Progress for 0 ad

Progress for 1 ad

Progress for 2 ad

Progress for 3 ad

Bemnet Tafesse

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Competition in digital financial services serves customers by promoting innovation and efficiencies, leading to lower prices, greater choice, better quality services, and improved products. It can also play an essential role in extending financial access to financially underserved individuals.

Despite reforms allowing fintechs and non-bank entities to enter the market, unfair trade practices, government favoritism, and limited competition persist in the emerging sector. The absence of sector-specific competition laws exacerbates this problem, stifling innovation and disadvantaging consumers.

This piece is the latest from AKOFADA (Advancing Knowledge on Financial Accessibility and DFS Adoption), a project working to increase knowledge and transparency within Ethiopia’s DFS ecosystem.

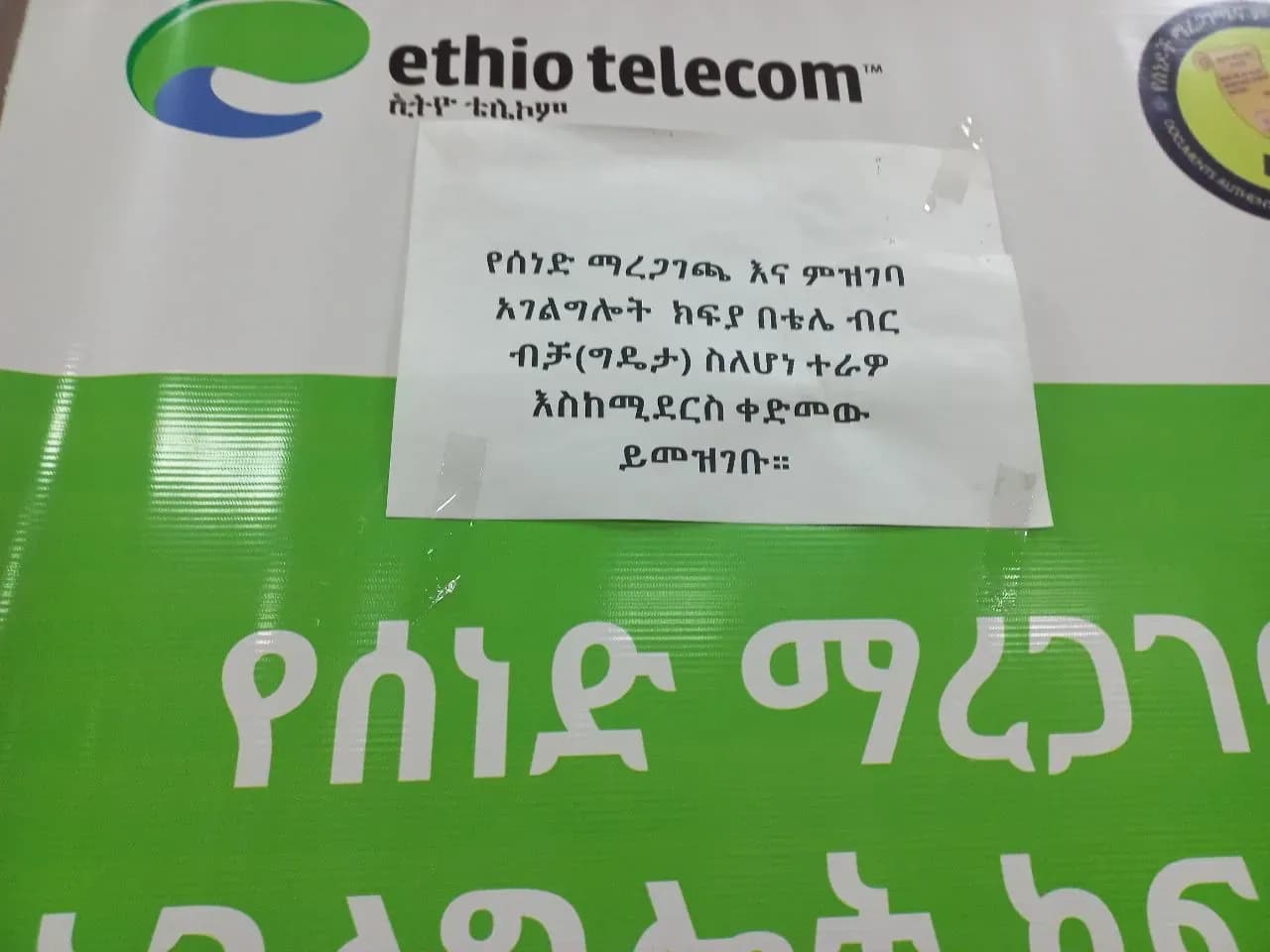

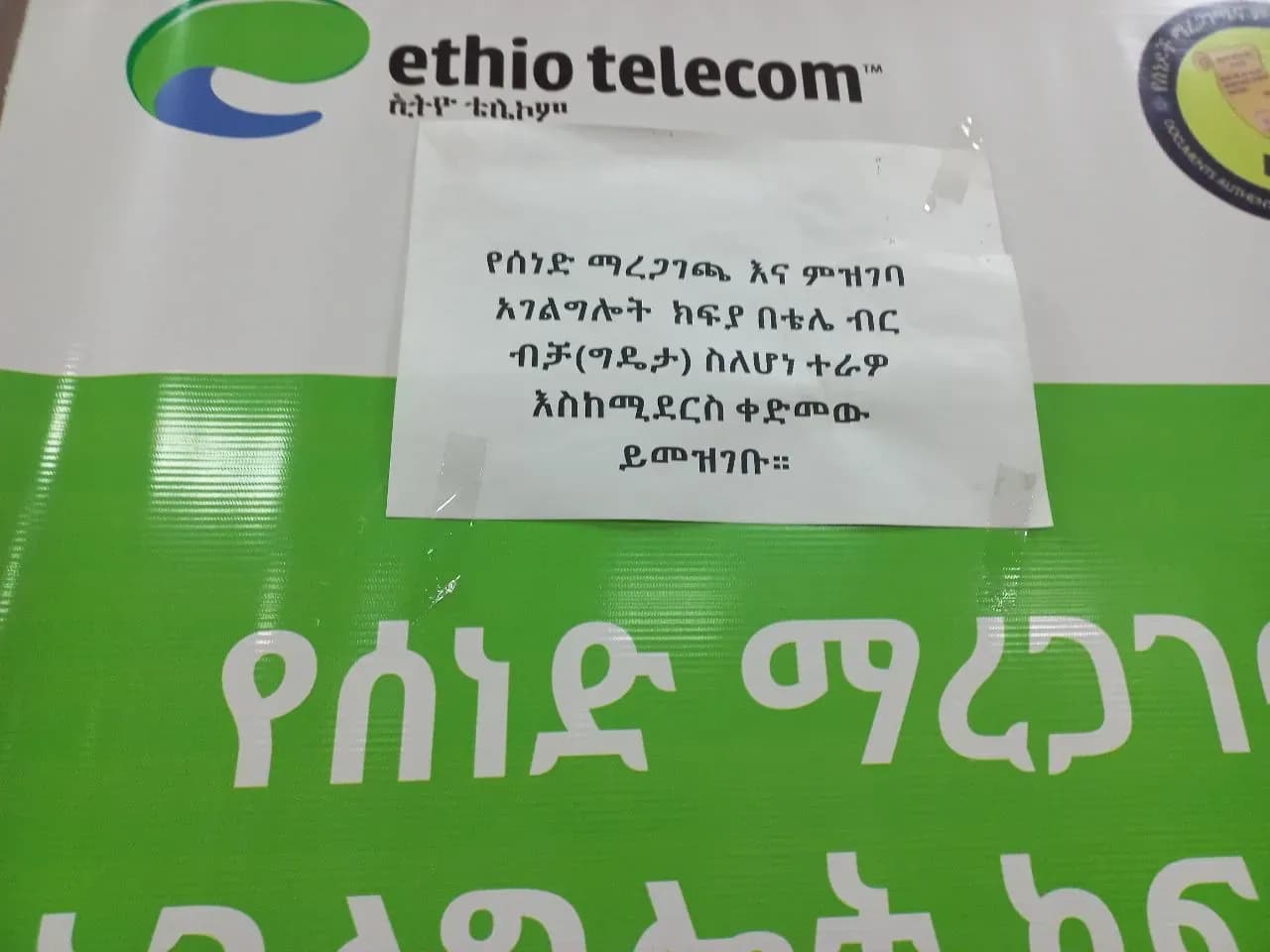

Featured Image: A notice displayed at a Federal Documents Authentication and Registration Services (DARS) branch, stating that payments are exclusively accepted via telebirr. Source: Shega

_____

One weekday last month, I found myself waiting in a long queue at one of the branches of the Federal Documents Authentication and Registration Services (DARS) to finalize a sales contract on behalf of my client. As a lawyer, I frequently visit this government agency to authenticate various types of contracts.

The authentication process began with submitting the necessary documents for review, followed by a series of checks and stamps across different counters. After nearly an hour and a half in a crowded pavilion, I reached the final step: payment. It was here that I encountered an unexpected hurdle—DARS only accepts service fees through telebirr and CBE-Birr. A notice posted nearby made it clear: payments via other digital platforms, including those provided by private banks and fintech operators, were not accepted.

My initial insistence on using an alternative platform led to a brief clash with the officer handling payments. Ultimately, I had to rely on a friend to process the payment through one of the approved channels, extending my stay at the agency by another half an hour.

This seemingly minor inconvenience highlights a significant issue in Ethiopia's digital financial services (DFS) ecosystem—unfair trade competition and practices.

Despite Ethiopia's digital financial service (DFS) sector witnessing structural and legislative reforms, including increased participation by non-bank and foreign telecom operators, the sector continues to face systemic challenges.

Industry players often voice concerns about the entrenched advantages enjoyed by state-owned giants Ethio Telecom and the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (CBE).

While these usual suspects often bear the brunt of public blame, unfair trade practices also occur between themselves. Government favoritism, disproportional pricing at the cost of the end user, blocking of access, and refusal to interoperate are some of the prevalent unfair trade practices seen in Ethiopia’s DFS ecosystem.

These challenges are further compounded by the absence of sector-specific competition laws. This not only leaves private players struggling to secure a fair foothold in the market but also imposes significant burdens on end customers, manifesting as increased costs, inconvenience, and, in some cases, denial of access to essential government services.

The common notion that "competition fosters quality" holds particularly true in the digital financial services (DFS) landscape, where increased competition can drive significant benefits. According to a 2019 study by CGAP, a think tank, competition serves customers by promoting innovation and efficiencies, leading to lower prices, greater choice, better quality services, and improved products.

The report, titled “Fair Play: Ensuring Competition in Digital Financial Services,” further highlights that, at a national level, competition helps curb excessive concentrations of economic power and reduces operational risks from service outages. From a financial inclusion perspective, greater competition increases the likelihood that DFS will reach low-income individuals who are currently excluded or underserved by the financial sector.

This is particularly crucial in Ethiopia, where a significant portion of the population remains unbanked or underbanked, with only 45% having access to formal banking services. By promoting fair competition, regulators can encourage new market entrants, including fintech startups that often focus on serving marginalized communities. These players can introduce innovative solutions tailored to the unique needs of underserved populations, such as mobile money services, microloans, and savings products with lower fees and minimal knowledge barriers.

However, CGAP notes that DFS markets are prone to concentration—a challenge not unique to Ethiopia. Many DFS markets in emerging economies lack sufficient competition. Two often-cited examples are M-PESA in Kenya and bKash in Bangladesh, which commanded upwards of 90% market share in their respective markets.

While M-PESA and bKash’s dominance has undeniably contributed to the rapid growth of mobile money in their countries, competitors have raised concerns about market abuse and stifling of fair competition.

In October 2024, Kenyan lawmakers renewed their push to force Safaricom, the country's largest telecommunications provider, to separate from M-PESA, its highly profitable mobile money service. This initiative follows the reintroduction of the 2022 Information and Communications (Amendment) Bill, aimed at creating two separate entities to enable more regulatory scrutiny and reduce Safaricom's market dominance.

While market share serves as a rough indicator of competitive dynamics, the extreme cases of Kenya and Bangladesh reflect broader trends seen in DFS markets across countries like Uganda and Zimbabwe, where one or two providers dominate. Such high levels of market concentration not only limit customer choice but also create conditions for abuse—whether through disadvantaging rivals, harming consumers, or fostering cartel-like behavior.

Before analyzing the current status of Ethiopia’s DFS ecosystem, it is important to first shed some light on notable legislative pieces that significantly shape the DFS ecosystem.

Up until 2020, the Ethiopian DFS ecosystem has been reserved for digital platforms catered to by financial institutions. This development led to the emergence of various mobile money platforms like Hello-Cash and M-birr as a result of successive ventures undertaken between system developers and financial institutions.

However, the growth and inclusiveness of DFS services, mainly mobile money services (MMS), failed to show a significant leap, lagging behind regional peers. For instance, data from the year 2019/20 depicts that only 15.8% of the adult population had a mobile money account, painting a grim picture for a demographic group constituting more than 60 million of the population.

Experts pinned this lackluster performance on the financial industry's emphasis on the expansion of conventional facilities and the exclusion of mobile network operators (MNOs) and fintechs. This unnerving trend starts to take a startling turn following the promulgation of the Payment Instrument Issuers Directive and the Payment Instrument Directive (ONPS/01/2020 and ONPS/02/2020, respectively).

These regulations and their subsequent amendments have opened the door for non-bank entities and fintechs to enter the evolving landscape of digital financial services, paving the way for increased competition and innovation in the sector by removing statutory impediments.

In this regard, Ethio telecom emerged as a formidable force, launching its mobile money service, telebirr. Leveraging its large customer base, telebirr managed to pass 20 million subscriber marks within 10 months of its inception.

However, as Ethiopia’s DFS ecosystem begins to open up, concerns persist about the lack of genuine competition in key emerging sectors. The working paper by the U.S.-based think tank CGAP highlights that market asymmetries in DFS often stem from structural, strategic, and statutory barriers, which dominant firms frequently exploit:

Structural Impediments: These arise from inherent characteristics of the DFS market, making it challenging for new entrants to compete with established incumbents. Examples include network effects, high sunk costs, and economies of scale and scope.

Strategic Impediments: These result from deliberate actions by dominant firms to discourage competition. Unlike structural barriers, strategic barriers are within the control of market actors and include tactics such as restricting access to communication and payments infrastructure, exclusive agent contracts, data silos, and refusal to interoperate.

Statutory Impediments: These stem from regulatory frameworks that may inadvertently favor incumbents or restrict competition. Licensing requirements and distinctions between regulations for banks and non-banks are common examples of statutory barriers in DFS markets.

Concerns over government favoritism in Ethiopia's digital financial services (DFS) ecosystem are far from a secret. The sector is increasingly defined by the overwhelming dominance of state-owned enterprises, notably Ethio Telecom and the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (CBE).

Together, telebirr and CBE Birr account for 40% of the 204 million digital accounts in Ethiopia as of June 2024 (telebirr 47.6 million and CBE birr 34 million users).

When Safaricom entered Ethiopia's telecom market in 2021 as part of the country’s telecom liberalization, it was excluded from offering mobile payment services. Safaricom was only granted a mobile money license in May 2023. In the two years between Ethio Telecom’s launch of telebirr in May 2021 and Safaricom’s entry into the mobile money space, telebirr amassed over 31 million subscribers and facilitated transactions worth more than 379 billion birr ($7 billion).

This preferential treatment became again apparent in April 2023, when the Ethiopian government enforced mandatory electronic payments at gas stations in the capital. Initially, telebirr was set to be the sole electronic payment option—sparking heated debates between officials and fuel distributors. Following public backlash and stakeholder pressure, the government ultimately allowed all banks to facilitate fuel payments electronically. However, non-bank payment system providers such as Chapa, ArifPay, and SantimPay, as well as Safaricom-operated M-Pesa, are yet to be included in these fuel transactions.

Furthermore, numerous government institutions have adopted telebirr and CBE Birr as their preferred payment methods. Ethio Telecom and CBE have leveraged their connections with government agencies to secure exclusive agreements, channeling substantial funds through their platforms for public services.

The state’s inclination toward these platforms is also evident in public statements. In a parliamentary session last year, Ahmed Shide, Minister of Finance, hinted at the possibility of channeling government salary payments through telebirr.

While some industry experts defend these alliances, attributing them to the incumbents' robust institutional capacity and their ability to handle large-scale transactions securely, others remain skeptical. They argue that these agreements primarily stem from preferential treatment rather than sound business rationale.

Legal professionals offer an additional perspective. A corporate litigation lawyer with over a decade of experience, speaking anonymously, pointed to Ethiopia's Trade Competition and Consumer Protection Proclamation (TCCPP). Specifically, Article 7(1)(b) prohibits agreements that could significantly impede competition. "Maintaining a delicate balance between economic priorities and market competition should be the focus," the lawyer emphasized.

These exclusive agreements have made it particularly difficult for late entrants like Safaricom to compete for partnerships with government agencies. During a recent visit by members of Parliament to Safaricom’s headquarters, the company’s Chief External Affairs Officer, Andualem Admassie (PhD), remarked, "Safaricom pays its taxes through telebirr."

Safaricom Ethiopia has expressed its dissatisfaction with what it perceives as monopolistic practices by Ethio Telecom, urging the government to ensure equal access to open platforms.

A recent GSMA report, published in October 2024, reinforces this stance, recommending the fair and timely implementation of Ethiopia’s telecom reform agenda to create a level playing field for all market participants.

According to CGAP, another significant barrier to competition arises when banks or regulators unfairly restrict access or implement disproportional pricing strategies to disadvantage other players in payment settlement infrastructures. Such practices put the consumer at the receiving end of this competition.

According to CGAP, a significant barrier to competition arises when banks or regulators unfairly restrict access or implement disproportionate pricing strategies to disadvantage other players in payment settlement infrastructures. These practices ultimately leave consumers bearing the brunt of reduced competition.

An example here is CBE's recent pricing strategy, which imposes disproportionately high fees for transactions from its mobile banking platform to telebirr. For instance, sending as little as five birr incurs a fee of ten birr—double the transaction value. This has sparked widespread criticism, with many deeming the fees unreasonable.

For instance, sending as little as five birr incurs a fee of ten birr—double the value of the transaction itself. This pricing strategy has sparked widespread criticism, with many calling it unreasonable.

Despite public outcry, the fee remains unchanged, suggesting an intentional approach. In contrast, CBE imposes zero fees for transfers between CBE Mobile banking app and CBE Birr. The bank has even launched advertising campaigns emphasizing this zero-fee advantage, further highlighting the preferential treatment it is giving to its own mobile money service at the cost of others.

While some may argue that such actions are simply pricing strategies, institutions like CBE might justify favoring their own platform, CBE-Birr, over other mobile money platforms to limit monetary outflows. However, this approach can discourage the settlement of interoperable payments, disadvantaging users and burdening them with unnecessary costs.

Interoperability among actors is also another issue further complicating the DFS landscape in Ethiopia. While the integration of services among different financial platforms is crucial for enhancing user experience and promoting competition, the current state of affairs reveals significant technical and legislative gaps.

Despite, the national switch operator, EthSwitch, coming a long way since beginning its operation eight years ago it has not achieved a full wallet-to-wallet integration among all actors across the board while telebirr still remains outside its ambit. This fact has been nudging fintech operators as it goes astray from the payment system operators’ directive, which confers the sole mandate to undertake national integration between instrument issuers to Ethswitch.

After its inception as a payment instrument issuer, telebirr has operated independently, undertaking one-on-one integrations with several banks and fintech operators. While prior experiences suggest that actors typically seek integration with other service providers, there are insufficient guidelines outlining how these one-on-one integrations should occur or under what circumstances they are allowed.

Furthermore, telebirr does not allow sending money to other mobile money platforms. Both M-Pesa and telebirr do not support inter-platform money transfers.

Safaricom execs see this limitation as hindering the potential for seamless financial transactions, highlighting the need for collaboration between the two networks to enhance digital financial inclusion in the country.

“Monopoly is a contradiction to liberalization. We have 32 banks; we have multiple fintech financial institutions; all of them should be able to offer digital payments. So, we ask policymakers if we really want to accelerate digital Ethiopia, we should try to get all the financial institutions to give them equal access to offer digital payments,” Wim Vanhelleputte, CEO of Safaricom Ethiopia, was quoted as saying by The Reporter.

Additionally, customers should be able to access mobile money services from different operators, regardless of the SIM card they use. The focus should remain on delivering value and enhancing user experience, not on creating barriers that stifle competition.

However, this is not the case in Ethiopia. Users cannot open an M-PESA account with an Ethio Telecom SIM card, nor can they access M-PESA services with an Ethio telecom SIM card.

This limitation places an unnecessary burden on customers, forcing them to own and maintain multiple SIM cards if they wish to use both services.

In contrast, Kenya has made significant strides in this area. Mobile network operators such as Telkom, Safaricom, and Airtel have not only ensured interoperability across their platforms but also enabled seamless mobile money payments to any merchant till number, regardless of the operator. This advancement has significantly boosted the adoption and convenience of cashless payments in Kenya.

Examining fair trade practices through a legal lens reveals the absence of sector-specific competition laws in Ethiopia's DFS ecosystem. Instead, relevant provisions are scattered across various legislative instruments. A closer look at legislative patterns indicates a strong emphasis on consumer protection through multiple legal measures, including the Financial Consumer Protection Directive introduced in 2021. While this directive addresses critical issues such as cost transparency, data protection, product design, and complaint-handling mechanisms to enhance the consumer experience, it falls short of tackling trade competition dynamics directly.

The primary law governing competition in Ethiopia, the Trade Competition and Consumer Protection Proclamation, was enacted over a decade ago to curb cartel-like behavior and anti-competitive practices. The law addresses issues such as abuse of market dominance, anti-competitive agreements, concerted practices, and unfair practices. Additionally, it empowers consumers to purchase goods and services based on their own choices.

However, it lacks the specificity required to address the unique and rapidly evolving characteristics of the DFS sector. Research by Dawit Gebru, titled "Regulating Mobile Money Services and Competition in Ethiopia," underscores these limitations. Key unresolved issues include the absence of clear definitions for essential terms, inadequate guidelines for assessing and designating market dominance, and unclear delineation of oversight responsibilities among regulatory bodies.

The rapid pace of digitization and its critical role in advancing financial inclusion have compelled many nations to adopt comprehensive regulatory approaches. For instance, Brazil introduced a digital markets law to address a wide range of issues in its growing digital economy. This legislation explicitly defines market dominance and sets clear criteria to prevent the abuse of dominant positions by digital platforms. It mandates increased transparency, enabling consumers to better manage their data and fostering interoperability and data portability. By identifying specific behaviors that constitute market dominance, the bill not only protects free competition but also ensures a fair and equitable digital landscape.

Ultimately, robust legal frameworks are essential for fostering competition in Ethiopia's DFS ecosystem. Such frameworks promote equitable access, encourage innovation and fair practices, and dismantle monopolistic practices, empowering the end user.

To achieve this, the central bank should issue a new directive specifically addressing these challenges within the financial sector, while the Ethiopian Communications Authority (ECA) might consider issuing or revising directives on fair competition within the telecom sector. Additionally, establishing a clear separation between telecom and financial services businesses, alongside transparent and equitable arrangements, will be crucial.

As Ethiopia works to bridge existing gaps in financial service access, effective regulation will be pivotal in ensuring all citizens benefit from the digital economy, contributing significantly to the country's broader financial inclusion goals.

👏

😂

❤️

😲

😠

Bemnet Tafesse

Bemnet Tafesse is a lawyer and freelance content developer with a keen focus on digital finance, data protection, and cyber laws. Passionate about fostering a transparent and accessible digital finance landscape, he currently works as a legal officer at an import-export firm Medonus Trading.

Your Email Address Will Not Be Published. Required Fields Are Marked *