Progress for 0 ad

Progress for 1 ad

Progress for 2 ad

Progress for 3 ad

Mussie Solomon

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Publishing a book has never been easy. In Ethiopia, the hurdles are especially steep: a limited number of publishing houses, an eroding reading culture, and a largely informal distribution ecosystem. For many writers, self-publishing is the only viable path to reach readers, but it often fails to recover even modest production costs.

The arrival of digital platforms once promised a solution. Formats like e-books and audiobooks offered new channels for authors to reach readers directly, cutting costs and bypassing traditional gatekeepers. But in recent years, the growing prevalence of digital piracy, particularly across social media and messaging apps like Telegram, has begun to undermine those gains, threatening the livelihoods of Ethiopia’s emerging literary class.

Natnael Dagnaw, author of the Wede Ras anthology and founder of the now-defunct Romanat Publishing, has seen the toll firsthand.

“It's not just the high cost of paper that's burdensome,” he told Shega. “Distribution, financial management, and dealing with publishers, these processes demoralize writers.”

Natnael believes a broader public awareness of authors' struggles could help disincentivize the widespread sharing of pirated books, which often circulate with no compensation to the creators.

Digital platforms at first offered a way for authors to increase their reach, minimize costs, and diversify their readership. For authors like Hiwot Emishaw, the shift to digital platforms has been both liberating and frustrating. With five books to her name, she has published three of them online, including audio formats, in partnership with Tuba Books.

She notes how publishing 1000 copies of a 250-page book now costs around 250k Birr following recent tax levies on paper.

“Publishing needs to evolve to address recent challenges in the industry,” Hiwot told Shega.

Known for her unique ability to depict everyday life with humor, the author believes digital tools provide emerging writers with affordable access to the market, eliminating the need to negotiate with multiple publishers. Hiwot has observed that authors with relationships inside the publishing industry have an easier time finding distributors, retailers, or publishers.

“An author is considered successful if they manage to sell 15,000 copies,” says Hiwot. “That is actually a small number considering population size.”

While she sees digital platforms as a powerful tool that can help struggling authors, she also identifies the dangers. Hiwot feels disheartened whenever she sees books being shared on platforms without the author's consent.

While platforms like AfroRead, Tuba Ethiopian Books, Semu Audiobooks, and Teraki have enabled writers to financially benefit from their work, obscure channels on Telegram often reach larger audiences despite sidelining the authors themselves.

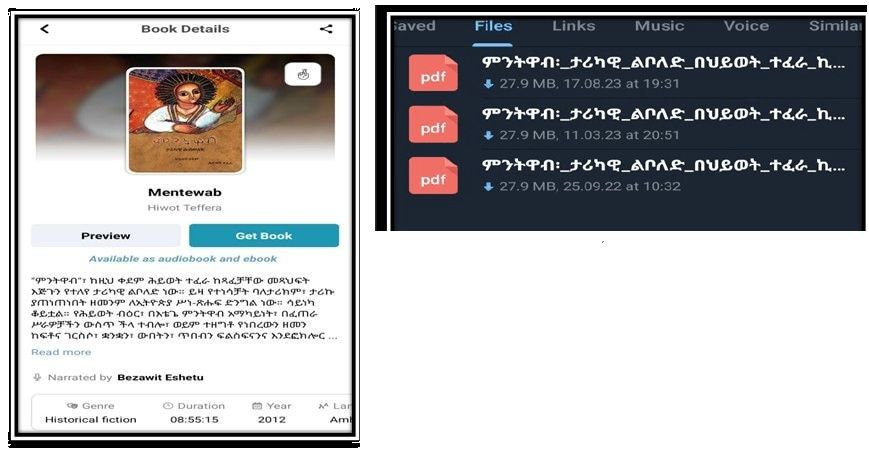

Most of these channels offer books in PDF and audio formats for free. Some take orders from subscribers who want a specific book converted into a digital format. They are strictly managed by admins who carefully curate the content with occasional groups spawning to order books.

Channels like Bihere Metsahift Ze-Ethiopia have over 100k subscribers while offering over thousands of PDFs, audios, and videos for free. Others such as Bete-Metsahift and Ke Metsahift Alem, have over 20k subscribers each, while dozens of similar channels on Telegram average around 2k subscribers.

An owner of such a Telegram channel with over 15k subscribers says she began sharing books online during the COVID-19 pandemic. She felt some older classic books were being sold at exorbitant prices and decided to do something about it. As subscribers grew, more requests started coming in, which meant more scanning and publishing.

“Although I don't profit from it, I find joy in knowing that people are benefiting from my efforts," she told Shega.

Since mostly old books are shared on her channel, she has not received harsh backlash from authors. However, she confirmed that some have shared concerns about their work being shared for free on similar channels.

"I am firmly opposed to sharing recent books,” she says.

Yet despite the rise of informal sharing, some local companies have found ways to protect intellectual property and build sustainable platforms.

The five-year-old Semu app has uploaded over 200 audiobooks and garnered over 40K loyal subscribers. Ruth Habtemariyam, production manager at Semu, says one of the main motives for establishing the app had to do with addressing unauthorized distribution. She notes how YouTube channels that share content for free end up harming both the authors and Semu.

"Whenever we publish an audiobook, we incur huge costs for narrators, editors, studio time, and other related expenses," Ruth laments.

Semu allows paying customers to download books for offline reading, gift them to other readers while rewarding those who invite friends onto the platform. Authors enter into an agreement that enables them to be compensated based on sales while the platform safeguards their work with tools like DRM encryption.

Platforms like Tuba Books, which has 200k downloads combined on Play Store and the App Store, have also resorted to encryption to prevent piracy. When users buy a book, it is stored within the app in an encrypted format. Leykun Yilma, Co-founder of the four-year-old company, says most people are unaware that sharing books without the author’s consent has legal implications.

“They think they are helping the authors gain recognition,” he told Shega.

Tuba allows authors to track the number of purchases of their work through a unique link, with the books being uploaded only after an agreement has been reached. Users can also look at ratings and book reviews by other readers before making a purchase.

For Ethiopian users, Tuba supports payment options through telebirr and the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia, while international customers can pay using Visa, MasterCard, or PayPal.

Leykun explained that they are combating the unauthorized sharing of books by providing a better user experience focused on affordability and accessibility, while also raising awareness about the importance of respecting intellectual property rights.

Internationally, there is no universal international copyright law that automatically safeguards one’s work worldwide. Instead, international copyright protection is established through a network of treaties and agreements. Copyright law is inherently territorial, meaning each country has its own domestic laws that govern the rights of its citizens and the use of foreign content within its borders.

Numerous pirate platforms are operating internationally, with Z Library being the most notable and has over 10 million books and more than 80 million articles. Despite efforts by the US government to shut down its website, Z Library continues to operate using different website addresses.

Locally, the Ethiopian Intellectual Property Office (EIPO) is responsible for managing issues related to Intellectual Property Rights (IPR). While the country has a legal framework in place to protect intellectual property rights, it has not yet implemented several key IPR treaties.

The Copyright and Neighboring Rights Protection Proclamation No. 410/2004 (commonly referred to as the copyright proclamation), which was amended a decade later, remains as the most formidable legal instrument.

Kaleegziyabher Gossaye, a lawyer and legal advisor who specializes in intellectual property rights at Ethio-Alliance Advocate LLP, states that distributing books via Telegram and websites is without the consent of the authors is illegal. He explains that Ethiopian law offers authors protection, outlines how their work can be used, and provides enforcement measures in cases where their rights are violated.

“Ethiopian law prohibits copying and distributing an author's work on social media, whether for commercial or non-commercial purposes, without the author's consent. Such actions are considered criminal offenses and are also subject to civil penalties. This includes compensation for moral/civil damages starting at 100,000 Birr, as well as any economic losses incurred due to unauthorized distribution,” Kaleegziyabher told Shega.

However, the ineffective implementation of these laws is compromising the rights of authors and those entitled to distribute artistic works. Kaleegziyabher says that this partly emanates from the law itself.

“Ethiopian law lacks clarity regarding its emphasis, whether it prioritizes the integrity of authors' rights or treats the work as a commodity,” he explains.

👏

😂

❤️

😲

😠

Mussie Solomon

Mussie Solomon is an intern at Shega Media and a first-year graduate degree student at the Institute for Peace and Security Studies. He is passionate about startups, technology, and digital finance.

Your Email Address Will Not Be Published. Required Fields Are Marked *