Progress for 0 ad

Progress for 1 ad

Progress for 2 ad

Progress for 3 ad

Munir Shemsu

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Inclusive customer support is often overlooked as a determinant in fostering the adoption of digital financial services. Its impact becomes particularly pronounced for women in rural and semi-urban areas who have historically been underserved by Ethiopia's banking sector.

This piece is the latest from AKOFADA (Advancing Knowledge on Financial Accessibility and DFS Adoption), a project working to increase knowledge and transparency within Ethiopia’s DFS ecosystem.

____

On a late Saturday afternoon, I received a somewhat frantic phone call from a close friend. Following a “useless" interaction with a certain bank’s customer support agents, he was looking for help in making a digital payment. Poor communication lay at the heart of the conundrum as live customer agents kept denying the apparent changes to daily transfer limits. It turned out that my friend (a college graduate) had been struggling to move money out from his accounts at two local banks for an instant payment transfer. His attempts to find information from live agents at the 13 banks where he had accounts proved futile. Vague answers, endless waiting times on calls, and dismissive responses were all he could find.

While my friend ultimately decided to open his 14th bank account to avoid facing future challenges in making payments, I could not brush off the sense of unease I felt with the initial difficulties he faced. If a college graduate business owner did not have an easy time navigating payments on digital banking platforms, how can the larger general population be expected to easily adopt digital financial services? This begs the question of the primacy given to the design of customer support services in the development of digital financial products. With the continued role of banks as centers and enablers for digital financial innovation in Ethiopia, a closer look at their customer support is long overdue.

Experts say Ethiopia’s financial industry lacks responsive customer support capabilities tailored to addressing the immediate needs of consumers. Live agents available at most banks’ call centers provide little in terms of nuanced, inclusive, and real-time support to a customer base just starting to adopt digital financial services (DFS). Neither are Help & Support functionalities offered online much better, as they are often obscure with extremely limited capabilities.

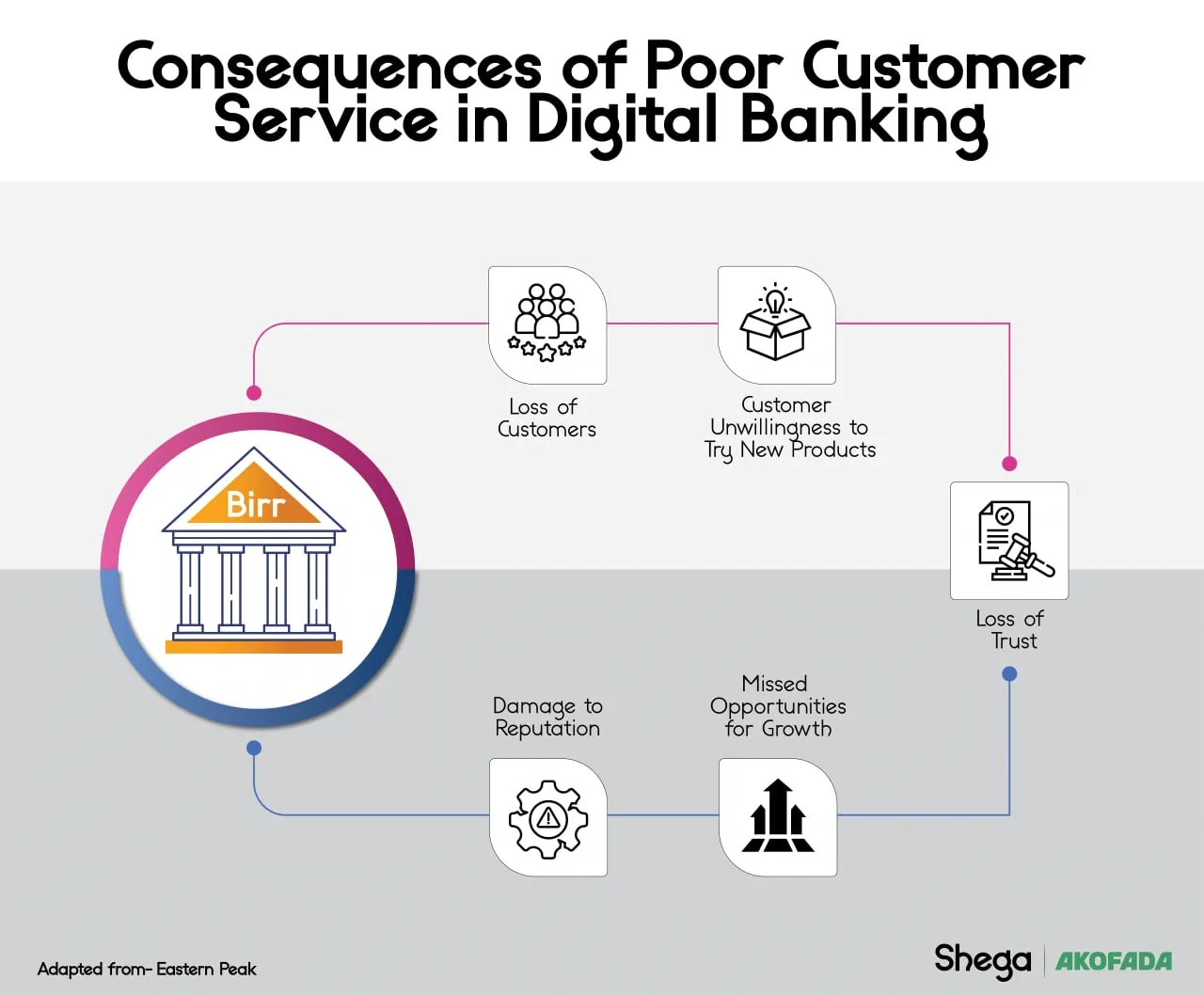

With trust being one of the determinants of DFS adoption, current practices in customer support, redress mechanisms, and communication strategies need to evolve. Be it a lack of national standards, the perceived absence of competitive advantages, or outright disregard for customer experience, Ethiopia’s banks are often accused of being unavailable when one needs them most.

A belated exploration into banking industry practices in Ethiopia and how certain exclusivist tendencies may have seeped into the DFS landscape could be insightful. Has there ever even been an incentive towards quality customer support?

Ethiopia’s nascent digital financial ecosystem is dominated by offshoots from the 30 traditional commercial banks, mobile money services through the state-owned Ethio Tel, and a few private companies providing niche products in specific subsectors. While public and private sector-led efforts to expand financial inclusion through the intense adoption of technology have increased the volume of digital payments to 1.5 billion transactions by 2023, it is still only a quarter of the target 6 billion set by the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) for 2026. A significant portion of the volume is also increasingly being contributed to by the mandatory use of mobile money services for fuel purchases, which added up to 197-billion-birr worth of transactions by March 2024, less than two years since deployment. Expansion of DFS products into rural and semi-urban regions is also quite limited, partly due to an underdeveloped digital public infrastructure and the shortage of nuanced customer outreach initiatives. While the telecom operator offshoot Telebirr has made significant headway with 47 million users, the country's biggest bank, the state-owned Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (CBE), has remained neck and neck with 10 trillion-birr worth of transactions through its digital payment infrastructure in the first eight months of the year. Albeit, a concentration of services in mostly urban areas to a majority male customer base.

Despite Ethiopia’s central bank targeting to include at least 70% of the adult population in the formal banking ecosystem by next year, some industry-rooted exclusivity hangups could hamper its objectives. Protracted redress mechanisms, inaccessibility of services, and a limited clientele, to name a few. The less than 30% of adult women with bank accounts further highlights the dismal track record regarding financial inclusivity in the analog banking sector. With women’s DFS adoption across all forms of digital financial services remaining at less than 25% as of 2023, an unfortunate parallel seems to be forming.

While most assessments of the landscape lock in on challenges of infrastructure, digital literacy, and regulation, the role of inclusive customer support is often overlooked. Issues of transparency, poor communication, distorted information, gender-blind design principles, and outdated customer service support are often understated hangups being carried over from the analog commercial banking sector into the digital realm.

For instance, a few weeks back I attempted to get some cash out from what turned out to be a faulty ATM, which debited my bank account despite withholding the money in the machine. I immediately called the four-digit customer service number on the machine and explained my situation to an agent, who seemed to be in a rush to get off the phone. Through a series of brisk remarks, he explained that the money was being held up by the other bank, rendering him "useless" in terms of immediate customer support. I had to physically visit a bank branch, fill out a form, and wait nearly a week for a little over a thousand birr. Despite my initial frustrations, I recalled figures from the recent report by the NBE, which highlighted the precarious liquidity and concentration risks faced by Ethiopia’s commercial banks. Not only were 56.3% of all deposits in the banking sector held by around 0.5% of depositors, but if 10 of the top depositors withdrew their money from all the banks, 18 of them would fall below the central bank’s minimum liquidity ratio.

Even though I managed to cushion my emotions in the figures, it led me down a deep rabbit hole attempting to understand how traditional banking practices, inclusive instant payment systems, and switch operators interplay to impact the accessibility of digital financial services in Ethiopia. A banking industry on shaky foundations deepens the inaccessibility of DFS if the help desk cultivates existing reservations in trying out new products.

The 2023 SIIPs report by AfricaNenda, which evaluates the inclusivity of Instant Payment Systems (IPS) in Africa provides some insight. The report reveals a marked increase in the number of IPS, with nearly 32 operational and around 17 in the early stages of development, albeit exhibiting lethargic progress in terms of inclusivity. One of the barriers indicated as restrictive to the wide adoption of digital payment systems was the challenge in effectively understanding scheme rules and performance data (value and volume). Transparency as a defining trait of regulators and payment service providers is cited as fundamental in driving the adoption of digital financial services. AfricaNenda’s report underlines the importance of having responsive redress mechanisms to build functional relationships between operators and customers in newly emerging payment systems. Ethiopia has a low percentage of its transactions processed through instant payment systems at 0.3% of the gross national income, facilitated solely through EthSwitch. While the national switch operator facilitated over 360, 000 interoperable transactions in 2022. it did not meet the minimum criteria of inclusivity to be ranked in AfricaNenda’s report.

A rather unsurprising conclusion when considering the overall confinement of financial services to a small segment of the country’s population.

Despite Ethiopia’s banking industry being open to private investment for the last three decades, bank loans were accessible only to around 0.3 percent of the above 120 million strong populace. Furthermore, only 45% of the population has bank accounts, with a mere 4% of the accounts holding more than 200,000 birr. Still, the smallness of the customer base has barely impacted the profitability of the banks.

Ethiopia’s financial industry managed assets equivalent to 42.1% of the country’s GDP in 2022 with a Return on Equity (RoE) of 25%. Impressive figures, if they were not so alarming.

An ecosystem of values marked by opacity, risk aversion, limited innovation, and asymmetry of information have blossomed in an industry closed off to competition. As is common in uncompetitive markets, Ethiopia’s banking industry has been characterized by bloated margins, exclusivity, and underwhelming customer relations. Very little incentive existed to compete in service provision, rendering customer support and redress mechanisms superfluous concerns.

During a family gathering a few months back, my aunt was telling the family of how someone called her from the bank with news of upgrades to her mobile banking service. She happily obliged to the step-by-step instructions from the caller, only to find the 7,000 birr in her account had vanished. As a savvy businesswoman who made her way through life leveraging her social skills, my aunt assumed it was a system error and reached out to the call center. They logged her report after she was forced to physically visit the bank. Her pleadings with the bank yielded only confusion as they referred her to law enforcement for follow-up on what was a bank impersonation fraud case. Frustrated by the sluggish response and what she felt was a tedious, convoluted bureaucratic procedure, she let the scammer off the hook, only retaining reservations about her digital banking activities.

Her story evoked other anecdotal scam experiences from family members with differing degrees of formal education who have all adjusted their behavior in the digital financial landscape. Some pull out their mobile money wallets only to make mandatory utility and fuel payments, while my aunt has appointed her 14-year-old son for all her digital needs. She has also limited her digital payments to nothing more than 1,000 birr. Being a proud single mother who rarely asks for help, my aunt did not appreciate the feeling of helplessness she experienced. The courteous customer support she had glimpsed when opening an account had vanished in her time of need.

However, my aunt’s experience barely sheds light on the repercussions most women in rural households could face if they were victims of a scam. With only 29% of total adult accounts being owned by women in Ethiopia and a significant portion being proxies for male counterparts, women have been largely left out by the banking system. The figures for DFS adoption don't seem to be faring better, with only 14% of the 90 million mobile money accounts in Ethiopia belonging to women as of December 2023. Furthermore, women account for only 22% of the user base across all forms of digital financial services. Redress mechanisms and a customer support practice incubated in an exclusive banking system could serve to further entrench the gender divide in the digital financial space.

If design principles with gender-intentional customer support features don’t become embedded into emerging financial products, the dangers of digital fraud could introduce a peculiar barrier to inclusive DFS adoption in Ethiopia.

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) has recently expanded the definition of digital fraud to include elements of spoofing (bank impersonation), fake financial products, social engineering, and phishing emails or SMS as incidents grew worldwide. This sentiment is echoed in the Global Anti-Scam Alliance's 2023 report, which indicates that around one trillion dollars was stolen from victims worldwide last year, exacerbated by inadequately supervised financial technologies.

The NBE’s report on financial stability reaffirms the global trend as bank frauds and forgeries, including false texts and calls, withdrawals using stolen ATM cards, false financial instruments, and embezzlement, doubled to one billion birr in 2023. Responsive and accessible customer support systems will decrease exposure to scams and mitigate financial impact. Vulnerabilities become magnified as poor customer support leaves a vacuum where distorted information sips in. Poor communication practices create an ideal setting for attackers to exploit, impacting lower-income households the most.

With potential avenues of attack expected to naturally increase with the advent of technology, the ease and availability of response mechanisms provided by banks go a long way in determining the adoption of inclusive digital financial services. Women will likely be disproportionately excluded in rural Ethiopia if distrust of digital products gets entrenched with higher instances of fraud. A backdrop where only 10% of rural women have formal financial accounts highlights the depth of the gender gap.

In a country like Ethiopia, where most household finances are controlled and managed primarily by men, scam-induced losses could serve to further entrench gender biases. This becomes significantly pronounced in rural and semi-urban areas of Ethiopia, where communal values become established from the anecdotal experiences of members. The social network effects on adoption cannot be understated. It becomes quite unlikely for women to start using a digital financial product if word gets around that it entails financial loss.

Furthermore, confidence in the integrity of financial service providers is intimately tied to the ease with which support and response is provided during setbacks.

The interplay between gender roles, customer support, and digital fraud needs to be embedded in the design of DFS products to foster inclusivity.

Effective decision-making can only come about through detailed analysis of comprehensive data available on any issue. Gender disaggregated data collection on incidences of digital frauds, response time from DFS providers, and trends in financial behavior after an incident are foundational. This data can be leveraged to identify the degree to which DFS adoption is being hampered by the confluence of forces etched in an archaic financial landscape. Projects targeted at mapping out the relationships could serve as a stepping stone towards services and products cognizant of the prevailing hangups.

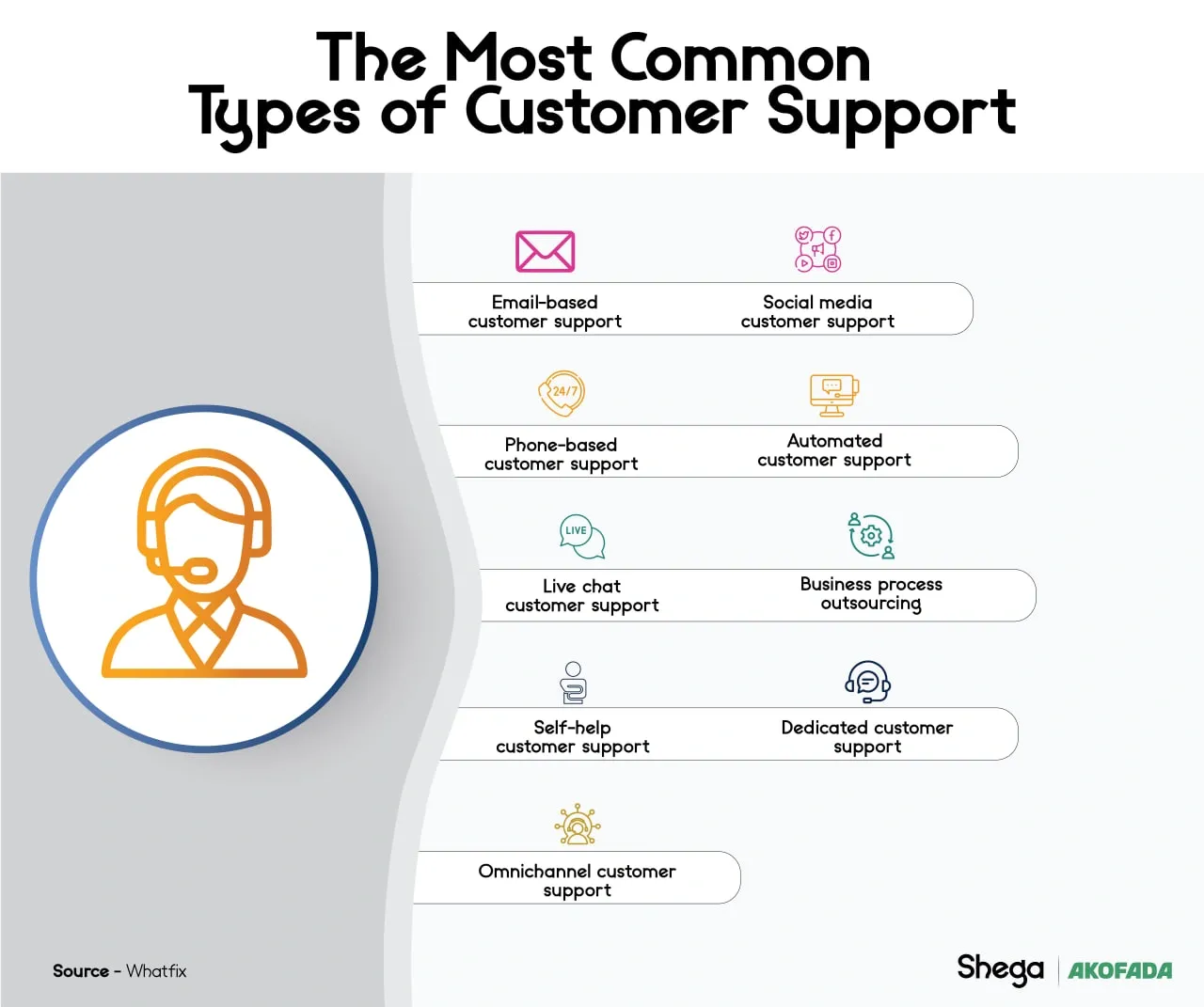

Another possible area of exploration can be towards improving customer support practices in existing financial institutions to instill a culture of customer centricity and gender intentionality that spills over into the digital space. A banking industry that has flourished by catering to a small fraction of the populace needs to invest heavily in addressing pragmatic communal needs. Improved response mechanisms, effective complaints, and redressal mechanisms accessible in multiple local languages with dedicated customer- and agent hotlines could go a long way. Targeted investments by the banks to increase the number of female agents would make marked improvements in creating social links with local communities. A trusted female intermediary can create confidence for exploring new DFS products and establish a mechanism of support during potential fraud attempts while increasing overall literacy levels.

While the benefits of investments in fraud monitoring systems, increased automation, and robust analytics will accelerate general cyber security, community-based programs to expand financial and digital competency are crucial.

Investments in the digital public infrastructure need to include design principles customizable to the unique communal and financial backdrop of Ethiopia. Advancements in mobile penetration rates, internet coverage, and telecommunication infrastructure have to be complemented by headways in working cultures. Embedding inclusivity across genders, economic classes, and education status by accommodative design principles, updated working practices, and reimagined customer service procedures are crucial for increasing financial inclusion in Ethiopia.

A comprehensive evolution in customer support practices as a critical lever for driving inclusive DFS adoption within Ethiopia is critical. Multidisciplinary contributions that take into account the unique anthropological and economic landscape will prove pivotal for driving DFS adoption.

👏

😂

❤️

😲

😠

Munir Shemsu

Munir S. Mohammed is a journalist, writer, and researcher based in Ethiopia. He has a background in Economics and his interest's span technology, education, finance, and capital markets. Munir is currently the Editor-in-Chief at Shega Media and a contributor to the Shega Insights team.

Your Email Address Will Not Be Published. Required Fields Are Marked *