Progress for 0 ad

Progress for 1 ad

Progress for 2 ad

Progress for 3 ad

Kaleab Girma

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

The central bank views digital lending as a tool to achieve basic financial inclusion at scale. Since 2022, when the first digital lending platform was launched in Ethiopia, more players have followed suit, and the country now has around a dozen such platforms.

However, shortcomings in transparency, credit limit policies, awareness campaigns, and borrower protection mechanisms are already emerging in this nascent sector, highlighting the need for robust, locally tailored digital lending laws.

This article is an output of AKOFADA (Advancing Knowledge on Financial Accessibility and DFS Adoption), a project working to increase knowledge and transparency within Ethiopia’s DFS ecosystem. Featured Image- Simon Maina/AFP/Getty Images

Ermiyas Assefa, whose name has been changed, is a colleague of mine. A few months ago, he took out a digital loan from telebirr, borrowing around 4,000 birr.

Unfortunately, he failed to repay it on time, and as daily penalties accrued, his debt kept growing. Ermiyas insists he never took the loan himself, claiming that a friend used his phone to borrow the money (sure, Ermiyas). At first, he ignored the reminder texts telebirr sent about the outstanding balance.

Then came the automated calls from telebirr’s 127 number. Still, Ermiyas didn’t budge. Maybe he truly hadn’t taken the loan and was waiting for his "friend" to settle the debt. Following these failed reminders, the situation changed. Instead of the usual dialing tone, he now heard an automated message reminding him to repay his loan when he made calls.

After some time passed Ermiyas finally repaid the loan, which increased to around 8000 birr due to the accumulated penalties. He states that he was unaware of the steps telebirr would take to collect the money before it happened, nor did he know the debt could increase by 100%. Each time something new occurred, he found himself in discovery mode.

Ermiyas is not alone. Unless you have defaulted on a digital loan, the only way to learn about the collection mechanisms used by digital lenders in Ethiopia is through others. Viral TikTok comedy skits, where borrowers share their experiences with collection calls and accrued penalties, have become a major source of information on digital loans.

However, educating the public about digital lending procedures and safe borrowing should not be left to loan defaulters. A lack of transparency is prevalent in the nation’s infant digital lending scene. An assessment of Ethiopia’s current digital lending sector also reveals shortcomings in credit limit policies, awareness campaigns, and borrower protection mechanisms, all of which require regulatory intervention and cooperation from digital lenders.

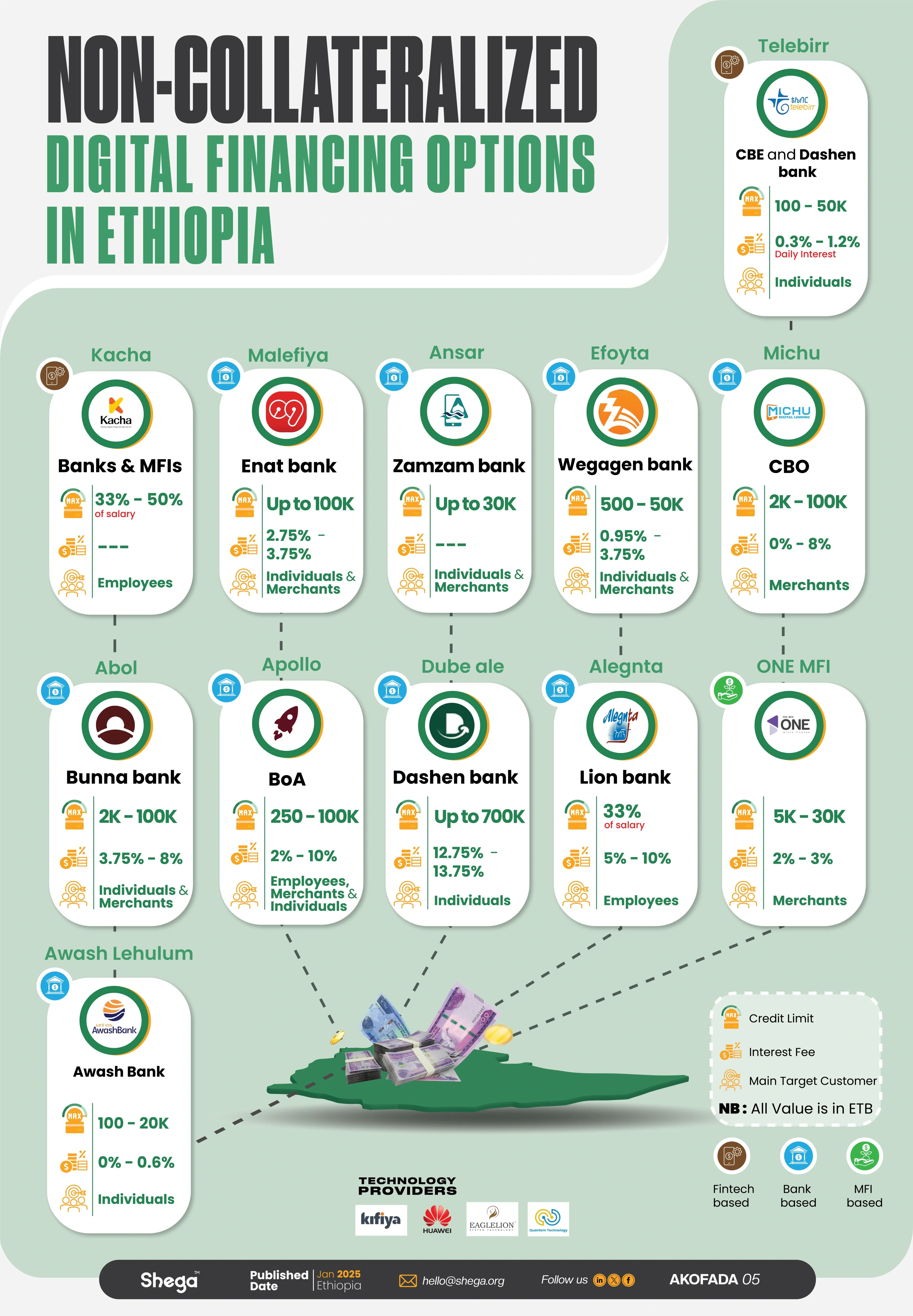

Though mainstreamed by telebirr, Ethiopia’s first digital lending product is Michu, a collaboration between the Cooperative Bank of Oromia (Coop) and Kifiya Financial Technology, launched in 2022. Michu was soon followed by telebirr. In the three years that followed, more players have entered the market, and Ethiopia now has around a dozen digital lending platforms.

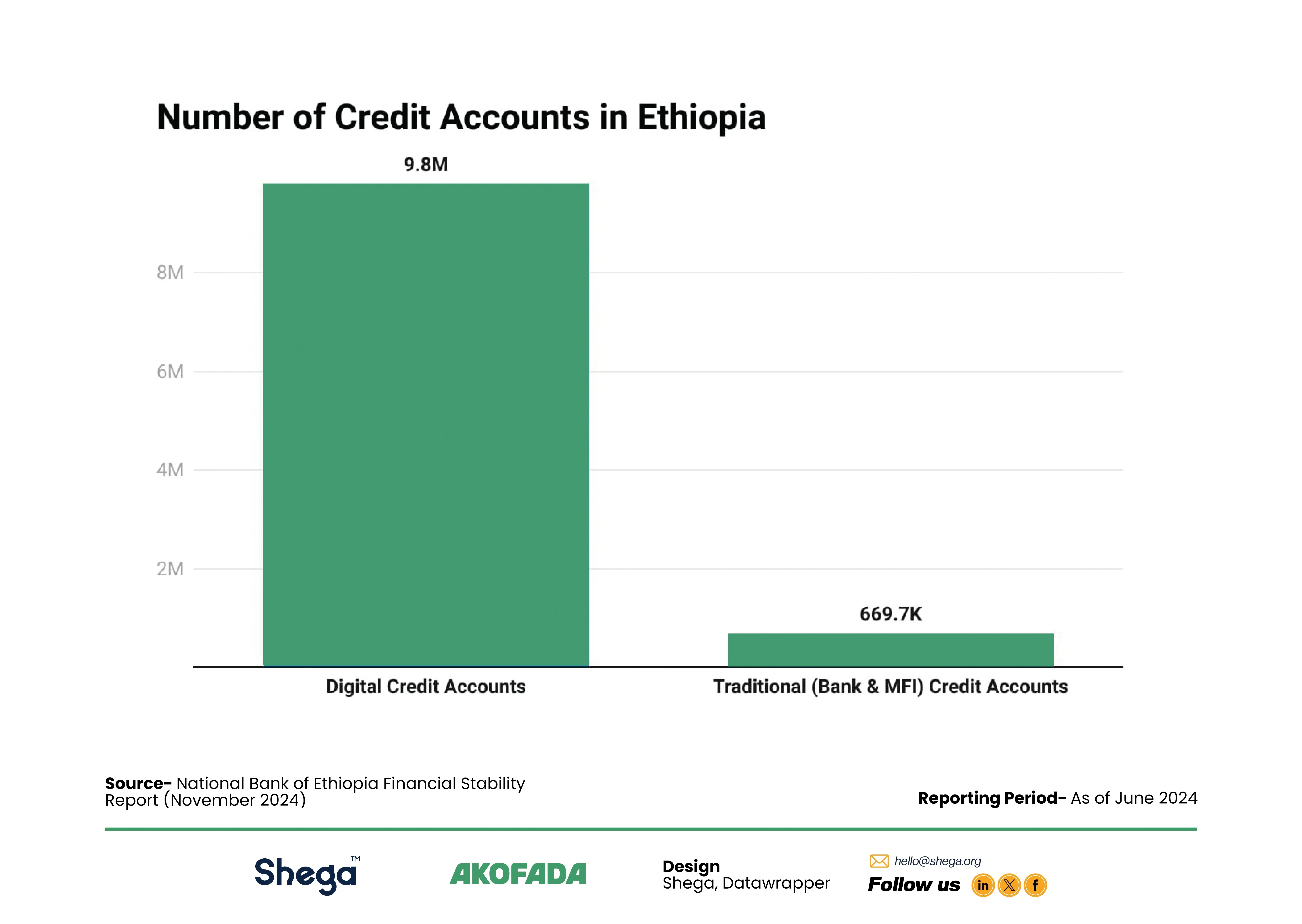

As of February 2025, Michu has reported providing over 16.5 billion birr in loans to one million MSMEs and individuals across Ethiopia. Meanwhile, telebirr through its partnership with Dashen Bank and the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia, has said it has disbursed 17.5 billion birr in loans to customers as of December 2024. And according to the National Bank of Ethiopia, there were 9.8 digital credit accounts in Ethiopia as of June 2024.

Until recently, Ethiopia’s regulatory framework for digital financial services followed a bank-led model, granting banks and microfinance institutions (MFIs) exclusive rights to provide financial services. This changed in 2020 when a legal amendment allowed non-financial institutions to enter the sector, including digital credit.

The Ethiopian government views digital lending as a tool to achieve basic financial inclusion at scale. The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) highlights this in its Financial Inclusion Strategy. One of the key priorities of the strategy is to create jobs and drive economic growth by reducing barriers to credit—particularly for MSMEs, women, and low-income households—while leveraging innovative business models.

With written approval from the central bank, financial institutions and licensed payment instrument issuers that have partnered with financial institutions can offer digital financial services such as micro-savings, micro-lending, and insurance.

However, the Licensing and Authorization of Payment Instrument Issuers Directive, which governs payment instrument issuers like telebirr, lacks specific regulations for digital lending. While the law permits digital lending and includes provisions covering various aspects of mobile money, such as e-money float management, account limits, and reporting requirements, digital credit is only briefly mentioned. It is listed as a permitted product and referenced only again in relation to the data mobile money issuers must report to the NBE quarterly.

Some customer protection rules in the directive may apply to digital lending, but they primarily regulate the user’s relationship with mobile money services as a whole rather than specifically addressing digital lending concerns.

At the end of 2022, a news report emerged that a draft law to establish a special licensing framework for digital credit issuers was in the pipeline. However, the law has yet to materialize.

Other countries have enacted specific laws to regulate digital lending. Some, like Kenya, introduced legislation reactively after an unregulated digital lending boom led to widespread issues that necessitated government intervention.

From the Philippines to India, Kenya, and Nigeria, predatory lending apps have surged in recent years. Before Kenya introduced an act to regulate digital lenders in 2021, anyone could easily run a digital lending company—no license was required. Simply registering the business was enough, and lenders had full autonomy over customer data. As with most unregulated markets, this led to chaos. The absence of oversight allowed digital lenders to impose exploitative interest rates and use debt-shaming tactics on borrowers.

Kenyan loan apps collect borrowers’ phone data, including contacts, and demand access to messages to check the history of mobile money transactions—for credit scoring and as conditions for disbursing loans. Rogue lenders then use some of the contact information collected to recover the loans disbursed in cases where borrowers default. Reports indicate that digital lenders resorted to debt-shaming tactics, like calling friends and family, to compel their borrowers to repay the loans.

Some companies also shared defaulters' data with third parties without consent. In response, Google has removed hundreds of loan apps from its Play Store in Kenya, following a policy change that requires digital lenders to submit proof of licensing.

In India, nearly half of the digital lending apps available between January and February 2021 were illegal, according to the country’s central bank. Many users have also reported cases of blackmail by digital lenders. In some instances, agents allegedly contacted borrowers’ acquaintances, harassed them, and even circulated altered obscene images of defaulters.

Of course, these are extreme cases, and drawing direct parallels to Ethiopia would be misleading. Ethiopia’s central bank maintains strict oversight of the financial sector, and digital lending is not an industry one can easily enter.

However, these examples highlight the need for robust, locally tailored regulations specific to digital lending. A well-structured framework should not only address existing gaps but also anticipate future challenges.

Take telebirr, for example. understanding the terms and conditions for the opening and use of telebirr lending services is not an easy task. Consider this excerpt from telebirr Mela (micro credit) service.

"If you repay your monthly credit within the due date, you will be charged a facilitation fee of 3% on day one, and you will be charged a daily fee ranging from 0.30% to 1.2% for the rest of the repayment period, depending on your credit limit."

This wording does not provide borrowers with clear and straightforward information about the actual cost of borrowing. What telebirr is essentially saying is that it charges a facilitation fee of 3% and a monthly interest rate ranging from 9% to 36%, depending on the user’s credit score. The agreement is phrased in the original way because interest is calculated daily, allowing the borrower to repay the loan before the 30-day due date. However, this factor can also be communicated effectively.

To clarify, telebirr could state: "You will be charged a monthly interest rate between 9% and 36% on your loan depending on your credit score. However, if you repay your loan before the due date, the interest will be calculated daily and you will pay a lower amount. An additional 3% facilitation fee is applied on loans, even if you repay early. Click here to find your credit score, interest rate, and how much you can save if you pay early".

Studies already show that digital lending platforms can make it harder for consumers to understand credit costs. When complex and ambiguous terms and conditions are added to the mix, borrowers may struggle to grasp the full consequences of their financial decisions.

A lack of transparency is also evident during loan application processes. On telebirr, when customers enter an amount to borrow, the platform does not display the interest rate. Instead, it only shows the total repayment amount on the due date and the facilitation fee. This lack of upfront disclosure limits borrowers' ability to make informed decisions.

Ensuring transparency in digital lending empowers consumers to compare loan options, understand repayment obligations, and choose between multiple service providers. Regulations should mandate clear disclosure of key details, including loan tenure, effective interest rates, fees, penalties, the recovery process, and other critical information. Additionally, digital credit providers should be required to present these terms in simple, accessible language that most target consumers can easily understand.

A 2022 demand-side diagnostic by First Consult estimates the financing needs of an MSME in Ethiopia to range between $1,500 and $26,000, depending on the size of the enterprise. Meanwhile, the total potential financing demand by MSMEs in Ethiopia is estimated to be around 9.6 billion dollars. Given this, it is essential to reassess the current digital credit limits set by lenders in Ethiopia.

Michu has raised its maximum credit limit, from its initial starting cap and currently sits at 100,000 birr. Telebirr, one of the earliest players, still maintains figures that are not that high from its initial threshold, 15,000 birr for individual borrowers. Meanwhile, Dashen Bank’s Dube Ale "Buy Now, Pay Later" product offers the highest credit limit, set at 700,000 Birr.

Most digital lending amounts in Ethiopia are designed for personal use and salaried employees, making it difficult to categorize them as targeted MSME financing based on their current limits.

Of course, scaling up quickly without considering existing usage patterns and success rates would be risky. However, even with this caution in mind, progress in raising credit limits has been slow, especially if financial inclusion truly means making credit accessible to MSMEs.

This is particularly notable when compared to the sweeping reforms taking place in the economy, including the financial sector. In April 2021, the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) raised the minimum capital requirement for commercial banks from two billion birr to five billion birr, with existing banks given until June 2026 to comply, while newly established banks were given an extended timeline.

Similarly, the central bank should take a proactive but measured approach in pushing for an increase in digital credit limits. Financial institutions as well as non-financial digital lenders already have access to extensive customer credit histories and financial data, allowing them to make more informed lending decisions

The push to increase credit limits should drive digital lenders to enhance their credit-scoring capabilities by investing in research, development, and innovation to strengthen their digital lending systems.

Without clear guidelines, digital lenders in Ethiopia rely on regulations designed for traditional banking to define non-performing loans (NPLs). Under existing rules, a loan becomes non-performing when interest and principal payments are overdue by more than 90 days. This timeline is designed and works well for conventional loan products, where payments are typically made monthly, meaning a borrower would have missed at most three payments.

However, applying this same 90-day period to digital lending is problematic, as penalties in digital credit are calculated daily. A 90-day NPL window for a one-month digital loan would result in charging interest and penalties for an additional 60 days, making the system more punitive. Therefore, establishing a more suitable timeframe for NPL classification in digital credit is essential.

Kenya’s Digital Credit Providers Regulation (2021) also sets a precedent by capping how much a digital lender can recover from a borrower once a loan becomes non-performing. Under this regulation, lenders can only reclaim the original unpaid loan amount, interest that does not exceed the unpaid principal, and reasonable recovery expenses.

Another critical regulatory gap in Ethiopia is the lack of a defined NPL threshold for digital lending portfolios. Currently, digital lenders must comply with banking rules, which require Ethiopian banks to keep NPLs below 5% of their total loan portfolio. While this approach ensures financial stability in traditional banking, digital lending carries higher risks due to the absence of collateral. International experience suggests that NPL ratios for digital loans tend to be much higher.

For instance, in Kenya, the number of loan defaulters surged to 7.74 million in October 2024, with borrowers blacklisted by various lenders, particularly mobile loan apps. This emphasizes the need for fitted regulations that reflect the unique risks and repayment structures of digital credit.

Have you ever tried taking a second loan on telebirr before repaying your first one? You can’t. This restriction is intentional and designed to prevent over-indebtedness. However, there is currently no mechanism in Ethiopia to prevent borrowers from taking multiple loans from different providers.

In Kenya, for example, some borrowers take out loans from more than five mobile lending apps simultaneously, often borrowing from one to repay another, creating a cycle of debt.

Consumer over-indebtedness poses a significant challenge to financial inclusion, financial stability, and consumer trust in the financial system. Addressing this requires strengthening Ethiopia’s credit reference framework to accommodate digital lending.

To mitigate the risks of over-indebtedness and enhance financial stability, Ethiopia must expand its credit reference system to include all financial service providers, including non-bank digital lenders.

Ethiopia’s Credit Reference Bureau (initially called the Credit Information Centre) was established in 2004 to address the challenges of obtaining adequate and timely credit information for assessing borrowers’ creditworthiness in the banking sector.

Initially, credit information was manually shared with lending banks, which were required to obtain borrower data from the Credit Information Centre before approving loans of 200,000 birr or more. The system was upgraded and expanded in 2012 and again in 2019, incorporating microfinance institutions (MFIs) and capital goods financing companies as subscribers, data providers, and users.

The expansion of the credit reporting system (CRS) has significantly improved loan portfolio management in the banking and MFI sectors. Aggregated and analyzed data provide insights such as borrower distribution, loan amounts, and patterns of repeat borrowing—key factors in assessing the financial sector's overall health.

The inclusion of digital lending to CRS requires real-time data sharing and fair access criteria for digital credit providers. Additionally, rules should be established to ensure responsible use of credit reference systems while balancing the potential downsides of negative listings for small-ticket loans.

Strengthening data collection on non-performing digital loans and conducting regular assessments of over-indebtedness, using specific parameters such as women and MSMEs, will also be essential in refining credit policies and closing financial inclusion gaps.

An experiment conducted on M-Pawa, a digital credit and savings product offered by Vodacom Tanzania and Commercial Bank of Africa (CBA) in 2018, highlights the benefits of increased understanding. Customers who engaged with learning content saw notable improvements: they increased their savings balances, took out larger loans, repaid their loans 5.5 days sooner, and made larger first repayments compared to customers who did not engage.

While many digital lenders in Ethiopia advertise their services, highlighting how easily borrowers can access funds with just a few clicks, few, if any, invest in educational campaigns that promote responsible borrowing.

Many borrowers in Ethiopia are unaware that digital lenders have the legal right to take defaulters to court—and have done so in a few cases. Young borrowers, in particular, may not fully grasp the long-term consequences of being blacklisted, including its impact on their future financial opportunities.

To address this gap, policies and programs should be implemented to promote digital financial literacy, especially among disadvantaged groups such as women and youth. Digital financial service providers should be required to run effective awareness campaigns and contribute to industry-wide financial education initiatives. These efforts must be transparent, ensuring that financial education programs are neither misleading nor biased. Furthermore, digital financial literacy policies should cover key areas such as risk awareness, consumer rights, and the complaint and redress process.

Lastly, policymakers should encourage productive lending over personal consumer loans, and consider allowing more digital lending providers, while ensuring oversight on pricing models.

👏

😂

❤️

😲

😠

Kaleab Girma

Kaleab Girma is a journalist and researcher with more than eight years of experience. He serves as Shega’s Media Manager, reporting on businesses, innovation, technology, and startups in Ethiopia.

Your Email Address Will Not Be Published. Required Fields Are Marked *