Progress for 0 ad

Progress for 1 ad

Progress for 2 ad

Progress for 3 ad

Kaleab Girma

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Once a vital part of Ethiopia's financial services, bill aggregation has faded from the spotlight. Despite the rapid expansion of digital financial services, the future of bill aggregation remains uncertain. What role can bill aggregators play in the nation's digital financial transformation?

This piece is the latest from AKOFADA (Advancing Knowledge on Financial Accessibility and DFS Adoption), a project working to increase knowledge and transparency within Ethiopia’s DFS ecosystem.

Featured Image: Customers paying their electricity bills at Ethiopian Electric Utility (EEU) customer service centers in Addis Ababa on February 25, 2023. Source: EEU

____

Five years ago, I was an assignment editor at Fortune, a local weekly business newspaper. It had been less than a year since I began my journalism career at the same institution. My responsibilities included assisting reporters with their work, occasionally editing first drafts, and reporting on my own stories.

At the time, our editor-in-chief, the most senior editor leading the editorial team, was traveling abroad for a work visit. With no senior personnel above me, I suddenly found myself tasked with leading the team of reporters to deliver the upcoming Sunday edition.

The challenge was significant, but there was no turning back. We would fail or succeed—either way, Sunday was approaching, and we had to do our best.

The paper featured a dedicated section called Agenda, where a hot topic was discussed in detail. This section always took priority, in addition to the nine other stories we were expected to produce within the week.

Our team consisted of strong and experienced reporters, so sourcing news stories wasn't a challenge. However, for Agenda, we needed something impactful. At that time, a pressing issue was affecting many households and residents: paying utility bills had become a nightmare. Long queues were forming at several Ethiopian Electric Utility customer service centers in Addis Ababa as clients struggled to pay their bills.

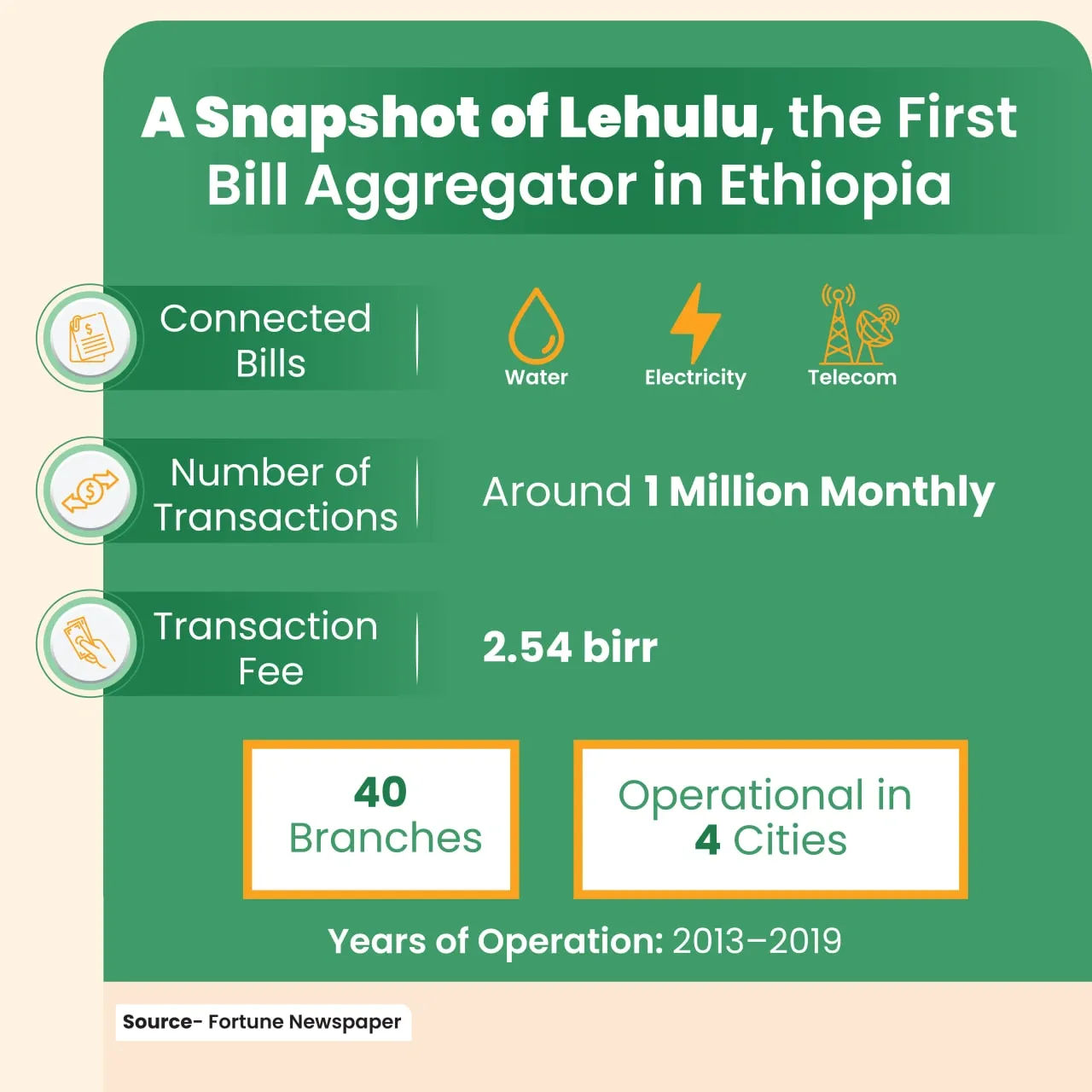

For the previous seven years, utility payments for electricity, telecom, and water had been managed by Lehulu, a one-stop shop for various utility payments operated by Kifiya Financial Technology, a public-private partnership (PPP). However, in August 2019, Lehulu handed over the responsibility to the respective government offices after its contract with the government expired.

Customers now had to pay their electricity and water bills at each respective government office. What used to take a few hours was taking several days, as these understaffed government offices were unprepared for the influx of billpayers.

We believed this was a strong story for Agenda, so we assigned one of our senior reporters to cover it. He visited customer service centers, spoke with frustrated clients, overwhelmed employees, and provided an analysis of why the situation had deteriorated by interviewing various stakeholders.

I edited the draft; our copy editor cleverly titled the piece "Electric Billing Gets Worse Before it Gets Better," and the story, along with others, successfully made it to print.

At the time, anything related to Lehulu, the first bill aggregator in Ethiopia, was a major story. Reporters closely followed developments, and the public paid attention because these issues directly impacted them.

But now, that era feels like a distant memory, almost forgotten as it fades into the past. Fast-forward five years, and the landscape has transformed dramatically, driven by telecom liberalization and a wave of digitization sweeping across the country. Fintech is booming, the Ethiopian banking sector is opening its doors to foreign banks, Safaricom has entered the scene, and—get this—drivers are now paying for fuel via Ethio Telecom’s mobile money platform! It’s wild!

However, the same cannot be said for bill aggregation, which was once an essential part of Ethiopia's financial services. Before its closure, Lehulu allowed clients to pay their electricity, water, and telephone bills, as well as traffic penalties at 40 branches—four in Bahir Dar, four in Meqelle, and 32 in Addis Abeba. Kifiya served around a million customers monthly through this system.

Now, such transaction figures are not coming from the sector, and the role that bill aggregators can play in Ethiopia's digital financial services seems to have been forgotten.

Today, Kifiya stands as one of the major players in Ethiopia’s digital financial ecosystem. Its flagship product, Qena—Ethiopia's first digital lending solution—leverages artificial intelligence to assess the creditworthiness of micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) and individuals. Qena powers Cooperative Bank of Oromia's collateral-free lending platform, Michu, as well as Wegagen Bank’s Efoyta.

Recently, Kifiya partnered with The Mastercard Foundation to launch a $100 million program aimed at making uncollateralized digital lending the new normal for MSMEs.

But before reaching these milestones, the IT company, founded in 2010, first made its mark with Lehulu.

Launched in 2013, long before Ethiopia enacted its public-private partnership law, Kifiya secured an agreement with the then Ministry of Communications & Information Technology to facilitate utility bill payments. This pioneering one-stop payment facility, called Lehulu (an Amharic word meaning "for everything"), was designed to replace the existing utility payment centers of then Ethiopian Electric Power Corporation (EEPCO), Ethio Telecom, and the Addis Ababa Water and Sewerage Authority (AAWSA).

Initially signed as a three-and-a-half-year contract, the agreement was later extended. Lehulu operated with hundreds of employees and earned 2.54 birr per transaction. While the service was a pioneer and generally satisfactory, it faced few challenges. System disruptions occasionally caused long delays and inconvenienced clients. Delays were reportedly due to utility companies not uploading data for Lehulu in a timely manner.

Kifiya officials also stated that the company was unable to recover its capital expenditure.

In 2019, the Ministry of Innovation and Technology terminated its deal with Kifiya, issuing a circular to government offices to implement user-friendly payment systems through banks. One of the publicly stated reasons for this decision was Kifiya's inability to efficiently manage the growing customer base. After Lehulu was phased out, the state-owned Commercial Bank of Ethiopia took over utility payments.

Since then, the modality of paying for utilities has evolved, with other financial players entering the sector. However, the bill aggregation landscape largely remains fragmented. As for Kifiya, it has moved forward and continued its growth in other areas.

A billing aggregator acts as a bridge between customers, banks, or digital payment platforms, on one hand, and various billers such as utility companies, and telecom providers.

The main role of a billing aggregator is to streamline the bill payment process by combining multiple bill issuers into a single platform. Think of bill aggregators as the glue that binds together some parts of the digital financial ecosystem. They enable payment service providers—like telebirr offering mobile money services or banks offering mobile banking—to easily integrate with entities that need to collect bill payments from customers.

Though they mostly operate behind the scenes, aggregators handle millions of transactions globally every day.

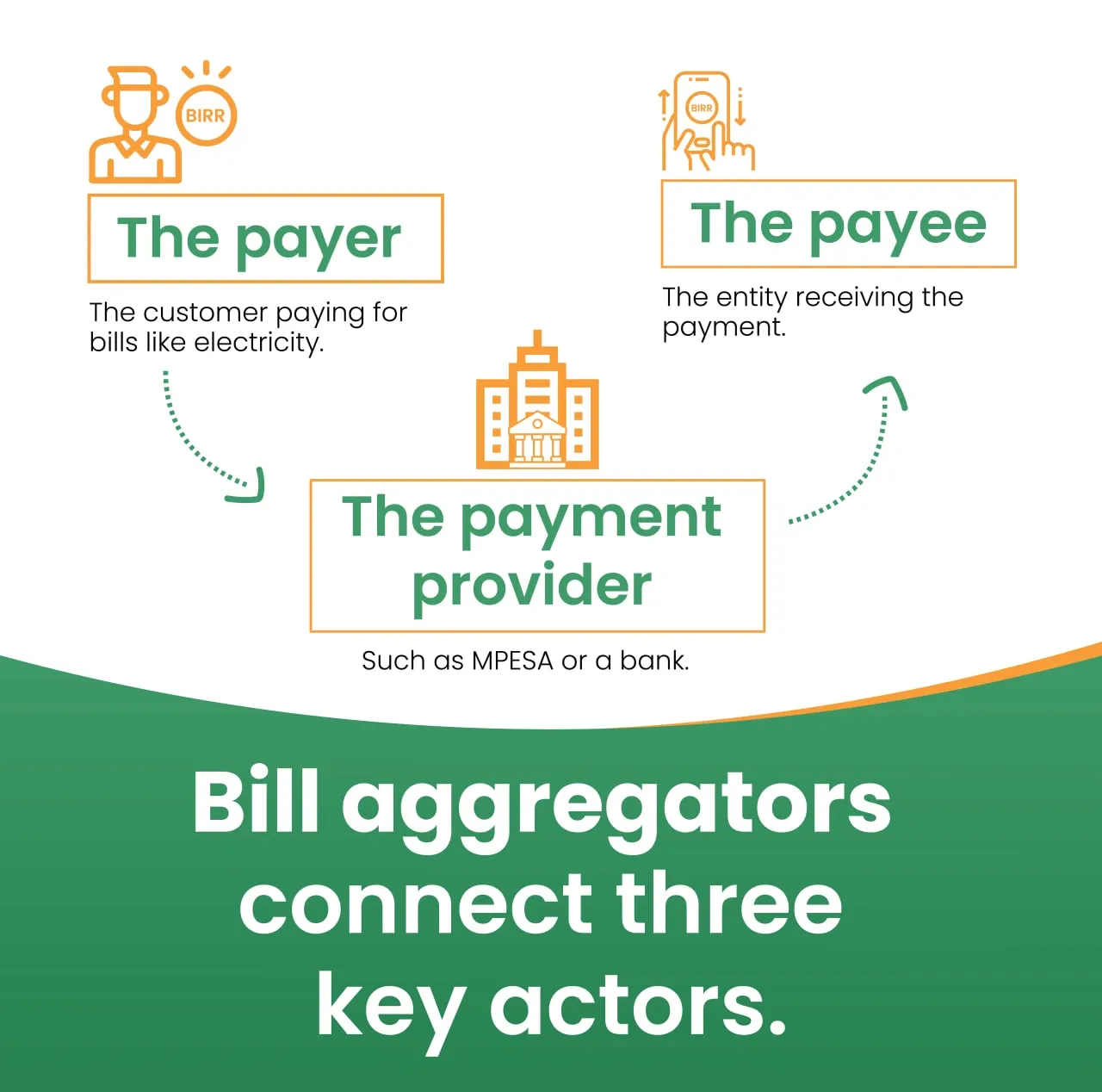

At their core, all aggregators perform two essential functions: integration, connecting the systems of payment providers to third-party services, and offering value-added services (VAS), such as sending payment notifications, reconciling payments, and issuing receipts. At any given time, an aggregator is connecting three key actors:

When researching aggregators, you'll come across a variety of definitions, from companies that recruit merchants to those building their own agent networks. In the case of merchant aggregators, which onboard businesses like e-commerce and food delivery platforms to accept online payments, they are commonly referred to as payment aggregators. These include companies such as Chapa, Arifpay, and Santimpay.

It’s also crucial to define the scope of bills included in bill aggregation. A valuable model to learn from is India, where Ethiopia is currently drawing lessons. India’s Bharat BillPay serves as a one-stop ecosystem for bill payments, offering multiple payment methods and providing instant payment confirmation through SMS or receipts.

Bharat BillPay handles a wide range of bill categories, but recurring payments are the defining core. All recurring payments fall within the Bharat BillPay ecosystem, with current categories including electricity, gas, water, insurance (life, general, health), loan repayments, cable TV, education fees, municipal taxes and services, and subscription fees.

Additionally, categories such as mutual funds, credit card payments, recurring deposits, clubs and associations, and metro recharge are expected to be integrated into Bharat Billpay soon.

The local bill aggregation landscape is relatively small but features some surprising players. Webirr, Unicash, and Derash are the key operators, with Derash being developed by the Information Network & Security Administration (INSA). According to INSA officials, the platform was developed nearly a decade ago, although it was only publicly launched in 2019. The latest available information reveals that Derash has been integrated with over 20 banks.

Re-established in 2014, INSA is an autonomous federal government agency equivalent to the U.S. National Security Agency. Among its responsibilities are protecting critical digital infrastructure and regulating cryptographic products. While Der ash plays a vital role in Ethiopia’s digital financial ecosystem, many stakeholders question INSA’s position in this sector.

Interestingly, Article 15 of INSA's re-establishment proclamation empowers the agency to develop and implement secure information management infrastructures and systems in areas where domestic capacity is lacking, and to charge fees for the services it provides.

The Derash Bill Aggregation Platform facilitates the collection of recurring and ad hoc payments for everyday services, including electricity, water, telecom services, traffic fines, taxes, and customs. Derash plays a significant role in water utility payments, with its integrated platform for water and sewerage services extending to over 20 cities, including Arba Minch, Harar, Bahir Dar, Finote Selam, Injibara, Dessie, and Kombolcha.

One of Derash's key achievements has been its electronic tax payment system, known as e-tax, which contributed significantly to its early success. The platform has collected as much as 90 billion birr annually through its e-tax system.

However, as Ethio Telecom expands its reach, signing agreements with various federal and regional tax authorities, including the Oromia Region Revenue Bureau and the Ministry of Revenue, to collect tax and customs payments through a telebirr-based system, Derash’s transaction volume has started to decline.

WeBirr, a bootstrapped startup, is another prominent player in the sector. Co-founded by three individuals, the firm was established in 2021.

The platform facilitates payments for water bills, education tuition fees, and more. It also collaborates with telebirr. So far, the startup has processed close to 250 million birr in transactions, with the majority stemming from education bills.

Meanwhile, Uni-Cash is a platform that enables customers to make utility and other payments online through mobile phones.

Developed by Atlas Computer Technology in 2020, Uni-Cash is integrated with over a dozen banks. In the capital, its primary focus is on school fees, while its operations in regional cities center on utility payments.

Finally, when examining the licensing regime of bill aggregators in Ethiopia, another gap becomes evident. Their establishment and operation are not regulated by any specific law; instead, bill aggregators function as IT firms and enter into agreements with banks and utility companies to facilitate the payments.

Without an aggregator, each individual integration between a payment instrument provider and a third party would be costly and time-consuming.

In addition, it would require investments in customer support and troubleshooting of technical challenges. Many mobile money providers in East Africa have chosen to use aggregators to avoid these upfront investments, long timeframes, and the onerous tasks of managing reconciliations, payment disputes, and customer support.

However, in Ethiopia, many banks handle system integrations with third-party services independently. For example, Berhan Bank, Zemen Bank, and Awash Bank have developed their own school fee billing system and are actively onboarding schools. DSTV, with its in-house team of developers, handles its own integrations with digital payment platforms.

Ethio Telecom’s telebirr super app is also independently integrating various government services, such as tax payments. Nevertheless, Ethio Telecom does collaborate with existing bill aggregators in Ethiopia—its water utility bill payment option is powered by such aggregators.

telebirr currently lists 30 payments, of which several are reoccurring. Meanwhile, Ethiopia’s digital financial ecosystem boasts more than 20 mobile money wallets and over 30 mobile banking apps. If each of these platforms were to individually integrate just the existing recurring billers covered by telebirr—without even considering future additions—it would require several integrations.

This approach is neither sustainable nor efficient. This fragmented landscape also creates a challenge for entities. Many may not see the value in integrating with every available payment method if they’re already connected to the major ones, which is completely understandable. Often, such demands arise from government agencies. However, this puts smaller and emerging players at a disadvantage, creating an uneven playing field.

A case in point is the Ethiopian Electric Utility (EEU). According to industry insiders, after integrating with Commercial Bank of Ethiopia, telebirr, and Awash Bank, EEU is reportedly refusing to directly integrate with other digital payment channels. Instead, prospective digital financial service (DFS) providers are being directed to integrate through Awash Bank to facilitate electricity payments.

Water bill payments pose their own unique challenges. In Ethiopia, water supply services are managed by city administrations and regional bureaus rather than a centralized entity like the EEU. Cities such as Addis Ababa, Asossa, and Adama supply water and collect their own payments. This fragmented system means that payment platforms must independently integrate with each city’s water bill management system. This is why, when you head to water bill payments on telebirr, you’ll find 23 different utility service providers for various towns and cities.

However, the World Bank is currently funding the development of an innovative Water Utility Management Information System (WUMIS) that will enable customers to pay their water bills for 22 cities in Ethiopia. Once completed, WUMIS will be accessible to both bill aggregators and payment providers.

Bill aggregators are glaringly absent from Ethiopia’s Digital Strategy 2025—the very blueprint meant to steer the nation’s digital transformation. This omission feels like a critical oversight, given the essential role bill aggregation has historically played in streamlining financial services for millions.

Some industry voices argue that INSA, a state entity, should refrain from competing with startups in this space, warning that such competition could choke off entrepreneurial innovation. However, the real challenge for INSA’s Derash platform isn't startup competition—few have emerged to tackle the demand. The true competitor is telebirr, another state-backed giant that dominates the market, creating an uneven playing field for potential new entrants.

These dynamics underscore a troubling reality: the sector is stuck between the weight of public entities and the clout of banks, leaving precious little room for fresh, entrepreneurial energy to thrive with little regard for the final consumer. Yet, this gap could represent a lifeline for those daring enough to innovate. Aspiring entrepreneurs must see the space for what it is—an untapped frontier—and be prepared for the uphill battle ahead. Equally important is the role of the support ecosystem: investors, accelerators, and enablers must recognize the promise in this overlooked market, just as we are seeing with the growing focus on insurtech.

The National Bank of Ethiopia's forthcoming fintech sandbox should also make room for bill aggregators, offering them a chance to innovate, test, and scale. By cultivating an enabling regulatory environment, the government can breathe life back into a sector that was once vital to the nation’s financial fabric.

At its heart, pressing questions remain unanswered in Ethiopia’s digital financial ecosystem: who should take the lead in bill aggregation? Is it INSA, the banks, telebirr, fintechs, or do we need dedicated bill aggregators to fulfill this vital role? What is best for the paying customers?

The decisions made today will not only shape the future of the sector but also influence the broader landscape of digital financial services in the country. For my part, I say: Let us not forget the forgotten.

👏

😂

❤️

😲

😠

Kaleab Girma

Kaleab Girma, an Addis Ababa-based reporter and researcher, with over six years of experience in the field. He currently serves as Shega's Editor-in-Chief and specializes in reporting on small businesses, innovation, technology, and startups in Ethiopia.

Your Email Address Will Not Be Published. Required Fields Are Marked *