas. Only about a third of Ethiopian adults used digital payments in 2024. While account ownership has grown slightly, meaningful use of digital financial services remains concentrated in urban centers.

Still, behind the modest growth in overall account ownership, there are signs of real change. Mobile money is quietly reshaping how people interact with financial services. Between 2021 and 2025, the share of adults with a mobile money account quadrupled from just 4.7% to 19.4%. More people are saving as well, up from 20.2% to nearly 30% and borrowing rose slightly as well. The number of adults using digital payments grew by over 12 percentage points, and more people are paying bills online or using cards. These shifts suggest that while formal banking may still be out of reach for many, digital tools are beginning to fill in the gaps.

Ethiopia still lags behind other countries in the region, like Kenya or Ghana, where mobile money is far more deeply woven into daily life. And while providers and platforms are in place, usage isn’t keeping pace. For many, digital finance remains something they’ve heard about but haven’t experienced, held back by deeper issues like affordability, lack of trust, and low awareness.

A critical aspect of understanding Ethiopia's digital and financial landscape also involves reconciling discrepancies between different data sources. A major variation exists between the Findex Database's demand-side, individual-level survey data and the supply-side, aggregate figures reported by telecommunication operators and government bodies.

According to internal National Bank data, Ethiopia’s overall financial inclusion rate is now between 62 and 64%, indicating faster momentum than demand-side data alone suggests. However, this is still short of the headline goal of the 2021 Financial Inclusion Strategy, which aims for 70% of adults to have a bank account by 2025.

This shows multiple data sources, such as the demand-side like Findex, and other bank and NBE side data, must be seen together, not in isolation.

Perhaps the more unsettling undercurrent in Ethiopia’s digital finance story isn’t the slow pace of growth, it’s who is being left behind. While urbanites increasingly navigate daily life through a latticework of mobile apps, QR codes, and digital wallets, the foundation beneath remains uneven, even brittle. The promise of inclusion has, so far, been delivered unevenly, with disparities evident in geography, education, and access. Adults with secondary education are nearly twice as likely to hold a financial account as those without. Distance alone is cited as the second most common barrier to account ownership. And in a country where digital finance is increasingly meant to be mobile-first, only 14% of surveyed adults reported using the internet in the past three months.

Even in cities, where infrastructure is strongest, the user experience is often patchy: platforms go down without notice, fees lack transparency, and offerings remain too generic to meet the complex financial lives of their users. Yes, Ethiopia has made undeniable gains. But has it built a system that listens, adapts, and evolves? Or one that celebrates scale while leaving depth behind? Insurance remains an unfamiliar concept to most. Credit, formal, affordable, and accessible, still eludes the vast majority. The path forward demands more than new platforms; it calls for deeper innovation, better regulation, and the political will to ask: inclusion for whom, and on whose terms?

Yet Ethiopia’s gains in financial inclusion cannot be disentangled from the country’s fraught political and economic backdrop. With an estimated 86 million people living in poverty, the highest number on the continent, progress is bound to be incremental. In addition, 45 percent of the Ethiopian population does not have access to electricity. Conflict, climate shocks and spiraling living costs continue to batter households already living on the brink, too many of whom earn less than a dollar a day, scarcely enough to justify, let alone sustain, a formal bank account.

In this context, a three-percentage-point rise in account ownership over three years may seem modest, but it may also be a mirror to the lived reality. For policymakers, the message is clear: progress will not come from scale alone. It requires the courage to confront uncomfortable questions, and double down on what works and rethink what clearly does not. The latest Findex report is yet another reminder that inclusion is not just about how many are counted, but about who is still missing and why.

👏

😂

❤️

😲

😠

Etenat Awol

Etenat holds a degree in Journalism and her master's in Public Relations. Previously, she served as a university lecturer and has five years of experience in communications, media, digital marketing, and consulting.

Your Email Address Will Not Be Published. Required Fields Are Marked *