Progress for 0 ad

Progress for 1 ad

Progress for 2 ad

Progress for 3 ad

Etenat Awol

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Two weeks ago, Ethiopian Electric Power (EEP) announced a new, multi-phase tariff structure for Bitcoin miners. Scheduled to take effect in the coming month, the framework will replace the flat rate of around $0.0314 per kilowatt-hour with a more complex system that incorporates time-of-use pricing and an availability-based rate.

The increases are steep: close to 30% in December 2025, followed by 24% in July 2026 and 28% in July 2027. The move comes a few months after the state-owned power provider announced it would no longer issue new permits for bitcoin miners.

The notice landed abruptly, and while some mining companies are still hoping for negotiations, the announcement has sent shockwaves across the industry, with some weighing the possibility of shutting down or selling facilities to relocate to markets with more predictable regulatory environments.

For Bitcoin miners, electricity is the single most important factor in determining their operating costs. Power expenses gobble up around 60% of total revenue, and in some cases, that could goes up to 70%.

Following the new tariff announcement by Ethiopian Electric Power (EEP), QRB Labs, the only Ethiopian-founded Bitcoin mining company, issued a statement cautioning of severe adverse consequences for the sector.

The company, which officially received its license in 2021 and began operations three years later, states that the proposed pricing structure would substantially reduce the industry's competitiveness.

Freadam Moges, the company's Data Center Operations Director, says large Bitcoin miners in Texas, the biggest region in the world for this industry, average around 2.8 cents/kWh.

“Given that other costs of doing business are extremely high, this will eliminate Ethiopia as a destination for Bitcoin miners,” he told Shega.

QRB Labs estimates that half of Ethiopia’s Bitcoin operations could become unprofitable by mid-2026, rising to over 90% by 2027. The company warns this could slash EEP’s annual electricity revenues by $100 million by late 2026 and over $300 million by 2027.

The impact on QRB Labs itself could be severe.

“QRB Labs provides hosting services for international customers. We have no choice but to pass the increased costs on to them,” the director said. “Many will be forced to stop running their machines in the country. Revenues will decline, and it will be almost impossible to recover the initial capital investment, let alone make a profit.” Freadam noted.

He also pointed to another challenge that has long strained their operations related to payments.

“As an Ethiopian company, QRB Labs earns all its revenue in foreign currency. However, central bank regulations require banks to automatically convert 50% of that income into Birr, while Information Network Security Administration regulations mandate that we pay for electricity in U.S. dollars.”

“Electricity currently consumes about 60% of our revenue,” Freadam explained. “That means we constantly have to convert another 10% from Birr back into dollars at high cost, with long delays and a lot of uncertainty. With the new tariffs, electricity expenses will exceed 80% of revenue, making this double conversion process nearly impossible.

Though EEP’s latest notice may have seemed abrupt to many, it followed several earlier signs that foreshadowed a major policy overhaul.

In June 2025, the Ethiopian Investment Commission (EIC), led by Commissioner Zeleke Temesgen (PhD), announced a halt to the issuance of new Bitcoin mining licenses during an EU Chamber CEO meeting. A month later, EEP said it would no longer approve new power deals for crypto operations, citing the need to prioritize domestic electricity access.

However, just a few weeks later, the then State Minister of Finance (now National Bank Governor) Eyob Tekalign (PhD) attempted to allay concerns. Speaking on local private media, he reassured listeners that Bitcoin miners remain welcome in Ethiopia as long as they utilize stranded energy sources that would otherwise go unused. He clarified that while mining licenses would not be entirely suspended, the scale of new Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) would likely be reduced.

Even now, EEP portrays Bitcoin mining as strategic. Their communications director Moges Mekonen said last week miners generated over $82 million in revenue in the past three months, exceeding projections on state media. In the last fiscal year, EEP reported earning a total of $220 million from electricity sales to Bitcoin mining operations, while electricity exports generated just about $118 million. CEO Ashebir Balcha had said Bitcoin mining was not in their long-term strategy despite record revenues.

Bitcoin mining is an energy-intensive activity. Because the network uses a proof-of-work consensus system, miners around the world must run enormous numbers of specialized computing rigs continuously to solve complex cryptographic puzzles and secure the ledger, driving very high electricity consumption.

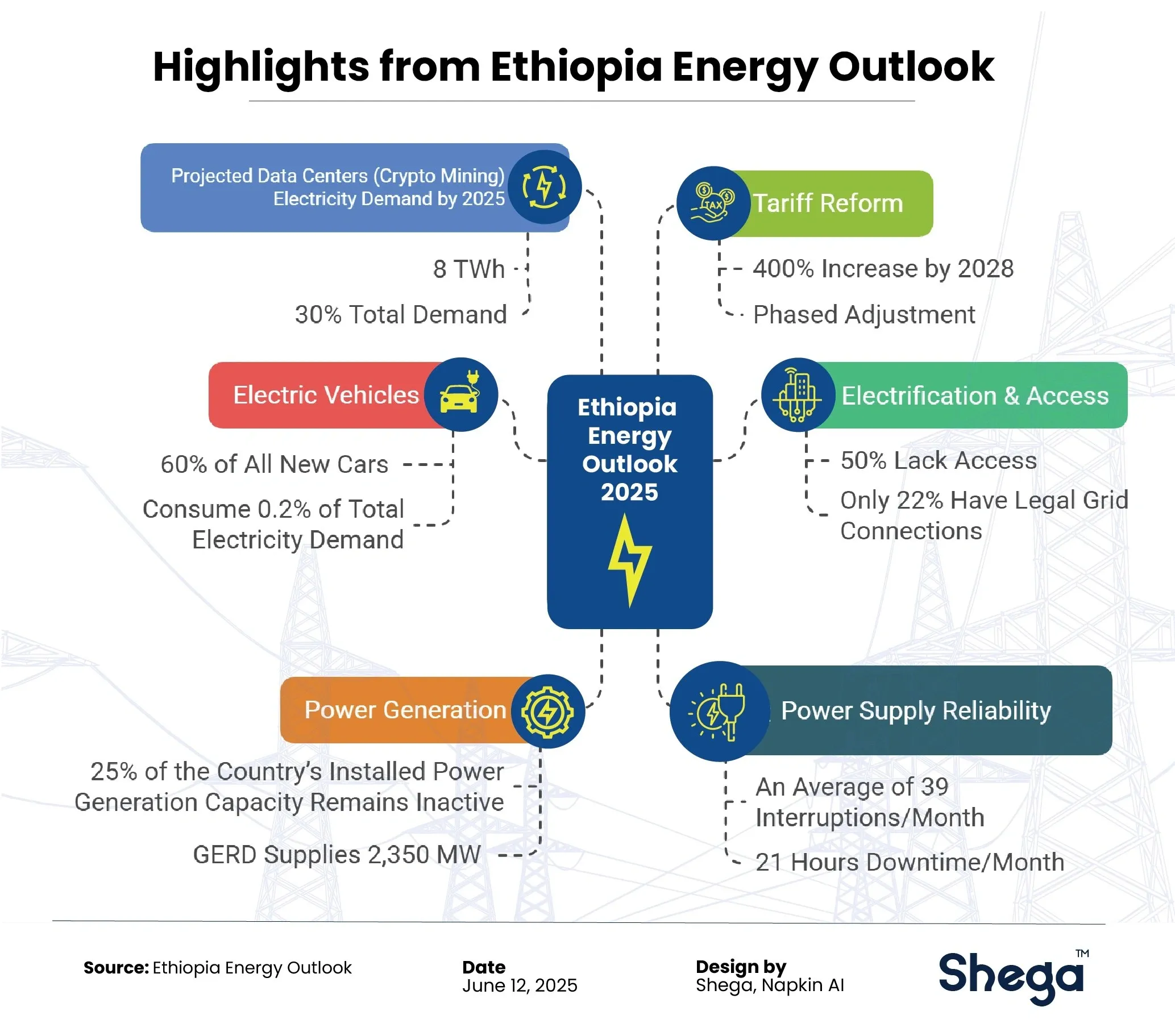

According to the Second Ethiopia Energy Outlook, a document co-authored by several government institutions, projected that about 30% national electricity demand would be from Bitcoin and data-mining operations, a significant surge for a country in which half the population doesn’t have access.

The conversation in Ethiopia isn’t just about how much power is used, but how it’s deployed, a distinction Bitcoin mining advocates highlight, noting their operations turn idle electricity into hard currency without burdening households.

Some reports bolster this claim, estimating that up to 30% of energy in the grid remains stranded. However, hardline critics have argued that since miners create few jobs, their impact on the grid outweighs their contribution to national foreign currency earnings.

For energy policy analysts like Yonas Ayele, availing of unused electricity during periods of low demand to miners paying a premium could bring about some much-needed good. He pins the viability of such an arrangement on whether the funds are channeled towards expanding electricity access to the millions of Ethiopians without it.

“The real issue is accountability and follow-up,” Yonas told Shega.

He explained that stranded energy is created when excess power is generated more than is transmittable through the existing grid or whenever demand falls below what is already moving in the grid. Yonas sees the new tariff rollout as a means of incentivizing miners to use energy in periods of off-peak hours to reduce strains on the grid.

Still, EEP’s new tariffs also introduce an availability-based tariff, which appears to penalize inconsistency and push for stable demand. Some industry insiders have perceived the policy pivot as a broader disavowal of bitcoin mining. An all too familiar story for many Bitcoin miners.

As Bitcoin mining's energy appetite collided with overstretched power grids, a wave of countries has cracked down on the industry. Kuwait enforced an absolute ban on all crypto mining in May 2025, seizing rigs blamed for fueling widespread blackouts during scorching summer peaks. Iran ramped up raids and seasonal shutdowns throughout 2025, as unlicensed operations exacerbated chronic shortages amid sanctions-hit infrastructure, while Russia's 10 regions halted mining through 2031 to ease regional power deficits. Countries like Kazakhstan abruptly cracked down on Bitcoin mining three years ago, shutting down thousands of rigs and forcing miners to flee after a series of blackouts and regulatory pressure threatened the country’s power grid.

In the relentless churn of Bitcoin mining, where soaring hash rates propel the network's security to unprecedented peaks, topping 600 EH/s in 2025, electricity costs emerge as the pivotal fulcrum, devouring up to 90% of operational expenses and dictating whether miners thrive in low-cost havens like Texas or falter amid grid-straining surges elsewhere.

Ethiopia’s earlier appeal was clear: abundant renewable energy, low electricity costs, and a government welcoming foreign investment in crypto. In early 2025, investors from China and beyond flocked to explore permits and opportunities in the budding Bitcoin haven.

That momentum, however, has faltered as new tariffs stoked doubts among investors already wary of Ethiopia’s unpredictable policy landscape.

Bernardo Medina, a Venezuelan Bitcoin entrepreneur dislodged by his government’s crackdown two years ago, was among them. Earlier this year, he moved to Ethiopia and says he paid the $200,000 deposit required by the Ethiopian Investment Commission (EIC) for a 30 MW mining permit, yet never received approval. After waiting in vain, he relocated to the U.S. in search of “regulatory certainty”.

“The main issue was that EIC was not taking us seriously as investors,” Bernardo told Shega. Frustrated by the delays and lack of clarity, he moved his operations, while the $200,000 remains frozen in Ethiopia, according to him.

Bernardo’s experience echoes the unpredictability and politicized reputation that have long shadowed Bitcoin mining. In 2016, as Venezuela spiraled into hyperinflation, Bernardo faced a critical choice. With his ice-cream factory shutting down, a friend suggested he try Bitcoin mining using a 300 KVA idle transformer. Skeptical at first, he was surprised when his Bitmain Antminer S4 produced 0.3 BTC in 24 hours, then valued at roughly $300.

By 2019, he was managing a Bitcoin mining company with seven facilities across Venezuela, totaling nearly 30 megawatts of capacity. Four years later, the venture collapsed under a government crackdown: sites were raided, transformers seized, and personnel detained, highlighting the sector’s precarious and politically charged nature.

“Everything was gone in one day,” Bernardo recalled.

The regulatory tides have once more swayed unfavorably for Bitcoin investors like him, an ocean away from his original home.

Despite a longstanding prohibition on cryptocurrency trading and a complex regulatory environment, Ethiopia relaxed mining regulations a few years back. It allowed “high-performance computing” and “data mining” in 2022, categories under which Bitcoin mining is permitted. By early 2024, at least 21 Bitcoin mining firms had secured licenses to operate in Ethiopia, all except two of them Chinese. The surge drew global attention, with some crypto circles dubbing Ethiopia “the next Bitcoin mining haven.”

Throughout most of 2025, Ethiopia’s reputation continued to grow. Miners displaced from other countries or seeking cheaper electricity amid tightening regulations elsewhere scouted Ethiopia as a low-cost electricity refuge. Yet this opportunity exists amid structural tension. Electricity often exceeds 60% of operational costs, even as Ethiopia’s hydroelectric grid, including power from the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), offers significantly lower rates than traditional hubs.

Companies like BIT Mining, Phoenix Group, and Bitdeer moved quickly to establish operations, but not all entrants have followed through. Terahash, which announced a US$5 million facility earlier this year, has since muted its activities. BitCity, operating a 10 MW site, cited “siloed” government agencies and poor coordination among regulators as reasons for holding back, despite initial plans to expand to hundreds of megawatts.

These examples highlight a mixed picture: Ethiopia promises low-cost, renewable energy, yet a widening gap between policy rhetoric and regulatory execution unsettles investors. Firms from China to the Middle East and Latin America had been preparing projects or expansions, but the sudden tariff hike and halted permits have dampened optimism.

For many investors, the deeper issue is not the cost of electricity but the volatility of the rules that govern it. Ethiopia has swung between welcoming and wary, offering incentives one month and tightening controls the next. This inconsistency, conflicting signals from regulators, abrupt policy shifts, and slow, opaque approval processes, has become its own form of risk. As a result, companies that once viewed Ethiopia as a stable, renewable-energy outlier in a tightening global landscape now see a country struggling to decide what role Bitcoin mining should play in its economy. Until that uncertainty settles, the hesitation that began with a few might widen.

QRB Labs’ white paper, Ethiopia’s Electricity Pricing Strategy, proposes shifting from location-based pricing to real-time, market-driven tariffs. The roadmap aims to generate $3 billion annually by 2028 and support a tenfold expansion of electrification by 2050.

The four-phase plan emphasizes efficiency, sustainability, market balance, and transparency, moving from geographic pricing to capacity auctions and finally real-time markets integrated into the Eastern Africa Power Pool, with consumer subsidies to protect low-income households.

In this framework, Bitcoin mining is framed not as a drain but as a temporary bridge, absorbing surplus power, earning foreign exchange, and stabilizing the grid, provided pricing remains clear and sustainable. Whether Ethiopia can strike that balance will determine if its mining hub can survive.

“As global Bitcoin mining consolidates in jurisdictions with stable policy and predictable energy costs,” QRB labs warned, “Ethiopia’s brief emergence as an African mining hub now hangs in the balance. For an industry where margins are measured in tenths of a cent, the tariff hike may prove fatal.

👏

😂

❤️

😲

😠

Etenat Awol

Etenat holds a degree in Journalism and her master's in Public Relations. Previously, she served as a university lecturer and has five years of experience in communications, media, digital marketing, and consulting.

Your Email Address Will Not Be Published. Required Fields Are Marked *