Progress for 0 ad

Progress for 1 ad

Progress for 2 ad

Progress for 3 ad

Munir Shemsu

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

AI could be Ethiopia’s next engine of inclusion. But only a handful of players, like Kifiya, are deploying AI to unlock credit and inclusion. With smarter credit scoring, multilingual banking, and AI-powered agricultural finance, financial institutions could reach millions of unbanked citizens.

Data fragmentation, weak infrastructure, and scarce human capital stall momentum. Yet these are merely speed bumps, and quick adoption could spawn revenues to iron out flaws while vaulting inclusion.

This article is an output of AKOFADA (Advancing Knowledge on Financial Accessibility and DFS Adoption), a project working to increase knowledge and transparency within Ethiopia’s DFS ecosystem.

Four years ago, I stumbled upon Dawn AI, a compact mobile app that generates images from user prompts. It felt like rubbing Aladdin’s lamp: every flight of fancy materialized in seconds. As I delved deeper into artificial intelligence tools, I became convinced of an economic and political upheaval on the horizon: intuitive, personalized multilingual agents that would equip millions with skills, tools, and information to escape poverty. I envisioned surging agricultural yields, built-in financial transparency, and clear pathways out of deprivation.

But over the years, the dividends from the ‘revolution’ in Ethiopia have felt underwhelming at best, even corrosive in spots. News publications and social media now teem with identical cadences, em dashes (—), and the word “landmark.” Nuance has yielded to bluster; a cadre of ChatGPT consultants has emerged.

Admittedly, AI is reshaping industries in wealthy nations. Coders draft lines with less drudgery, accountants escape number-crunching tedium, and lawyers have found an even faster way to make money. But if you believed the frenzied initial hype, AI should have started tying our shoes, running our businesses, and solving world hunger by now, as Paul Hliviko recently wrote in the Harvard Business Review. The most profound breakthroughs remain bunkered in multinationals, private labs, and military vaults. For much of the Global South, the windfalls amount to slicker content creation, schoolwork, and quicker emails, perks mostly for white-collar workers and urban youth, while hundreds of millions in rural and peri-urban zones remain excluded from yet another industrial revolution.

Ironically, unless we are waiting for the rise of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) to recommend ways of rewiring the global financial architecture, the absence of deep, inclusive financial networks will remain one of the biggest barriers to escaping poverty. Access to affordable credit, insurance, savings, and investment tools still determines economic mobility. In a country like Ethiopia, where only 49% of the adult population has bank accounts and less than half a million have accessed credit through legacy financial institutions, the stakes could not be higher.

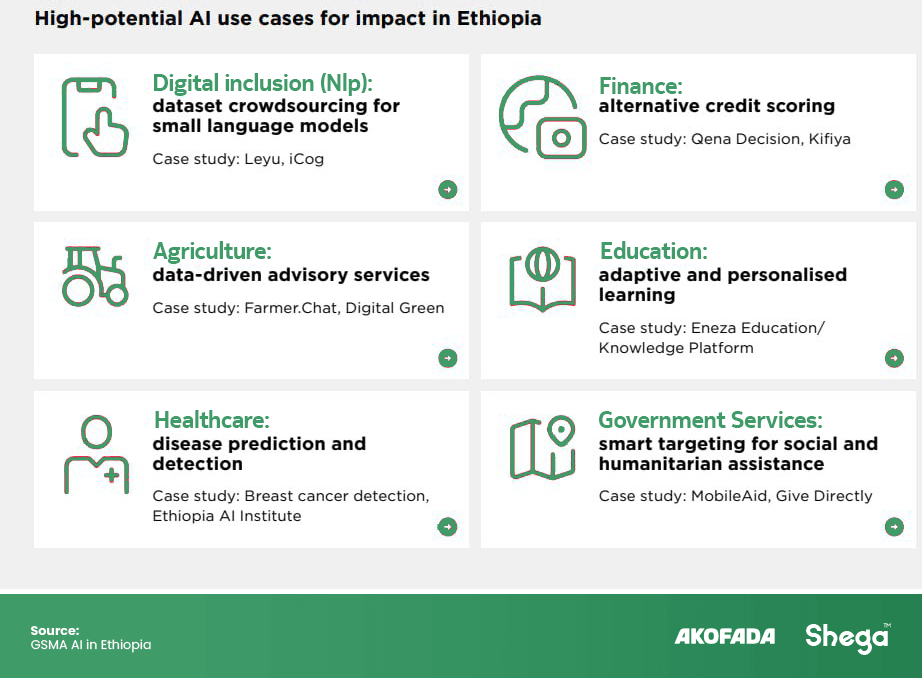

AI’s promise lies in helping close this gap. From credit scoring models that draw on alternative data to personalized advisory chatbots and voice-based banking, intelligent systems can expand financial access for millions. Yet for now, millions of farmers remain uninsured, underbanked, and unable to invest in technology or secure reliable suppliers. We need to reconsider development models that solely rely on GDP growth, particularly with the availability of transformative digital tools. Policies and products to elevate Ethiopia’s nearly 86 million multidimensionally poor cannot ignore AI.

The country’s strides in digital financial services (DFS) over recent years could multiply exponentially with AI. By 2028, some 50 million Ethiopians are projected to have mobile internet connections, alongside nearly 90 million registered mobile money accounts. Ripe opportunities await to broaden financial inclusion and ignite meaningful economic development.

But, to date, just a handful of institutions have even explored DFS use cases that leverage the expansive powers of AI.

Digital transactions grew by 129% year-on-year to reach 12.5 trillion Birr in the last fiscal year, yet only one Ethiopian fintech has harnessed this tide for fresh products.

In January of 2022, Kifya Financial Technologies partnered with the Cooperative Bank of Oromia (COOP) to launch a digital lending product dubbed Michu. A non-collateral-based credit product leveraging AI, designed to cater to Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs). Adoption was quick, as three years down the line, over 50 billion Birr was disbursed to around half a million MSMEs.

Five more banks would go on to adopt Kifiya’s AI platform dubbed Qena, including the Sharia-compliant ZamZam Bank. A few more banks are also in the pipeline, waiting to incorporate the AI platform into their lending facilities.

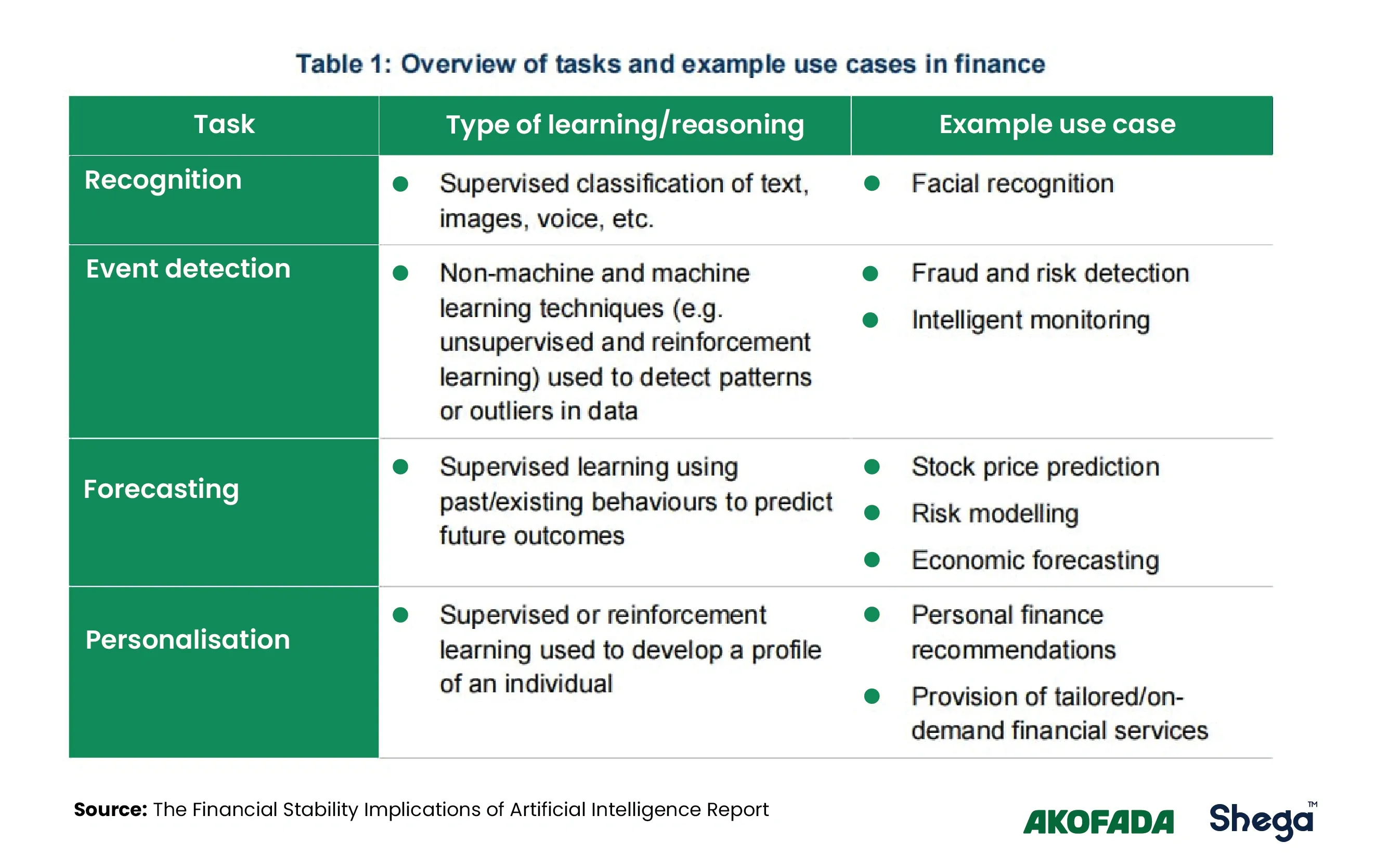

While very limited formal data on MSMEs exists in Ethiopia, Qena leverages AI and alternative data, turning non-traditional information into credit insight. Instead of relying on full financial statements and collateral, lenders analyze digital transaction flows, mobile usage patterns, geolocation stability, repayment history on starter loans, and other behavioral signals.

Kifiya further expanded its AI-based credit services, managing to disburse over 730 million Birr via input credit to farmers. The fintech firm has maintained a steady pace of innovation, most recently providing AI-powered remote know-your-customer service solutions that can work even in areas with patchy internet connectivity. Unfortunately, Ethiopia’s story with AI innovation delivering financial inclusion largely halts with Kifiya.

The few separate AI adoption use cases within the financial sector have been isolated and focused on in-house operational updates. As part of its attempt to tackle fraud and illicit financial flows, the National Bank of Ethiopia has said it has deployed AI tools over the past year. A few banks have also incorporated AI to help facilitate branch services. Ethio telecom also deploys a chatbot of middling prowess for queries. While these deployments could yield much-needed improvement in existing financial services, they fall far short of breaching financial exclusion walls. Even banks that have significantly upscaled their digital banking wings have yet to capitalize on the troves of data using AI.

Any mature DFS ecosystem has to start by first delivering financial access points, and Ethiopia is no different. Traditional financial access points like banks entail significant overhead costs alongside existing physical and administrative infrastructures to accommodate them. This has historically pushed bank branches to converge in capital cities and a few urban areas. Ethiopia exemplifies this phenomenon, with nearly a third of all bank branches being in Addis Ababa. However, AI-driven ecosystems can help overcome legacy infrastructure constraints through a mobile-first approach, supported by voice-based user interfaces and multilingual user experience (UX) designs.

Even the costs of buying a mobile phone could be anchored in a long-term financing arrangement that utilizes alternative data. The digital footprint that begins to form at the moment of onboarding could then be transformed into an ingredient for other DFS, like credit or insurance.

For a country like Ethiopia, where close to 70% of the labor force is engaged in agriculture, AI could bring about an unprecedented surge in the type and quality of potential DFS services. Apollo Agriculture, an ag-tech company operating in Kenya and Zambia, has demonstrated a varied set of use cases for smallholder farmers using AI. The company offers a comprehensive package of services, including credit, high-quality inputs, agricultural advice, and risk mitigation solutions, such as crop insurance. The platform uses satellite data, agronomic machine learning, remote sensing, and mobile technology for credit assessment.

Loan repayment schedules aligned with sowing and harvesting cycles have enabled Apollo’s services to reach more than 400,000 farmers. By accessing high-quality inputs through credit solutions, the farmers were also able to produce around two and a half times higher yields than the national average. Tailored interest rates, quick conversion times, and seamless user experience have proven to be highly impactful. Apollo, backed by $65 million in funding, shows what’s possible, though Ethiopian peers rarely, if ever, receive such capital. Local banks could pivot to rural diversification, with AI curbing legacy-cost bloat. Fewer branches, yet more services and clients.

In banking, AI is no longer optional but existential. The global banking sector was estimated to spend over $73 billion on AI technologies by the end of 2025, marking a 17% year-on-year increase. AI is expected to contribute $1.2 trillion to the global banking industry by 2030. Opportunities to improve profitability through revenue generation, cost reduction, risk management, and productivity gains are driving adoption.

Ethiopia’s annual revenue-obsessed banks risk obsolescence against global rivals without evolution. Initial AI tweaks to operations could build chops, spur income, and fund inclusive DFS, all while slashing fraud, which siphoned 1.3 billion birr last year. It is almost a guarantee that foreign banks entering Ethiopia won’t be eyeing market share via branch expansion but rather technology.

But it is not just the banking sector that would benefit from AI integrations. Ethiopia’s underdeveloped insurance sector, which relies on motor and marine insurance for nearly three-quarters of its revenue, would experience unprecedented gains with AI adoption. Credit underwriting, insurance pricing, and customer service are receiving a thorough makeover with AI in most mature financial markets.

Powered by data from DFS providers, Ethiopia’s insurance industry might finally be able to conduct risk assessment on previously unimaginable levels with AI. The prospects of microinsurance services for millions of households or even basic health insurance through analysis by AI tools and integrations into existing digital systems are all within reach.

To accelerate this, Ethiopia’s National AI Policy, approved in 2024 and operationalized via the Ethiopian AI Institute in 2025, provides a scaffold. Policymakers could layer on DFS-specific incentives: tax breaks for AI R&D in ag-lending, mandates for algorithmic audits in credit scoring, or public sandboxes for 10-15% of transaction data. Such levers, drawn from GSMA’s 2025 playbook, could fast-track inclusion to the Digital Ethiopia 2025 target of 70% of adults having a formal bank account.

An ocean of partnerships, butterfly effects, and unprecedented use cases for Ethiopia’s DFS ecosystem lies ahead with AI adoption. A comprehensive assessment of current opportunities and prevailing handicaps is, at the very least, a worthwhile strategic gamble.

Still, AI’s promise in DFS is double-edged. While it unlocks credit for the unbanked, unchecked models risk entrenching biases, sidelining women farmers (40% of the labor force), or fueling fraud in a sector losing billions to scams. The 2025 State of AI in Africa report flags cybersecurity, human capital gaps, and discriminatory algorithms as top threats, potentially widening inequalities if data silos persist. Mitigation demands ethical guardrails: federated learning (a privacy-preserving approach to artificial intelligence that trains models across many devices or servers without transferring users’ personal data to a central location), bias audits in platforms like Qena, and perhaps AU-aligned standards to ensure AI amplifies, not erodes, equity.

Regardless of how many ideas, potential use cases, or transformative prospects there may be, AI adoption into Ethiopia’s DFS ecosystem still faces crippling constraints. Underdeveloped data ecosystems, lack of investments into local cloud/HPC capacity, and scarce human capital, to name a few. AI application diversity will evidently take time to mature across sectors. But for DFS, there is enough data (both financial and alternative data), cloud capacity, and talent to see immediate gains.

Telebirr alone logs four years of credit, spending, and micro-investment data from 55 million users. Following the progress in the integration of financial services with the Fayda digital ID, it has become easier than ever to track the financial records of Ethiopians. The Community-Based Health Insurance scheme spans 40 million citizens’ records. Furthermore, startups like Hasab AI have made significant headway in tackling the language barrier with tools capable of capturing phonetic nuances in local languages. Combining these and other similar resources could prove to be powerful.

Ethiopia does not necessarily have an insurmountable shortage in data sets but rather faces challenges around data quality. Fragmentation of data also poses a significant hurdle to properly encoding and analyzing the available information. Yet these are speed bumps against AI’s momentum. Adoption could spawn revenues to iron out flaws while vaulting inclusion. A roadmap forward might include hybrid skilling hubs, university-fintech apprenticeships, and south-south pacts, the exchange of resources, knowledge, and technology between countries of the Global South. Kifiya’s IFC tie-up exemplifies scalable collaboration.

Ethiopia’s financial players must infuse AI deeply to serve clients and even their own shareholders. Evolutions demand service refreshes and routine overhauls. Integration speed will redraw the map. But delaying it will mean continued setbacks for millions’ access to critical financial services.

In synthesizing these dynamics, the trajectory of AI in Ethiopia’s DFS ecosystem emerges not merely as a technological inflection but as a pivotal vector for recalibrating socioeconomic architecture. Yet realizing this demands a deliberate fusion of policy foresight, public-private synergies, and ethical guardrails to mitigate asymmetries in data sovereignty and algorithmic equity. For scholars and practitioners alike, the imperative is clear: Harness AI not as an imported panacea, but as an endogenous catalyst, forging pathways where financial depth amplifies human agency and sustainable prosperity.

👏

😂

❤️

😲

😠

Munir Shemsu

Munir S. Mohammed is a journalist, writer, and researcher based in Ethiopia. He has a background in Economics and his interest's span technology, education, finance, and capital markets. Munir is currently the Editor-in-Chief at Shega Media and a contributor to the Shega Insights team.

Your Email Address Will Not Be Published. Required Fields Are Marked *