Progress for 0 ad

Anteneh Tesfaye

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

While Ethiopia draws lessons from the financial inclusion successes of its neighbors, we need to ask bigger questions. How should we tailor financial solutions to truly resonate with the unique socio-economic fabric of Ethiopia?

Catch up with the first of many monthly analysis articles by AKOFADA (Advancing Knowledge on Financial Accessibility and DFS Adoption), a project that is working to increase the knowledge base of Ethiopia’s DFS ecosystem.

_________

In 2016, I found myself along with my five Ethiopian teammates, stuck on a road leading from Entebbe International Airport, on the shores of Lake Victoria, to Kampala, the capital of Uganda.

The reason? We were attending a regional youth leadership conference. This trip marked my first visit to another African country, and my curiosity was piqued. Amidst the traffic congestion, a few things became evident.

The roads appeared much narrower than those I was accustomed to back home. Motorbikes, locally known as Boda Boda, swarmed the streets, outnumbering four-wheelers—an unusual sight for someone from Ethiopia.

Fast forward to August 2018, and I am in Nairobi, Kenya, walking down the road from my temporary apartment to Africa’s Talking Kenya office, a short five-minute journey. Tasked with helping Africa’s Talking, a communication and payment solution provider, launch and grow in Ethiopia, my mission in Nairobi was to understand how things operated at the company’s headquarters.

Much like my experience in Uganda, the roads in Nairobi felt narrower and predominantly one-way, with motorcycles being common in sight.

In contrast to Uganda and Kenya, Addis Ababa and much of Ethiopia rely less on motorcycles and narrow streets and more on wider roads and cars. This difference in transportation modes can be partly attributed to Ethiopia’s unique historical and socio-political context.

However, my most significant learning came from observing and interacting with professionals and residents in Nairobi. Many owned or had inherited land outside the city, maintaining ancestral connections or a rural base despite their urban lifestyles. This reflection of the deep-seated value of preserving familial and rural ties amidst urbanization struck me. It prompted me to consider if a similar sentiment exists among Addis Ababa’s urbanites, inviting contemplation on the cultural nuances shaping behaviors and choices in urban Ethiopia, including financial service.

This journey through the roads of Uganda and Kenya, along with my experiences in Ethiopia, underscores a critical point: no two countries are the same, even in Africa and East Africa.

The above two East African countries I visited in the past surely have similar things. First, they both made significant strides in financial inclusion over the past decade. Particularly, Kenya is viewed as a model for achieving financial inclusion through mobile technology, showcasing a leapfrogging success story.

In contrast, Ethiopia embarked on this path somewhat later. But the country is now full of action, with numerous activities supporting and enhancing the financial ecosystem.

These efforts, driven by both service providers and facilitators, signal a growing recognition of the critical role of financial inclusion in countries’ journeys of transformation. As Ethiopia treads this path, it draws inspiration from its neighbors’ successes.

However, these efforts often seem to operate without full recognition of the distinct paths countries go through, tending towards a strategy of imitation from models like Kenya’s rather than tailoring unique solutions that reflect Ethiopia’s unique socio-economic landscape.

Drawing on this notion, we can set the stage for a deeper dive into the critical question of how we should look at and assess Ethiopia’s quest to bring financial services to the majority.

Before we delve into details, let’s first establish a foundation and conduct a reality check. Financial inclusion is a word that gets thrown around a lot these days. It encompasses ensuring that all individuals and businesses, regardless of their standing, have access to basic and affordable financial services, such as payments, credit, savings, and insurance, which are fundamental to participating fully in the economy.

The concept of financial inclusion has emerged as a cornerstone for economic and social development. But there are also those who argue that economic development is a prerequisite for financial inclusion.

The academic world provides two theoretical frameworks to describe the relationship between financial development (including financial inclusion) and economic growth: the demand-driven hypothesis and the supply-leading hypothesis.

The supply-leading hypothesis posits that providing financial services spurs economic growth by equipping individuals and businesses with the resources needed for investment and expansion, effectively acting as a catalyst for economic activities. On the other hand, the demand-driven hypothesis suggests that economic growth creates a need for financial services, with the development of the financial sector being a response to increased economic activities and the rising financial needs of a growing economy.

A study by Tekilu Tadesse and Jemal Abafia, ‘The causality between Financial Development and Economic Growth in Ethiopia,’ using data from 1975–2016, supports the ‘supply-leading’ hypothesis, showing that financial development positively impacts Ethiopia’s economic growth both in the short and long term, highlighting the critical role of financial sector advancements in driving economic progress.

Many initiatives aimed at promoting financial inclusion in Ethiopia, whether spearheaded by governmental bodies or international development organizations, appear to be predicated on the principles of the supply-leading hypothesis.

In reality, the relationship between financial inclusion (and, more broadly, financial development) and economic growth is complex and can involve elements of both hypotheses. Effective strategy-making often seeks to leverage the interplay between supply and demand, recognizing that:

While acknowledging the interplay, let’s look at where we are. Ethiopia stands at a critical juncture in its journey towards comprehensive financial inclusion. Despite considerable strides in recent years, propelled by policy reforms and consolidated efforts, the Ethiopian financial ecosystem faces unique challenges and opportunities in its quest to provide universal access to financial services.

Recognizing the importance of having a consolidated approach towards financial inclusion, Ethiopia put forward the first National Financial Inclusion Strategy (2014–2020), followed by an updated strategy covering 2021–2025. The National Bank of Ethiopia is focused on achieving a significant milestone: ensuring that 70% of adults have bank accounts by 2025. One of the pillars of recently introduced Ethiopia’s National Bank New Strategic Plan 2023–2026 policy is also ensuring financial inclusion, deepening, and digitization.

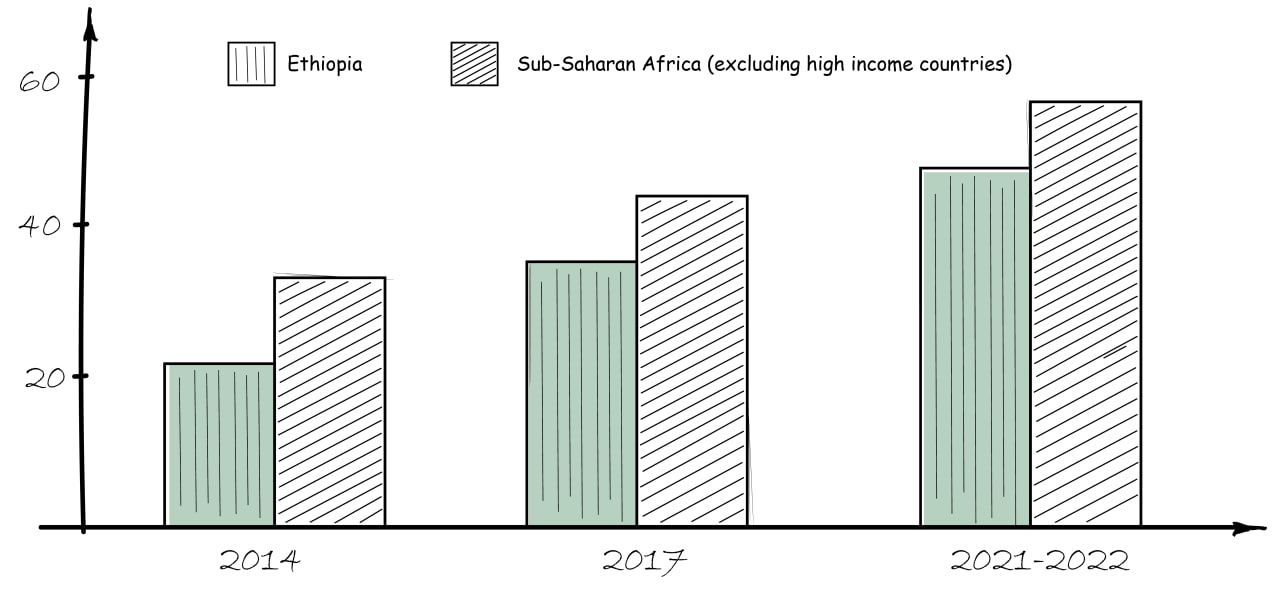

Ethiopia’s latest financial inclusion figures come from the Findex 2022 report. The expansion of account ownership in the country has been significant, nearly doubling from 22% in 2014 to 46% in 2022. Although the percentage of Ethiopian adults with a bank account has seen continuous growth since 2014, it still trails behind the Sub-Saharan Africa average of 55%.

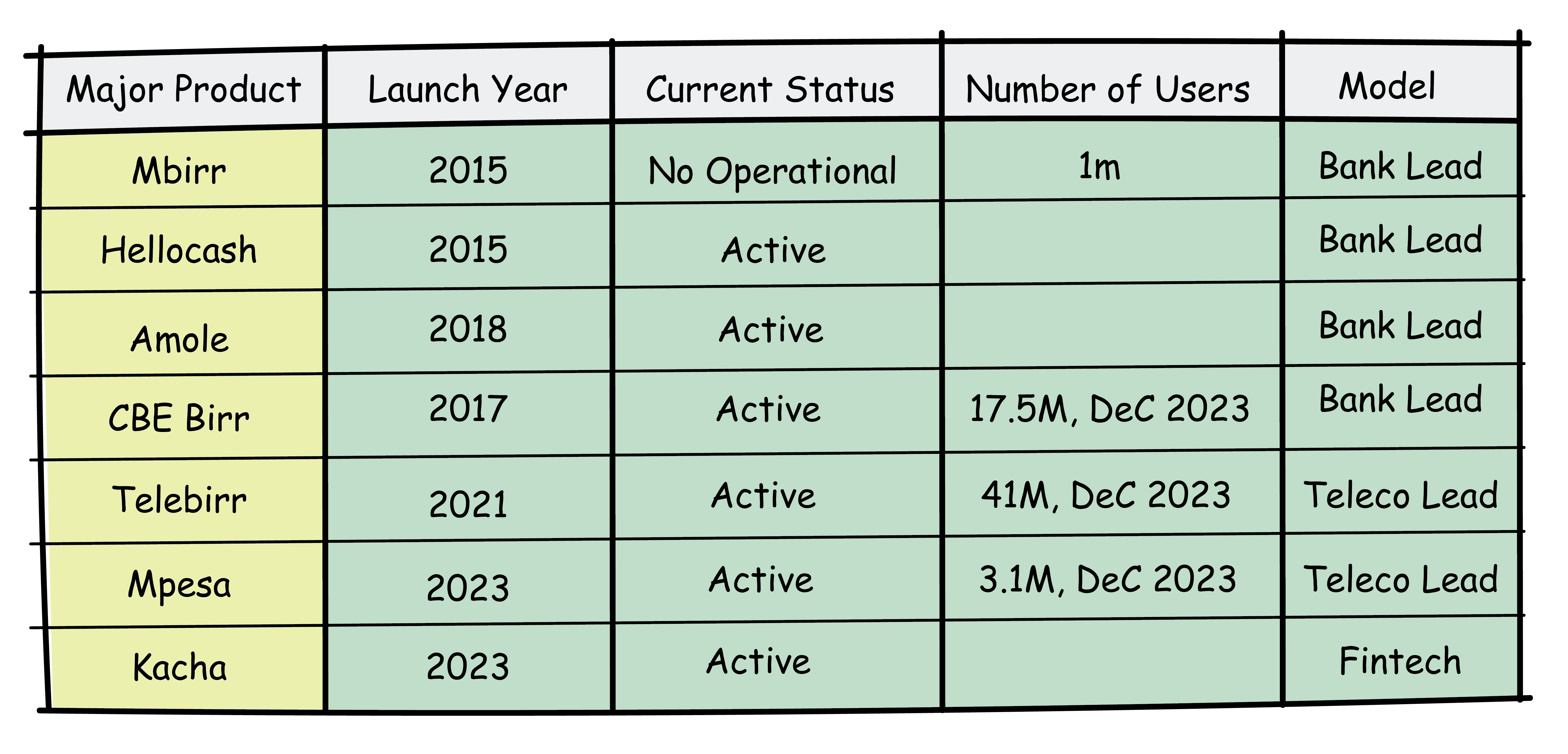

For a comprehensive understanding of the financial landscape, it’s also crucial to consider the developments in 2022 and 2023. The continued growth of Ethio Telecom’s Telebirr and the introduction of Safaricom’s Mpesa to the Ethiopian market are noteworthy.

The self-reported numbers of Telebirr, Mpesa, and CBE Birr mobile money accounts are said to be nearing 55 million by the end of December 2023, illustrating a significant uptrend in digital financial inclusion in the country. However, while interpreting this data, it’s advisable to exercise caution.

Looking deeper beyond numbers, a recent brief by the United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF) that leveraged the World Bank’s 2022 Global Findex Database provides insightful summaries on the status quo of financial inclusion in Ethiopia. The analysis explores themes of access, usage, and financial health, helping us map Ethiopia’s progress and identify key priorities for the future.

In light of Ethiopia’s unique socio-economic landscape and the complexities surrounding its financial inclusion journey, a structured analytical approach is paramount. Introducing the decision tree approach, a strategic framework developed by the Center for Global Development to dissect and overcome the barriers to financial inclusion.

The decision tree methodology, inspired by the famous Growth Diagnostic framework, offers a systematic way to identify the binding constraints to financial inclusion.

The approach employs a top-down analysis. The tree starts by defining constraints on supply (service provider-driven causes) and demand (user-driven causes). It then moves to high-level potential causes under each before going to a more detailed constraint.

To accurately pinpoint the pressing constraints, the decision tree provides a framework for analysts to utilize a combination of observed data, shadow prices, quantities, and a comprehensive set of indicators.

When it was applied to the Ethiopian case in 2021, it revealed that supply-driven barriers, particularly institutional issues like the limited capacity of regulators and a reluctance to foster competition, are key constraints, creating a monopolistic environment that leads to high costs and limited availability of digital payment services.

However, since 2021, significant progress has been made in addressing some of these pain points, such as market structure (e.g., licensing for telecom and non-telecom mobile money services like Mpesa) and improving digital infrastructure (e.g., advancements in interoperability and telecommunications liberalization).

This progress opens avenues to explore demand-driven constraints (such as trust, socio-economic realities, and financial literacy) and other supply-side challenges (including understanding customer behavior, identifying needs, and enhancing the capacity of financial institutions).

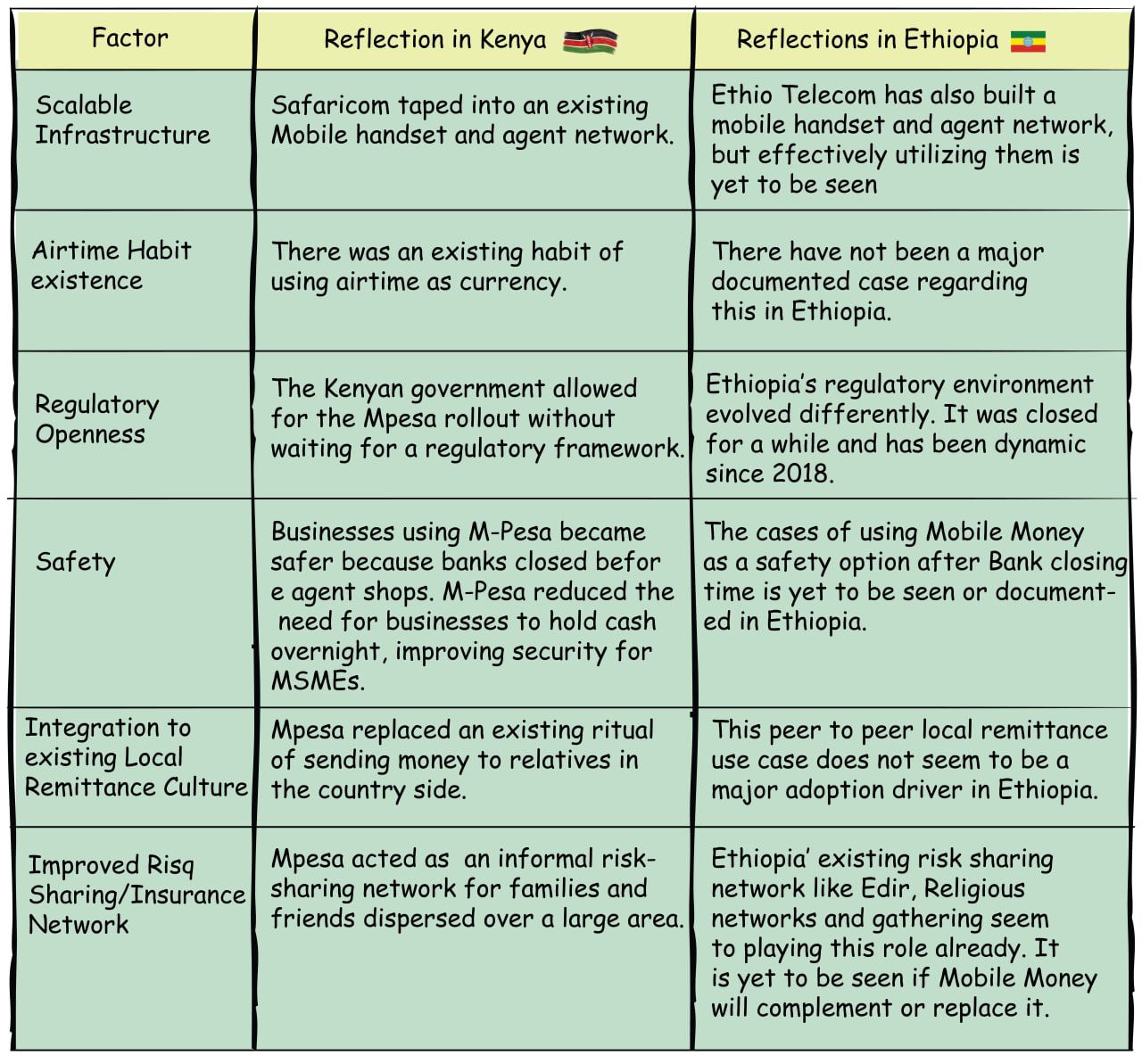

My observation of the urbanities in Nairobi becomes particularly relevant when considering the story of M-Pesa, a mobile money service that has significantly influenced financial inclusion across Kenya and beyond.

The inception of mobile money systems, starting with the Philippines in 2001 and notably M-Pesa in Kenya in 2007, marked a significant shift in how financial transactions are conducted.

M-Pesa, initially an experiment for microloan disbursements and payments via mobile phones, quickly became a tool for sending money among family and friends over large distances.

M-Pesa’s success was not merely a result of technological innovation but also of its alignment with the cultural practice of supporting dispersed family networks. This highlights the importance of cultural compatibility in financial technology adoption.

M-Pesa’s story is one of leapfrogging in the Global South, representing a rare full-circle success story in financial technology adoption that we can evaluate comprehensively. It prompts an exploration of all the factors contributing to M-Pesa’s success and whether these can be replicated or adapted in Ethiopia’s quest for financial inclusion.

Looking at the factors contributing to M-Pesa’s success, it’s clear that its triumph in Kenya was the result of a confluence of unique environmental, cultural, and regulatory conditions.

Kelsey Piper, writing for VoX about Mpesa, put it this way: “M-Pesa’s seemingly magical success wasn’t a product of M-Pesa alone. It was a combination of the right technology, at the right time, rolled out in the right way, with the right decisions from the Kenyan government to allow the system without applying onerous regulations or high government fees on every transaction. “

Reflecting on Ethiopia, one question then arises: Why do we seem so intent on imitating M-Pesa in Ethiopia? Our discussions and narratives often lean heavily on replicating models that have shown success in other countries, potentially overlooking the rich tapestry of Ethiopia’s own socio-economic and cultural context.

Ethiopia, with its diverse cultures, languages, and economic practices, offers a fertile ground for innovation that is deeply rooted in the needs and behaviors of its people.

In essence, while the allure of replicating a successful model like M-Pesa is understandable, it is crucial for Ethiopia to chart its own course in the realm of financial inclusion.

In this journey towards financial empowerment, Ethiopia doesn’t just need to replicate M-Pesa; we need to find our own ‘M-Pesa,’ a solution that mirrors our unique identity, challenges, and aspirations as Ethiopians.

This requires a balance between learning from global successes and innovating locally to address the specific needs and challenges of the Ethiopian population, guided by a framework that emphasizes innovative solutions to financial access.

This approach invites us to rethink financial inclusion beyond mere technological adoption, considering the broader cultural, economic, and infrastructural contexts that influence how financial services are developed, deployed, and adopted by the populace.

Achieving financial inclusion requires systematic and cultural change. Such changes can only occur with a nuanced understanding of various markets, systems, and cultural situations.

______

This article is published by AKOFADA (Advancing Knowledge on Financial Accessibility and DFS Adoption), a project that aims to improve financial inclusion through digital financial services by creating the same operating knowledge base for stakeholders in the sector, supporting the provision of relevant services to end users, and creating trust and confidence in the population about using digital financial services while also highlighting and assessing systemic issues.