Progress for 0 ad

Progress for 1 ad

Progress for 2 ad

Progress for 3 ad

Partner Content

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

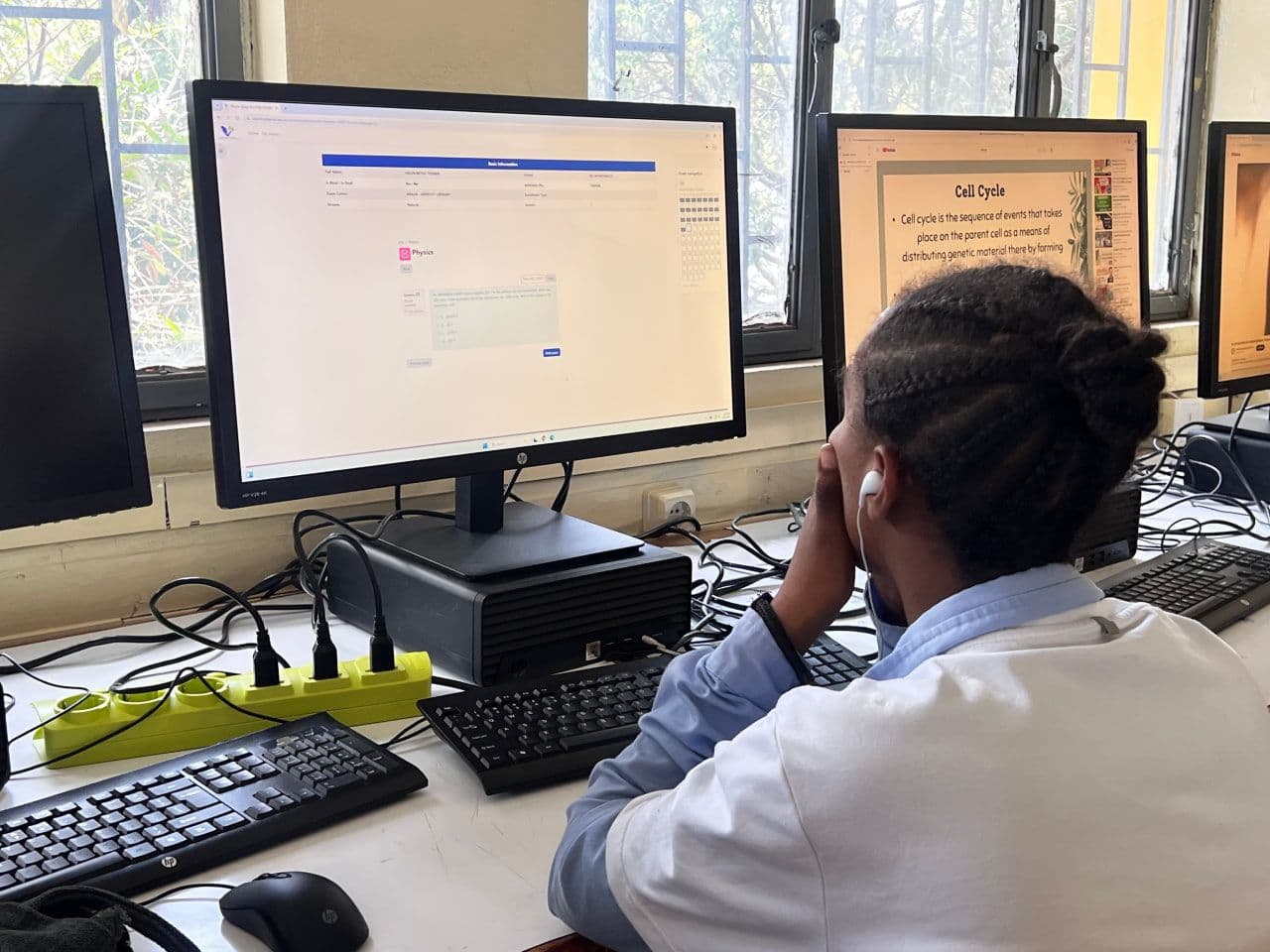

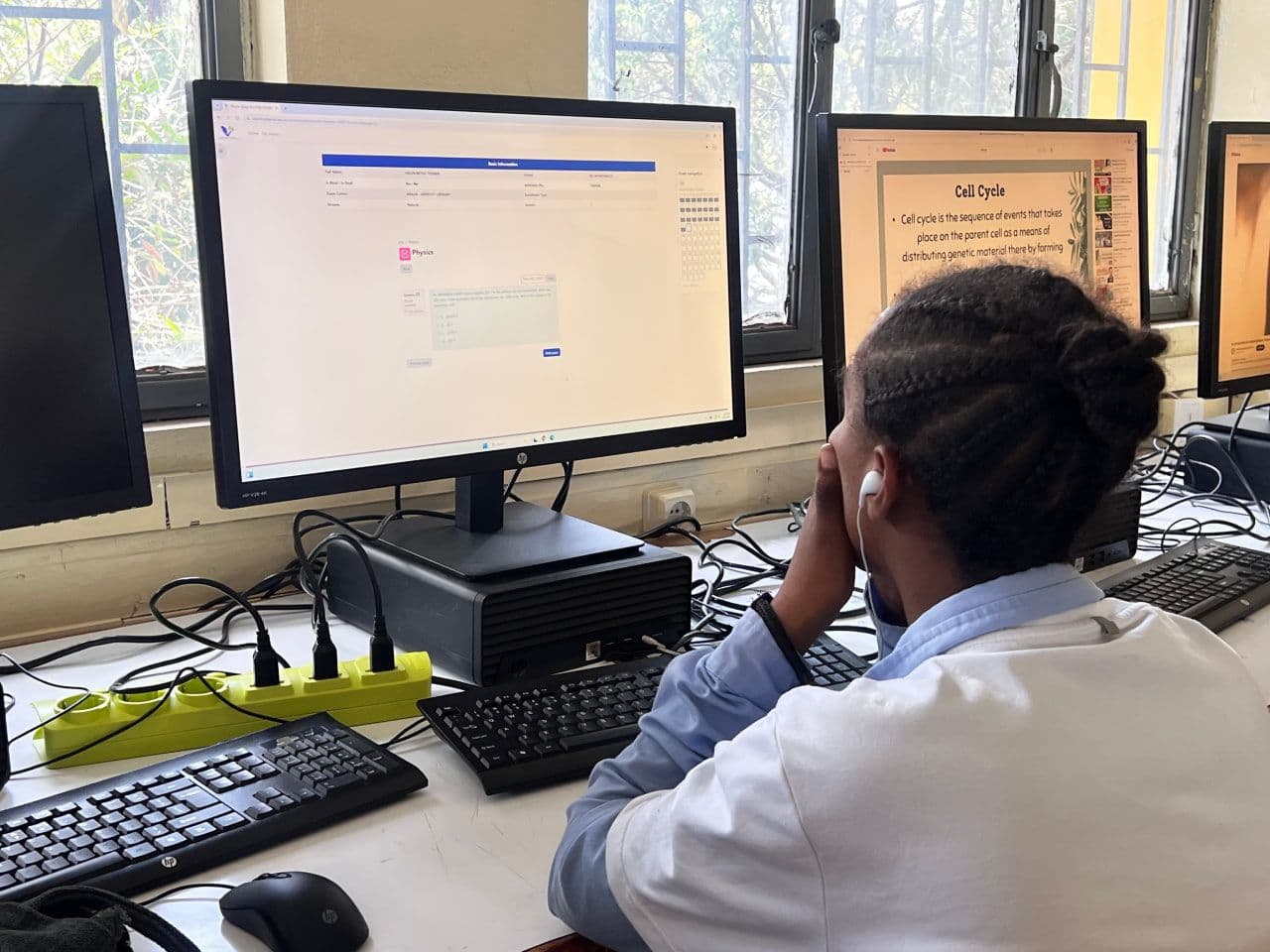

Ethiopia’s early efforts in digital education began in the early 2000s, when a handful of universities and select secondary schools introduced computers and basic IT infrastructure. Even though, for much of the next two decades, digital learning remained more aspirational than practical outside a few urban centres.

Recent years, however, have seen notable progress. Internet penetration in Ethiopia increased from the mid-teens in 2022–23 to around 21.3% at the beginning of 2025. Since the launch of the first Digital Ethiopia Strategy, aided by the entry of a second telecom operator, Safaricom Ethiopia. Ever since 3G coverage has expanded by 50 percent, while 4G access has grown eightfold. Ethio Telecom reported around 47 million data and internet users in 2025, up from 26 million five years earlier, while Safaricom’s network amassed 7.1 million active mobile data users by July of this year.

At the policy level, the Ministry of Education’s Digital Education Strategy and Implementation Plan (2023–2028) and the Digital Ethiopia 2025 initiative from the Ministry of Innovation have signaled a national intent to make technology a pillar of teaching and learning. Dozens of startups are experimenting with online content, learning management systems, and teacher-training platforms. Yet most activity remains concentrated in Addis Ababa and a handful of regional cities; rural learners are still far less likely to be online or to benefit from EdTech services.

Despite this policy interest and startup energy, the implementation of EdTech in Ethiopia remains fragmented. Entrepreneurs and developers often navigate a maze of government offices, education, ICT, and finance to certify content, register platforms, and secure recognition. Ministries and institutions often launch parallel initiatives without shared frameworks or interoperable data systems, resulting in duplicated effort and stretched resources. The ecosystem appears to be made up of bright pilots with no single gravitational center to pull them into scale.

So how can Ethiopia create a unified framework for cross-sector education technology policy? Such a framework would address fragmented government initiatives and promote a cohesive, whole-of-government strategy across ministries like Education, ICT, and Finance. It would also align infrastructure, digital content, and teacher training to maximize impact.

The October edition of EdTech Mondays Ethiopia, a monthly radio programme produced by Shega Media in partnership with the Mastercard Foundation, convened voices from government, academia and the private sector to unpack this question. Panelists were Serawit Handiso (PhD) (Lead Executive for Research and Community Engagement, Ministry of Education), Ephrem Tadesse (Founder & Chief Technical Officer, Bahirbits FinTech Solutions) and Yonas Fisseha (finance specialist in the EdTech sector).

Responding to the existing challenges, Serawit began by acknowledging both the potential of digital education and the persistent fragmentation of the system. “Education and research supported by technology can produce competent, visionary citizens,” he said, “but while we’ve worked for decades to improve equity, progress remains limited because many institutions still operate in isolation.”

According to him, the first challenge is cultural: shifting from an “I” to a “we” mindset. Institutions, he insisted, must move away from working independently and instead build mutually supportive systems. Serawit noted how the Ministry’s 2023–2028 strategy aligns with broader continental and national digital ambitions, but implementation will depend on coordination rather than additional plans alone. Another bottleneck, he noted, is the absence of an environment that facilitates information exchange and adapts to evolving technologies.

Echoing the same sentiment, Ephrem emphasized that resources, not just willpower, is key. “Technology is moving faster than our systems can adapt,” he noted. “Schools want to implement EdTech solutions, but the first question is always: with what money?”

Bahirbits’s founder emphasized that Ethiopia’s regulatory and financial institutions need to better grasp the scale of the challenge, noting that technology is evolving faster than the systems meant to govern it. The founder argued that progress will require investment not only in digital platforms but also in public awareness and digital literacy

Yonas framed the lack of a unified framework as a structural barrier to investment.

“It’s not just about policy or applications; it’s about building a system that works for every student. Funding will follow once people believe in the impact of EdTech.” he said, “but we need a single governing architecture so that funding routes, procurement rules and accountability mechanisms are clear.”

Panelists also pointed to infrastructure as a critical bottleneck. In Ethiopia, despite urban network coverage and fibre expansion projects, rural internet penetration remains very low. According to UNESCO’s recent assessment of Ethiopia, although mobile broadband coverage is high (94 percent of the population), only about 25 percent of Ethiopians are regular internet users, while a large portion of the population remains unconnected.

In practical terms this means many schools outside major cities still lack reliable electricity, stable internet, or sufficient devices for students and teachers.

The discussion also underlined the need for reliable data to inform policy and track outcomes. Universities could serve as pilots, generating evidence for the scalable implementation of these initiatives. Telecom providers like Ethio Telecom and Safaricom Ethiopia could supply usage data to support evidence-based planning. Yonas proposed creative financing mechanisms, saying “Even a one-cent levy on every phone call, or tax holidays for EdTech startups, could fund the digital transformation sustainably.”

As the conversation drew to a close, the consensus was clear: Ethiopia needs a unified, cross-sector framework for EdTech, one that aligns infrastructure, digital content, teacher training, and evaluation under a single national strategy. Such a framework would provide a coherent national vision, clearly defined governance, standards for digital learning, joint procurement processes, data protocols, teacher accreditation, minimum infrastructure requirements, funding channels, and monitoring systems.

In practice, this would integrate education strategy with ICT and telecom planning, ensuring that schools, start-ups, ministries, and funders operate from the same playbook. As Serawit put it, “The world is changing fast education, research, and jobs are being transformed by technology. To keep up, we must first identify what we already have, then refine and align it. Working with a shared vision, language, and purpose is more important than anything else.”

👏

😂

❤️

😲

😠

Partner Content

Partner Content is a collaboration between us and our partners to deliver sponsored information that aligns with your interests.

Your Email Address Will Not Be Published. Required Fields Are Marked *