Progress for 0 ad

Progress for 1 ad

Progress for 2 ad

Progress for 3 ad

Munir Shemsu

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Caught between the old and new, MSMEs in Ethiopia are hindered by informality, vague definitions, and fractured finance. As digital financial services grow, true inclusion depends on building an ecosystem where digital tools meet informal grit, transforming overlooked entrepreneurs into powerful drivers of growth.

This article is an output of AKOFADA (Advancing Knowledge on Financial Accessibility and DFS Adoption), a project working to increase knowledge and transparency within Ethiopia’s DFS ecosystem. Featured Image- The Sudan Times

Upon receiving my monthly pay last month, I decided to visit the hotbed of commerce in our neighborhood, Mekanisa, Addis Ababa, for a few purchases. True to form, I haggled at nearly every outlet in the sprawling informal market to get a feel for the general price levels. Expensive was the verdict.

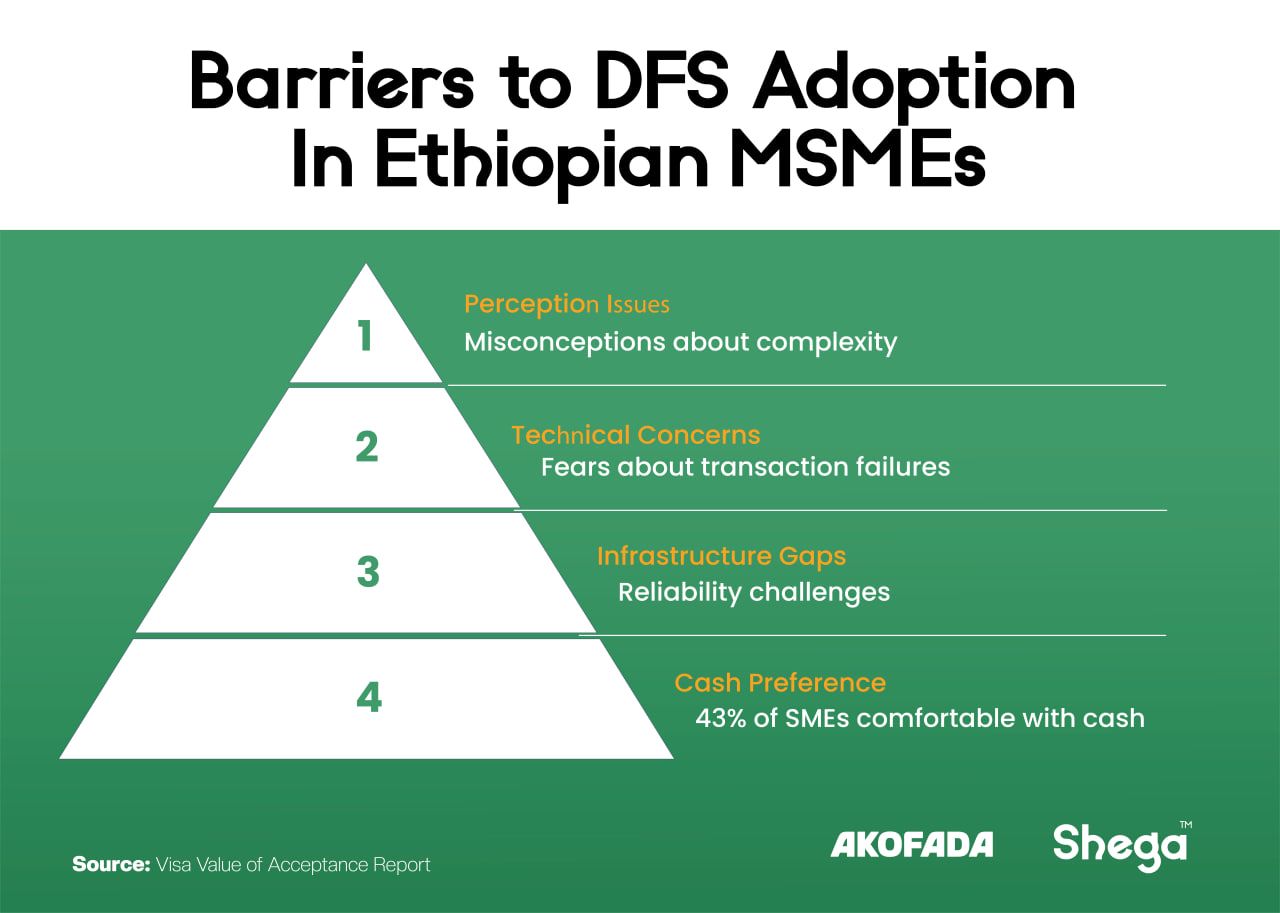

Some vendors operated from a small rectangular wooden box, which was wheeled away at the sight of officers from the Addis Ababa Code Enforcement Authority (Denb). While these salesmen, who were all men, spoke a little too fast and seemed in a hurry to make a sale, they readily accepted digital payments to my convenience. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the mostly female vendors who sold groceries in relatively more stable small and medium-sized stations only accepted cash.

Fatuma Mohammed, who makes a living selling vegetables and spices, says she feels uncomfortable using digital financial services. However, when the sales prospect is too alluring to pass, she receives payments through the nearby shopkeeper. Even after learning about potential credit access via mobile money, the devout Muslim refuses to engage, unwilling to receive and pay interest.

“I just don’t see the benefits,” Fatuma says.

Other vendors in the area, who mostly offer textile products obtained through informal channels, don’t share any of that concern. One of them pointed out that he does not see much difference in accepting digital payments while relaying fears that his account could get blocked one day. However, he readily takes loans out from telebirr’s mobile money service whenever he is a few pennies short of rent or a sudden expense emerges. The vendor blurted out in laughter when I asked him if he considered himself a small enterprise.

The few small business owners in the outskirts of the capital represent a mere fraction of the 2.2 million Medium, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) operating in the country. Of course, after assuming a standard definition of MSMEs.

Despite the increased uptake in the use of digital financial services (DFS) over the past years, use cases are largely limited to urbanites who rely on them in the form of Person-to-Person (P2P) transactions. While some MSME owners still use digital payments, it is limited to fund transfers, hindering the richness of product offerings. Credit access, insurance, investment options, and tailored saving facilities are out of reach for most.

The very high degree of informality in Ethiopia’s economy also introduces another layer of complexity, as most small businesses avoid registration into organizations. These are some of the factors that collude to limit finance access to MSMEs, which have spilled over into the digital ecosystem. Ethiopia’s MSMEs remain mostly on the sidelines of the digital upsurge despite their significance in moving the gears and wheels of the economy. Understanding the unique economic identities of Ethiopia’s MSMEs will prove critical in advancing both DFS adoption and addressing their financial constraints.

Every week, at least one seminar, workshop, or panel discussion on MSMEs in Ethiopia takes place at a hotel in Addis Ababa. Development actors and government officials constantly trade insights into the prospects of this amorphous economic segment.

Nevertheless, defining these enterprises has been nearly as challenging as supporting them ever since the acronym became popularized in the 90s. A World Bank document from 2019 vividly highlights the difficulties by highlighting the inefficacy of the MSME label in Afghanistan and Brazil. Sure, both might have less than a certain number of employees and fork up a given amount in annual turnover, but it in no way means they can be treated the same. The metrics would fall even flatter if applied to the Ethiopian context with its own set of constraints and opportunities.

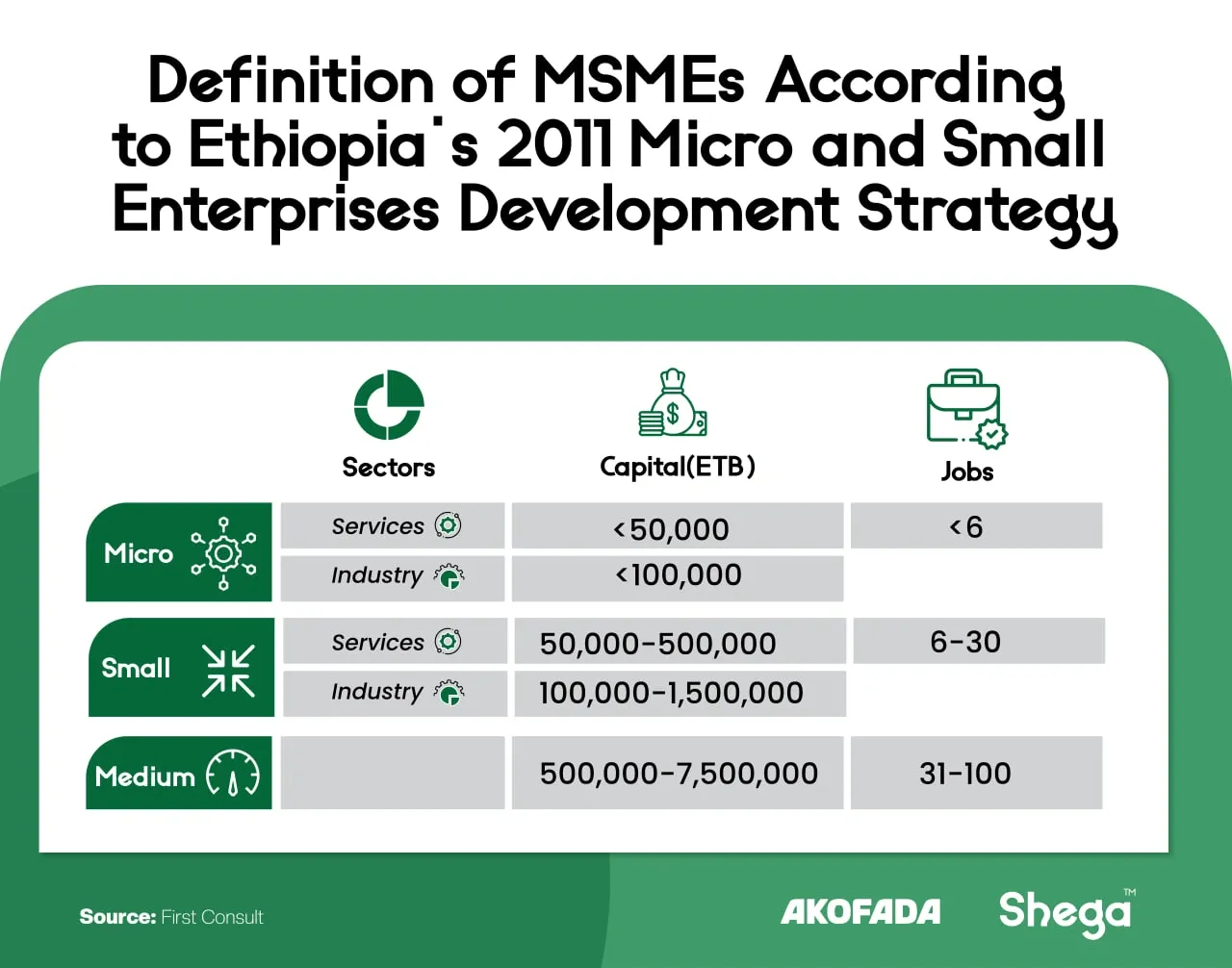

For instance, the Council of Ministers, through its Federal Micro and Small Enterprise Development Agency establishment regulation enacted in 2011, attempted to clearly define what MSMEs were, categorizing service sector micro businesses as those with less than 50,000 birr in capital and up to five employees. The regulation expands the capital base to half a million for small enterprises and up to 30 workers, including the owner and his family. Leaving aside qualms about whether this definition fits the current economic landscape, it would be tough to find many Ethiopians who refer to a business with 30 employees as small. Furthermore, Ethiopia’s shift towards a market-based exchange regime in July significantly erodes the quantitative significance of a capital assessment codified over a decade back.

Interestingly, the Agency has now been split into two. Subsequent pieces of legislation, unfortunately, maintained the delineations laid out in the first legal framework, which many view to be wholly inadequate in its descriptive powers.

Crystallized definitions of MSMEs become critical as tax obligations, potential credit access, and any other regulatory procedure are predicated on their standing in the eyes of the law.

The absence of a unified definition for MSMEs is a challenge recognized by continental organizations like the African Union. One report from the AU centers on this exact problem by highlighting differences in definition across several economies. Countries like Angola categorize MSMEs based on annual turnover and employee size, while others like Egypt take into consideration invested capital and years since incorporation.

Demystifying this ambiguous categorization becomes increasingly important as financial institutions begin to explore credit access in the digital space. Or perhaps metrics that rely on balance sheet estimates to categorize MSMEs should be abandoned altogether for DFS. Maybe the rigor in bookkeeping, documentation of transactions, and clarity of the business model should outweigh old metrics in this age of high-powered computing prowess.

Nevertheless, some technology providers and financial institutions in Ethiopia have ventured into these murky waters, offering a slew of financial products for MSMEs.

In tandem with the popularization of MSME support in development circles, some institutions have experimented with their own set of digital financial innovations in Ethiopia. The most pronounced of these endeavors was spearheaded by Kifiya Financial Technology PLC, initially bolstered by the Mastercard Foundation and the International Finance Corporation (IFC). Qena, an AI-driven platform developed by Kifiya, enables banks to offer uncollateralized lending solutions to MSMEs through a credit scoring system.

In 2022, Michu, Ethiopia’s first uncollateralized lending app, powered by Qena, came into being through the Cooperative Bank of Oromia’s (COOP) partnership with Kifiya. The service backed by a 10 million dollar guarantee from the Dutch Entrepreneurial Development Bank (FMO), availed a unique product offering. In the three product selections, Michu offers loans ranging from 5,000 birr( Guya) for informal businesses operating without a license up to 100,000 birr (Wabi) for those categorized as medium-sized businesses.

Until now 18.7 billion birr has been disbursed to 1.3 million MSMEs. A second iteration, dubbed Michu 2.0, was rolled out in the financial year to build on the project’s initial achievements.

At least 11 different financial institutions have also piloted and deployed other instances of uncollateralized financing arrangements over the past few years. However, except for Michu, none of them have been purely centered on MSMEs.

The challenge in improving financial services for MSMEs stems from the confluence of forces operating on both sides of the aisle. Despite the marked growth in the use of DFS tools for P2P payments over the past few years, it has not necessarily translated into credit facilitation.

The last financial stability report by Ethiopia’s central bank indicates an annual growth of 50% in digital payments, which reached 9.6 trillion birr at the end of the last fiscal year. However, the figure, which amalgamates ATM, POS, mobile, and internet banking, fails to disaggregate the data in any meaningful way that helps extract insight into business transactions. While the Report indicates 4.1 million new digital credit users in the year, it falls short in complementing the figure with the types of loans or their beneficiaries.

Nevertheless, the accelerated expansion of digital finance is also exhibited by reports like that of the national switch operator Ethswitch. P2P interoperable transactions even exceeded ATM transfers at around 257 billion birr over the last financial year. This figure should raise an eyebrow as much as it appears impressive. A significant portion of P2P transfers entails payments for merchants despite both sides of the transaction failing to get the benefits of a robust payment infrastructure. Customers are charged transfer fees, fail to access potential cash-back options, and perhaps most consequentially for MSMEs, they lack a centralized digital transaction history, which could be used for credit scoring.

A study by the University of Cambridge published last month illustrates the complexity of digital finance accessibility to MSMEs. Upon surveying over 800 enterprises distributed across seven Asian economies, the Report indicates that simple application procedures and quick disbursements served as powerful factors in MSME finance. It illustrates the importance of tailoring designs to prevailing demand trends in communities for accelerating support of MSMEs.

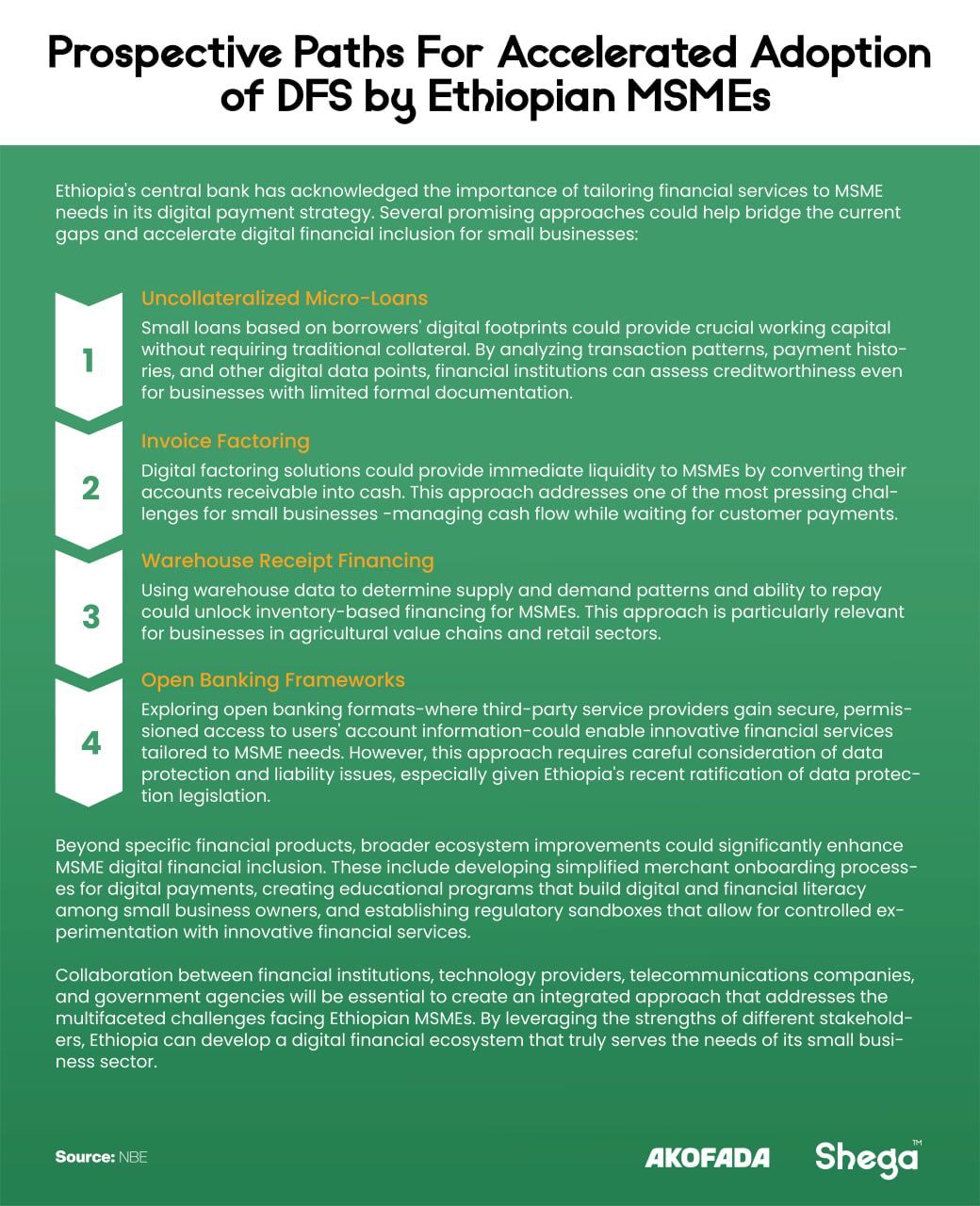

Ethiopia’s central bank has acknowledged the importance of tailoring financial services to the needs of MSMEs in its digital payment strategy. Small, uncollateralized loans based on a borrower's digital footprint, factoring to provide immediate liquidity to SMEs by converting their accounts receivable into cash, and the use of warehouse data to determine supply & demand and ability to repay have been considered. The potential to explore open banking formats, which entails third-party service providers gaining secure and permissioned access to users’ account information to develop tailored digital finance products, has also been suggested by some experts. However, this could usher in risks related to liability between data holders, users, and owners for a country that just recently ratified a data protection proclamation.

Despite informality in the MSME sector being a ubiquitous phenomenon across Africa, the rapid rise of DFS tools has helped in minimizing access barriers. In countries like South Africa, where the biggest banks have started to remove ATMs due to the massive adoption of digital alternatives, MSMEs have benefitted from an array of new opportunities. Fueled by institutions like Tyme Bank, the country’s first fully digital bank, which cut operational costs by half, and the declining costs of PoS machines, South Africa is quickly becoming a cash-lite economy. Recent findings indicate that nearly 90% of MSMEs in South Africa accept payments through digital services. This is a stark contrast to Ethiopia, where a recent survey report by Visa showed that just one in five cash-only Enterprises currently plan to invest in digital payment technologies.

Among the key barriers challenging the emergence of contemporary financial solutions for Ethiopian MSMEs has been the conflation of the owner’s personal bank account and that of the enterprise. This is particularly significant when considering that nearly 94% of these enterprises are sole proprietorships, according to one report. The absence of solid bookkeeping practices renders the development of a robust digital footprint that can be leveraged for credit scoring quite cumbersome. Compounded by a historically uneasy environment for doing business, MSMEs in Ethiopia have faced difficulties accessing finance, scaling operations, and diversifying their portfolio.

A 2022 report by CIPE, Shega, and Sway Ventures on the inclusion of micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) in Ethiopia’s digital economy proposes several policy recommendations. Among them, the report highlights the need to develop a digital lending strategy and framework to encourage banks, MFIs, and non-banking financial institutions to provide digital financial services for MSMEs. It also calls for scaling up credit rating by integrating the Digital ID initiative with the Credit Reference Bureau (CRB) and implementing specific data integration policies. Additionally, it emphasizes the importance of adopting or replicating MSME-focused innovations to enhance financial inclusion and access to digital services.

While DFS tools don’t entail a panacea for the nexus of challenges faced by Ethiopia’s MSMEs, they can serve as a foundation to springboard rapid growth. The experiences of MSMEs in Bangladesh, Vietnam, and India illustrate how DFS may help reduce informality and foster financial inclusion. South Africa’s fintech firms have particularly made innovative headway with daring services that have included crowdfunding for MSMEs using predictive analysis for credit scoring, unsecured lending to MSMEs with repayment recovered through a percentage of card swipes, using proprietary algorithms based on sales, and much more.

Both economic growth and financial inclusion are rendered unthinkable without onboarding MSMEs, whatever their definition might be. A symbiosis of enterprises and emerging DFS will prove to be a critical anchor in achieving the twin objectives.

👏

😂

❤️

😲

😠

Munir Shemsu

Munir S. Mohammed is a journalist, writer, and researcher based in Ethiopia. He has a background in Economics and his interest's span technology, education, finance, and capital markets. Munir is currently the Editor-in-Chief at Shega Media and a contributor to the Shega Insights team.

Your Email Address Will Not Be Published. Required Fields Are Marked *